By A. L. A. Azeez*

COLOMBO 8 July 2023 (IDN) — Discussions on the Indian Ocean regional order and Indo-Pacific—and on China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—involve strategic interests and aspirations of countries in the region and beyond.

Given that the Indian Ocean is traversed annually by almost 100,000 commercial ships and that over 80% of the world’s oil is transported by sea, it is clear that these sea lanes are among the most important in the entire globe.

Sri Lanka located just South of India, and at the heart of the Indian Ocean, obviously has critical interests.

This, in turn, calls for sustained engagement; a cogent multilateral vision; and an internally inclusive evolution of coherent policies and positions. Equally important is the language and how the country engages with external interlocutors.

Among remarks the National Security Advisor and Sri Lanka President’s Chief of Staff made at the Shangri-la Dialogue on 2-3 June 2023 in Singapore one is of particular significance. It relates to Sri Lanka’s Foreign Policy and multilateral diplomacy.

He pointed out that Sri Lanka would be assuming the chair of the Indian Ocean Regional Association (IORA) later this year, and suggested IORA “an obvious choice for initiating discussions and related action at a politically high level”. He also touched on the roles of ASEAN, seven South Asian and Southeast Asian Nations (BIMSTEC); and the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF).

What would be these discussions about and what the action that National Security adviser has on mind? In his view it should be to “evolve a security and economic architecture for the Indian Ocean region”.

Leaving aside the “economic” part of the envisaged arrangement, it is pertinent to note that the term “architecture” in today’s world is used more in relation to security or defence.

A region’s common framework, agreements, institutions, and processes for managing and addressing security issues and threats are referred to as regional security architecture.

It is a collaborative strategy, built upon a shared vision, that seeks to strengthen regional stability, advance peace, and encourage cooperation among member states. It can exist in varied shades and shapes. NATO is the most advanced with its collective defence orientation.

Contextually, the remarks made at Shangri-la—organised by the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS)—imply that ARF, ASEAN, BIMSTEC and IORA are all important when it comes to the question of putting in place a regional security arrangement. The security adviser apparently believes discussions—and “related action” on the issue of evolving a security architecture—can be initiated at a politically high level within IORA.

A caution, however, is in order on this point.

The nature and scope of IORA is not security oriented. It is centred on economic cooperation and on achieving sustained growth and balanced development in the region. Economic cooperation extends to areas of trade facilitation and liberalisation, promotion of foreign investment, scientific and technological exchanges, tourism, and movement of natural persons and service providers.

Sustained growth and balanced development are sought to be realised through the development of infrastructure and human resources. It includes the promotion of maritime transport and related matters, cooperation in the fields of fisheries trade, research and management, aquaculture, education and training, energy, IT, health, protection of the environment, agriculture, disaster management and poverty alleviation.

Connectivity and communication, climate action, ocean and marine resources development and other aspects of the UN Development Agenda-2030 are addresses as part of economic cooperation.

Emphasising “the unique geo-strategic primacy” of the region, in 2011 the agreed areas of cooperation were prioritised for inclusion in a “dynamic road map”, and the importance of cooperation in ‘maritime safety and security’ was reiterated.

Hence, discussions within IORA on maritime safety and security issues are a part of its broader mandate, a mandate which is essentially and preponderantly rooted in regional economic cooperation. Challenges addressed in this context include transnational crimes such as trafficking-in of arms and drugs as well as piracy and terrorism.

Maritime safety and security, it is obvious, is only a part of what the notion of ‘regional security’—in this instance ‘Indian Ocean regional security’—entails. The distinction between the constructs of ‘Indian Ocean’ and ‘Indian Ocean Region’, despite some using the terms interchangeably in “IR discourses”, is crucial in this regard.

Envisioning the IORA as an “obvious choice for discussions” on this matter may be a possibility. Indeed, in terms of Article 5 (a) (i) of the IORA Charter, the Council of Ministers may take “decisions on new areas of cooperation, establishment of additional mechanisms” and “other matters of general interest.”

The agreed objectives of IORA under Article 3 of its Charter, however, provide for addressing issues of maritime safety and security, but do not appear to extend to regional security as a whole. It is further circumscribed by Article 2 (d) which cautions that “bilateral and other issues likely to generate controversy and be an impediment to regional cooperation efforts will be excluded from deliberations.”

It follows therefore that at best IORA may be able to deliberate on issues of security concern that fall within the broader rubric of maritime safety and security, since it is already a part of its mandate. Discussion of any other issues that ordinarily form the broader picture of regional security will, within IORA, be contingent upon their being likely not controversial and not impediment to regional cooperation efforts.

The foundational principle, contained in Article 2 (c) of the Charter, which requires that decisions be made only on the basis of consensus, confirms this reality. Where one member of the IORA considers that a matter to be discussed is controversial or is an impediment to regional cooperation efforts, the principle of consensus effectively ensures there will be no room for deliberations at any level of the organisation.

Consensus is a principle of general applicability in any fora where it has been recognised as the basis for decision-making. The principle of non-controversiality, on the other hand, is one of preventive or restrictive nature which has the effect of putting a damper on free discussions.

In practical terms, it is a burden placed on smaller or less powerful members. A bigger or more powerful one can easily have a matter excluded from deliberations of IORA invoking this principle.

It is perhaps partly in acknowledgement of this constraint, that the Charter, in Article 5 (c), provides for a ministerial retreat. It is a platform usually available for a free and frank discussion of new ideas and new areas of collaboration.

In the case of IORA however, there is an implicit condition contained in that Charter provision, which ensures that only those matters that are agreed upon through prior consultations among member states, can be taken up at the ministerial retreat.

When the IORA approach to consultation and consensus is contrasted with the ASEAN way of deliberation, it is clear where IORA lags behind. In ASEAN all decisions are made following the principles of consensus and consultation. However, Article 20 of the ASEAN Charter provides that, where consensus cannot be achieved over a matter, the ASEAN Summit “may decide how a specific decision can be made” thereon.

What is ASEAN’s strength is unfortunately IORA’s limitation. The latter’s “politically high level”, which the NSA’s statement at Shangri-la refers to, is the Council of Ministers. There is no higher level within IORA to take a matter to, when that matter is either excluded from deliberations, or does not achieve consensus following deliberations.

All this appears to make IORA a more constrained fora for open and candid discussions than most organisations of a similar magnitude elsewhere. In this backdrop, the question arises as to how far it would be realistic to conceive IORA as a forum for “related action”, going beyond deliberations, on the matter of evolving an Indian Ocean security architecture. A corollary to the question is whether Sri Lanka would be able to push such a proposition through the IORA in the circumstances explained.

That said, it could be a different scenario altogether if the intention was to promote it within IORA at the bidding of a bigger or more powerful member state. That some of the smaller members are often used by a bigger one to advance, within a fora, what is in the national interest of the latter is diplomacy by proxy.

Notwithstanding this, our diplomatic history—barring, in particular, the period from 2010-2014 and since 2019—amply demonstrates that the nation has largely succeeded in making some of the imponderables into realities on multilateral fronts. Now clipped economically and with political capital eroded, it still has the ability to make diplomatic gains in any fora that matters to it most, provided there is a cogent multilateral vision, underpinned by inclusive, coherent policies and good communication.

It would therefore be prudent, without striking a pessimistic note, to make it a matter of challenge for Sri Lanka’s diplomacy and political leadership. It would be appropriate that they prove the viability of IORA being the forum for action, for evolving an Indian Ocean regional security architecture if that were the intention behind the statement made at Shangri-la.

Our recent record as a member of regional organisations or groups speaks for itself loudly, though.

When there was no consent from one member of the eight-nation South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) to the convening of the long-overdue SAARC summit, Sri Lanka went ahead issuing a separate press release that there was no unanimity on holding the next summit. Under Article 10 of the SAARC Charter, one member not giving consent is enough to deny unanimity to any proposal.

When a similar situation arose in the year 2000, both the Foreign Minister of Sri Lanka and the Sri Lankan Secretary General of SAARC played an active role in breaking the stalemate. They worked closely with Nepal whose turn it was to host the summit, and also with other countries. We have now left SAARC to rot.

When BIMSTEC was established 25 years ago, Sri Lanka projected it as a bridge between SAARC and ASEAN; sort of a corridor connecting South Asia to Southeast Asia. There was at least some broad thinking then, as to what BIMSTEC should be like in the future. But what is Sri Lanka’s vision of it now?

Despite statements extolling the virtues of BIMSTEC, the reality is that sustained institutional support and high-level attention given to it by Sri Lanka, especially on matters involving effective preparation, representation and follow-up, have slackened in recent years.

There is currently a lack of vision and leadership necessary for meaningful regional cooperation. No sustained efforts have been made to explore back-channel initiatives to resurrect the trade sector and to ensure that BIMSTEC advances in areas like trade facilitation.

In 2012 Sri Lanka hastened to accept the chairmanship of what was then a floundering group of 17 states, known as G-15. The decision was influenced by a desperate need to confer on Sri Lanka what the then President thought was a global leadership role. It was pointed out to the initiators of this idea, that there had been no momentum within the group and that it would only be disadvantageous for Sri Lanka to take over it, wasting public funds.

Nonetheless, this concern was dismissed, and it was asserted that Sri Lanka was assuming the chair in order to revitalise the group and to make it more relevant to the needs of the 21st century.

Five years from then on, ironically it was over the liquidation of G-15 that Sri Lanka had to preside.

All this might suggest that the ‘obvious choice’ theory is a rhetorical piece from Sri Lanka’s political and diplomatic playbook in active use since 2010. It may remain so unless it is proved otherwise. The innate strength of Sri Lanka’s diplomacy and political leadership will be put to the test on this score in the coming months.

*The author is former Permanent Representative of Sri Lanka to the UN in Geneva and is associated with IDN-InDepthNews, the flagship agency of the Berlin-based International Press Syndicate. [IDN-InDepthNews]

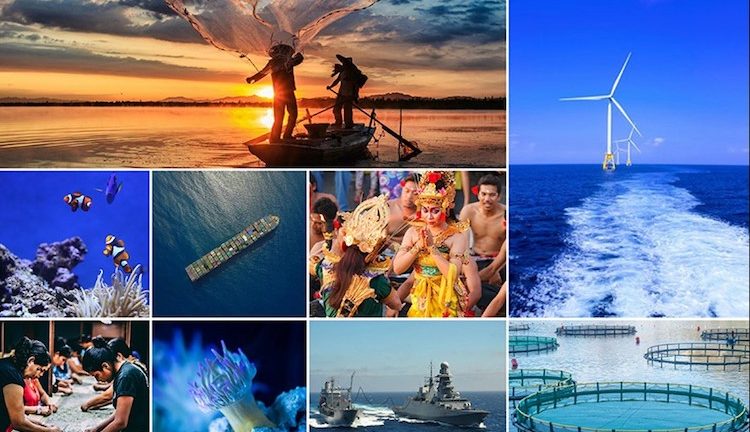

Image credit: IORA

We believe in the free flow of information. Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons Attributi