By Jonathan Power

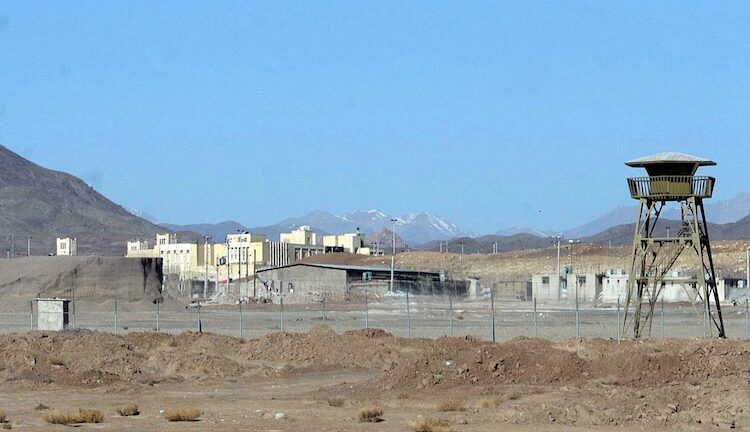

LUND, Sweden | 10 February 2026 (IDN) — We are heading toward a potential collision between President Donald Trump and international law. Anyone listening carefully to his rhetoric about Iran and its alleged nuclear weapons programme can sense it coming.

Trump has spoken in tones I would describe as “fire and brimstone.” That is hardly the language of the United Nations Charter, which begins with the measured words:

“We the peoples of the United Nations, determined to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war… and to establish conditions under which justice and respect for the obligations arising from treaties and other sources of international law can be maintained… and for these ends to practice tolerance and live together in peace with one another as good neighbours.”

There is a vast distance between those founding aspirations and the language of preemption and threat.

Under the UN Charter, the use of force is tightly constrained. A state may not launch a pre-emptive strike — nuclear or conventional — unless war is imminent in a clearly demonstrable way. The doctrine of self-defence is permitted only if there is an actual or impending armed attack. Imminence must be visible: unmistakable troop mobilisations, concrete preparations for assault, movements that leave no doubt about hostile intent.

Iran is not engaged in such actions.

The Charter’s Article 51 allows self-defence only “if an armed attack occurs.” It does not grant a blank cheque for preventive war — the striking of a potential rival before it becomes dangerous.

For his part, President Trump should also refrain from actions that inflame tensions and make Iran believe the United States is rehearsing for a strike. Military exercises close to another state’s borders are not confidence-building measures. They are the opposite. They do not reflect what the Charter calls “effective measures for the prevention and removal of threats to peace.”

The language of intimidation rarely produces compliance. More often, it produces defiance.

The Limits of Pre-Emptive War

Up until the late nineteenth century, states claimed a customary right to go to war whenever they deemed it necessary. Political leaders justified armed conflict for unpaid debts, territorial ambition, dynastic quarrels, colonial “civilising” missions, or wounded honour.

War was justified politically, not legally.

The twentieth century sought to change that. After two world wars, the UN Charter attempted to outlaw aggressive war altogether. Armed force would be legitimate only in self-defence or when authorised by the Security Council.

Today, few openly defend the old doctrine of discretionary war. Even powerful states feel compelled to cloak military action in legal reasoning. The language of “self-defence” has become the universal justification.

But this is precisely where danger lies.

The elasticity of “self-defence” has been stretched repeatedly. Leaders have learned how to shape facts and narratives to fit the legal mould.

How Leaders Bend the Law

The United States persuaded the UN Security Council to authorise force against Iraq in 1990 after Saddam Hussein seized Kuwait. President George H.W. Bush understood that legality mattered. International backing conferred legitimacy.

Twelve years later, his son, George W. Bush, took a different course. On the eve of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, he refused to wait for UN weapons inspector Hans Blix to complete his work. The claim that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction was presented as urgent and undeniable.

It was neither.

When no such weapons were found, there was no formal admission of wrongdoing. Years later, Tony Blair offered something close to regret — but the damage had been done.

The pattern repeated elsewhere. The UN Convention Against Torture — ratified under conservative governments in Washington and London — was not repudiated by Bush or Blair. Instead, it was linguistically reshaped. Waterboarding and similar practices were labelled “enhanced interrogation.” Torture was redefined to avoid the legal prohibition.

The words changed. The practice did not.

Later, both George W. Bush and Barack Obama extended the “self-defence” argument to targeted drone strikes against suspected terrorists. Yet the Charter is clear: emergency self-defence applies only before the Security Council can act. Once the Council determines that aggression exists, it may authorise a collective response.

Iran is not creating such an emergency. There are no missiles in flight. No columns of armour rolling across borders.

The American legal scholar Ian Hurd, in his incisive book How to Do Things With International Law, observes that broad interpretations of self-defence can make “the ban on war look more like an authorization of the use of force than a constraint upon it.”

That is a devastating sentence.

Hurd notes that such interpretations have evolved “under the influence of strong states.” Yet he also reminds us that the Charter still carries moral and political weight. Even powerful nations hesitate to discard it openly. They seek instead to reinterpret it.

That hesitation matters. It means the norm still exists.

A Pattern of Erosion

President Bill Clinton bypassed the Security Council when NATO intervened in Yugoslavia and later Kosovo. The humanitarian motive — to halt ethnic cleansing — was widely cited. But legality was stretched.

President Vladimir Putin’s annexation of Crimea and invasion of Ukraine ignored the Charter outright.

Each episode chips away at the post-1945 legal order.

The Charter’s core promise was that aggression would no longer be acceptable — not for profit, not for ideology, not for the defence of democracy, and not for “civilising missions.”

And yet, repeatedly, leaders convince themselves that exceptional circumstances justify exceptional measures.

A Test for the UN System

If President Trump were to authorise a preventive strike against Iran without clear evidence of imminent attack, he would place himself squarely in this lineage of legal distortion.

Such a strike would not simply be a military action. It would be a test of whether the post-1945 international order still constrains the strong.

International law is imperfect. It lacks a world police force. It relies on consent, pressure, and legitimacy. But it has changed its behaviour over time. Open declarations of aggressive war are now rare. Even autocrats feel the need to justify their actions in legal terms.

The Charter’s language still shapes global discourse.

What is at stake with Iran is more than regional stability. It is whether the world continues to accept that armed force must be restrained by law.

If the principle of self-defence is broadened to include hypothetical future threats, then every state with a grievance could justify preventive war. The prohibition on aggression would dissolve into a matter of interpretation.

That would return us to the nineteenth century.

The Stakes of Escalation

There is also a practical dimension. Military action against Iran would almost certainly trigger retaliation — directly or through regional proxies. Oil markets would convulse. Diplomacy would collapse. Civilian populations would suffer.

The Charter was written not as abstract idealism but as a hard-earned lesson. The drafters had seen two world wars. They knew that once unleashed, war rarely remains contained.

Trump’s rhetoric may thrill certain domestic audiences. It may be intended as leverage. But threats have a habit of hardening into expectations.

States that feel encircled or targeted rarely capitulate quietly. They prepare.

Law as Stability

Bush, Blair, Clinton, Obama, and Putin each, in different ways, stretched or ignored the Charter’s constraints.

They were wrong.

International law is not an academic nicety. It is a framework that reduces unpredictability. It establishes boundaries that even powerful states are expected to respect.

When leaders treat it as flexible clay, the structure weakens.

The tragedy is not only that wars occur. It is that each breach normalises the next.

The Hardest Knock?

It is increasingly evident that President Trump may be prepared to subject international law to its most severe test yet.

The world does not need another preventive war justified by expansive readings of “self-defence.” It needs restraint, verification, negotiation, and patient diplomacy.

The UN Charter does not forbid strength. It forbids aggression.

Whether Washington chooses to honour that distinction will determine not only the fate of Iran, but the credibility of the international legal order itself. [IDN-InDepthNews]

Copyright: Jonathan Power.