By John J. Mearsheimer*

The following are extensive excerpts from the article issued by The Transnational, which republished it from Mearsheimer’s Substack page on 5 August 2024.

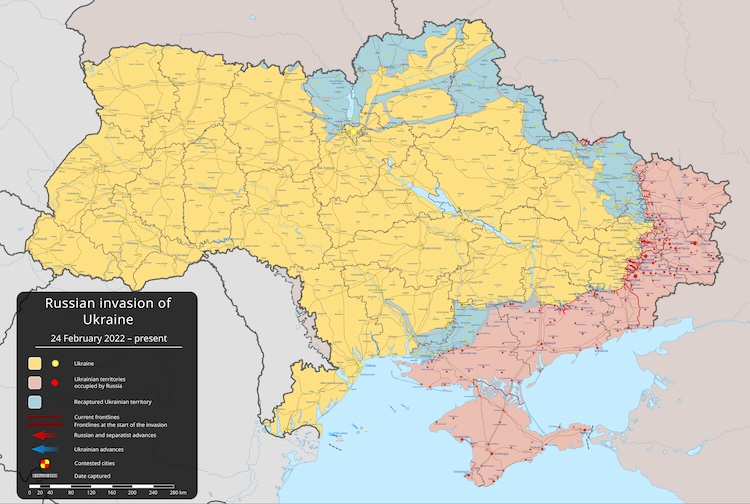

CHICAGO, USA | 7 August 2024 (IDN) — The question of who is responsible for causing the Ukraine war has been a deeply contentious issue since Russia invaded Ukraine on 24 February 2022. The conventional wisdom in the West is that Vladimir Putin is responsible for causing the Ukraine war.

The invasion aimed at conquering all of Ukraine and making it part of a greater Russia, so the argument goes. Once that goal was achieved, the Russians would move to create an empire in Eastern Europe, much like the Soviet Union did after World War II. Thus, Putin is ultimately a threat to the West and must be dealt with forcefully. In short, Putin is an imperialist with a master plan who fits neatly into a rich Russian tradition.

UC Political Science Website Photo. Credit: Joe Sterbenc

The alternative argument, which I identify with, and which is clearly the minority view in the West, is that the United States and its allies provoked the war.

This is not to deny, of course, that Russia invaded Ukraine and started the war. But the principal cause of the conflict is the NATO decision to bring Ukraine into the alliance, which virtually all Russian leaders see as an existential threat that must be eliminated.

NATO expansion, however, is part of a broader strategy that is designed to make Ukraine a Western bulwark on Russia’s border. Bringing Kyiv into the European Union (EU) and promoting a color revolution in Ukraine—turning it into pro-Western liberal democracy—are the other two prongs of the policy. Russia leaders fear all three prongs, but they fear NATO expansion the most. To deal with this threat, Russia launched a preventive war on 24 February 2022.

The debate about who caused the Ukraine war recently heated up when two prominent Western leaders—former President Donald Trump and prominent British MP Nigel Farage—made the argument that NATO expansion was the driving force behind the conflict.

Unsurprisingly, their comments were met with a ferocious counterattack from defenders of the conventional wisdom. It is also worth noting that the outgoing Secretary General of NATO, Jens Stoltenberg, said twice over the past year that “President Putin started this war because he wanted to close NATO’s door and deny Ukraine the right to choose its own path.” Hardly anyone in the West challenged this remarkable admission by NATO’s head and he did not retract it.

My aim here is to provide a primer, which lays out the key points that support the view that Putin invaded Ukraine not because he was an imperialist bent on making Ukraine part of a greater Russia, but mainly because of NATO expansion and the West’s efforts to make Ukraine a Western stronghold on Russia’s border.

Let me start with the SEVEN MAIN REASONS to reject the conventional wisdom.

FIRST, there is simply no evidence from before 24 February 2022 that Putin wanted to conquer Ukraine and incorporate it into Russia. Proponents of the conventional wisdom cannot point to anything Putin wrote or said that indicates he was bent on conquering Ukraine.

When challenged on this point, purveyors of the conventional wisdom provide evidence that has little if any bearing on Putin’s motives for invading Ukraine. For example, some emphasize that he said Ukraine is an “artificial state“ or not a “real state.” Such opaque comments, however, say nothing about his reason for going to war.

The same is true of Putin’s statement that he views Russians and Ukrainians as “one people“ with a common history. Others point out that he called the collapse of the Soviet Union “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century.” But Putin also said, “Whoever does not miss the Soviet Union has no heart. Whoever wants it back has no brain.”

Still, others point to a speech in which he declared that “Modern Ukraine was entirely created by Russia or, to be more precise, by Bolshevik, Communist Russia.” But that hardly constitutes evidence that he was interested in conquering Ukraine. Moreover, he said in that same speech: “Of course, we cannot change past events, but we must at least admit them openly and honestly.”

To make the case that Putin was bent on conquering all of Ukraine and incorporating it into Russia, it is necessary to provide evidence that 1) he thought it was a desirable goal, 2) he thought it was a feasible goal, and 3) he intended to pursue that goal. There is no evidence in the public record that Putin was contemplating, much less intending to put an end to Ukraine as an independent state and make it part of greater Russia when he sent his troops into Ukraine on 24 February 2022.

In fact, there is significant evidence that Putin recognized Ukraine as an independent country.

In his well-known 12 July 2021 article dealing with Russian-Ukrainian relations, which proponents of the conventional wisdom often point to as evidence of his imperial ambitions, he tells the Ukrainian people, “You want to establish a state of your own: you are welcome!”

Regarding how Russia should treat Ukraine, he writes, “There is only one answer: with respect.” He concludes that lengthy article with the following words: “And what Ukraine will be—it is up to its citizens to decide.” These statements are directly at odds with the claim that Putin wanted to incorporate Ukraine within a greater Russia.

In that same 12 July 2021 article and again in an important speech he gave on 21 February 2022, Putin emphasized that Russia accepts “the new geopolitical reality that took shape after the dissolution of the USSR.” He reiterated that same point for a third time on 24 February 2022, when he announced that Russia would invade Ukraine.

In particular, he declared that “It is not our plan to occupy Ukrainian territory” and made it clear that he respected Ukrainian sovereignty, although only up to a point: “Russia cannot feel safe, develop, and exist while facing a permanent threat from the territory of today’s Ukraine.”

In essence, Putin was not interested in making Ukraine a part of Russia; he was interested in making sure it did not become a “springboard“ for Western aggression against Russia.

SECOND, there is no evidence that Putin was preparing a puppet government for Ukraine, cultivating pro-Russian leaders in Kyiv, or pursuing any political measures that would make it possible to occupy the entire country and eventually integrate it into Russia.

Those facts fly in the face of the claim that Putin was interested in erasing Ukraine from the map.

THIRD, Putin did not have anywhere near enough troops to conquer Ukraine.

Let’s start with the overall numbers. I have long estimated that the Russians invaded Ukraine with at most 190,000 troops. General Oleksandr Syrskyi, the present commander-in-chief of Ukraine’s armed forces, recently said in an interview with The Guardian that Russia’s invasion force was only 100,000 strong. Indeed, The Guardian used that same number before the war started. There is no way that a force of either 100,000 or 190,000 could conquer, occupy, and absorb all of Ukraine into a greater Russia.

Consider that when Germany invaded the western half of Poland in September 1939, the Wehrmacht numbered about 1.5 million men.

Ukraine is geographically more than 3 times larger than the western half of Poland was in 1939 and Ukraine in 2022 had almost twice as many people as Poland did when the German invaded.

If we accept General Syrskyi’s estimate that 100,000 Russian troops invaded Ukraine in 2022, that means Russia had an invasion force that was 1/15th the size of the German force that went into Poland. And that small Russian army was invading a country that was much larger than Poland in terms of both territorial size and population.

Numbers aside, there is the matter of the quality of the Russian army.

For starters, it was a military force largely designed to defend Russia from invasion. It was not an army primed to launch a major offensive that would end up conquering all of Ukraine, much less threatening the rest of Europe.

Furthermore, the quality of the fighting forces left much to be desired, as the Russians were not expecting a war when the crisis began to heat up in the spring of 2021.

Thus, they had little opportunity to train-up a skilled invasion force. In terms of both quality and quantity, the Russian invasion force was not close to being the equivalent of the Wehrmacht in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

One might argue that Russians leaders thought that the Ukrainian military was so small and so outgunned that their army could easily defeat Ukraine’s forces and conquer the entire country.

In fact, Putin and his lieutenants were well-aware that the United States and its European allies had been arming and training the Ukrainian military since the crisis first broke out on 22 February 2014.

Moscow’s great fear was that Ukraine was becoming a defacto member of NATO. Moreover, Russian leaders observed the Ukrainian army, which was larger than their invasion force, fighting effectively in the Donbass between 2014 and 2022. They surely understood that the Ukrainian military was not a paper tiger that could be defeated quickly and decisively, especially since it had powerful backing from the West.

Finally, over the course of 2022, the Russians were forced to withdraw their army from the Kharkiv oblast and from the western part of the Kherson oblast. In effect, Moscow surrendered territory that its army had conquered in the opening days of the war. There is no question that pressure from the Ukrainian army played a role in forcing the Russian withdrawal.

But more importantly, Putin and his generals realized that they did not have sufficient forces to hold all the territory their army had conquered in Kharkiv and Kherson. So, they retreated and created more manageable defensive positions. This is hardly the behavior one would expect from an army that was built and trained to conquer and occupy all of Ukraine. Of course, it was not designed for that purpose and thus could not achieve that Herculean task.

FOURTH, in the months before the war started, Putin tried to find a diplomatic solution to the brewing crisis.

On 17 December 2021, Putin sent a letter to both President Joe Biden and NATO chief Stoltenberg proposing a solution to the crisis based on a written guarantee that: 1) Ukraine would not join NATO, 2) no offensive weapons would be stationed near Russia’s borders, and 3) NATO troops and equipment moved into eastern Europe since 1997 would be moved back to western Europe. Whatever one thinks of the feasibility of reaching a bargain based on Putin’s opening demands, which the United States refused to negotiate over, it shows that he was trying to avoid war.

FIFTH, immediately after the war began, Russia reached out to Ukraine to start negotiations to end the war and work out a modus vivendi between the two countries.

Negotiations between Kyiv and Moscow began in Belarus just four days after Russian troops entered Ukraine. That Belarus track was eventually replaced by an Israeli as well as an Istanbul track.

All the available evidence indicates that the Russia was negotiating seriously and was not interested in absorbing Ukrainian territory, save for Crimea, which they had annexed in 2014, and possibly the Donbass. The negotiations ended when the Ukrainians, with prodding from Britain and the United States, walked away from the negotiations, which were making good progress when they ended.

Furthermore, Putin reports that when the negotiations were taking place and making progress, he was asked to remove Russian troops from the area around Kyiv as a good will gesture, which he did on 29 March 2022 . No government in the West or former policymaker has challenged Putin’s claim, which is directly at odds with the claim that he was bent on conquering all of Ukraine.

SIXTH, putting Ukraine aside, there is not a scintilla of evidence that Putin was contemplating conquering any other countries in eastern Europe.

Moreover, the Russian army is not even large enough to overrun all of Ukraine, much less try to conquer the Baltic states, Poland, and Romania. Plus, all those countries are NATO members, which would almost certainly mean war with the United States and its allies.

SEVENTH, hardly anyone in the West argued that Putin had imperial ambitions from the time he took the reins of power in 2000 until the Ukraine crisis started on 22 February 2014. At that point, he suddenly became an imperial aggressor. Why? Because Western leaders needed a reason to blame him for causing the crisis.

Source: Georgia Today

Probably the best evidence that Putin was not seen as a serious threat during his first fourteen years in office is that he was an invited guest at the April 2008 NATO summit in Bucharest, which is where the alliance announced that Ukraine and Georgia would eventually become members.

Putin, of course, was enraged by that decision and made his anger known. But his opposition to that announcement had hardly any effect on Washington because Russia’s military was judged to be too weak to stop further NATO enlargement, just as it had been too weak to stop the 1999 and 2004 waves of expansion. The West thought it could once again shove NATO expansion down Russia’s throat.

Relatedly, NATO enlargement before 22 February 2014 was not aimed at containing Russia. Given the sad state of Russian military power, Moscow was in no position to conquer Ukraine, much less pursue revanchist policies in eastern Europe.

Tellingly, former US ambassador to Moscow Michael McFaul, who is a staunch defender of Ukraine and scathing critic of Putin, notes that Russia’s seizure of Crimea in 2014 was not planned before the crisis broke out; it was an impulsive move in response to the coup that overthrew Ukraine’s pro-Russian leader. In short, NATO expansion was not intended to contain a Russian threat, because the West did not think there was one.

It was only when the Ukraine crisis erupted in February 2014 that the United States and its allies suddenly began describing Putin as a dangerous leader with imperial ambitions and Russia as a serious military threat that NATO had to contain.

Abrupt shift in rhetoric to enable the West to blame Putin

This abrupt shift in rhetoric was designed to serve one essential purpose: to enable the West to blame Putin for the crisis and absolve the West of responsibility. Unsurprisingly, that portrayal of Putin gained much greater traction after Russia invaded Ukraine on 24 February 2022.

There is one twist on the conventional wisdom that bears mentioning. Some argue that Moscow’s decision to invade Ukraine has little to do with Putin himself and instead is part of an expansionist tradition that long predates Putin and is deeply wired into Russian society. This penchant for aggression, which is said to be driven by internal forces, not Russia’s external threat environment, has driven virtually all Russian leaders over time to behave violently toward their neighbors. There is no denying that Putin is in charge in this story or that he led Russia to war, but he is said to have little agency. Almost any other Russian leader would have acted the same way.

There are two problems with this argument. For starters, it is non-falsifiable, as the longstanding trait in Russian society that produces this aggressive impulse is never identified. Russians are said to have always been aggressive—no matter who is in charge—and always will be.

It is almost as if it were in their DNA. This same claim was once made about Germans, who were often portrayed during the twentieth century as congenital aggressors. Arguments of this sort are not taken seriously in the academic world for good reason.

Furthermore, hardly anyone in the United States or Western Europe characterized Russia as innately aggressive between 1991 and 2014, when the Ukraine crisis broke out. Outside of Poland and the Baltic states, fear of Russian aggression was not a concern frequently voiced during those twenty-four years, which one would expect if the Russians were wired for aggression. It seems clear that the sudden appearance of this line of argument was a convenient excuse to blame Russia for causing the Ukraine war.

*John J. Mearsheimer is the R. Wendell Harrison Distinguished Service Professor of Political Science at the University of Chicago, where he has taught since 1982. He graduated from West Point in 1970 and then served five years as an officer in the U.S. Air Force. He then started graduate school in political science at Cornell University in 1975. He received his PhD in 1980. He spent the 1979-1980 academic year as a research fellow at the Brookings Institution, and was a post-doctoral fellow at Harvard University’s Center for International Affairs from 1980 to 1982. During the 1998-1999 academic year, he was the Whitney H. Shepardson Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York. [IDN-InDepthNews]

Image credit: The Transnational