By Krishan Dutta

PARIS (IDN) – “Donor countries are not living up to their 2015 pledge to ramp up development finance and this bodes badly for us being able to achieve the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals,” OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurría has cautioned.

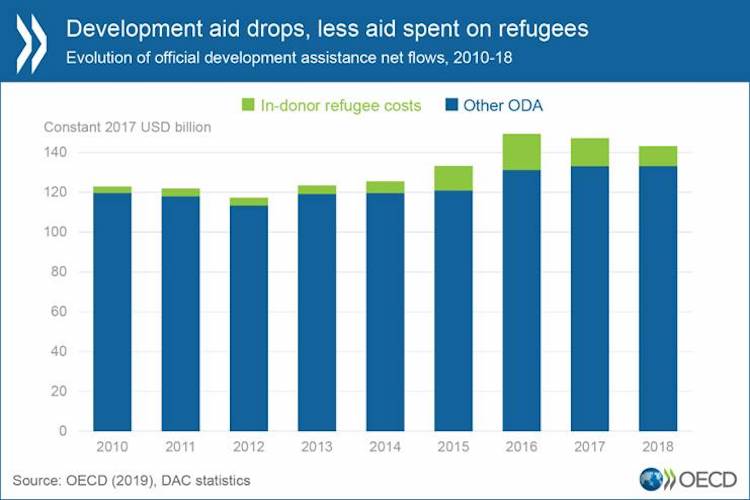

The warning of the head of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) comes at a time when, according to preliminary data collected by the OECD, official development assistance (ODA) from 30 member countries of the club of rich nations fell 2.7 percent in 2018 from 2017. The worst affected by the declining share were the neediest countries.

ODA makes up over two thirds of external finance for least-developed countries. The DAC is pushing for ODA to be better used as a lever to generate private investment and domestic tax revenue in poor countries to help achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Against this backdrop, Guria finds the picture of “stagnating public aid… particularly worrying as it follows data showing that private development flows are also declining.”

The aid decline, says the OECD, was largely due to less aid being spent on hosting refugees as arrivals slowed and rules were tightened on which refugee costs can come out of official aid budgets.

ODA from the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) totalled USD 153.0 billion in 2018 as calculated using a new “grant-equivalent” methodology adopted as a more accurate way to count the donor effort in development loans.

Under the “cash-flow basis” methodology used in the past, 2018 ODA was USD 149.3 billion, down 2.7 percent in real terms from 2017. Excluding aid spent on processing and hosting refugees, ODA was stable from 2017 to 2018, says the OECD.

Using the cash-flow basis ODA figure to compare 2018 with 2017 shows that bilateral ODA to the least-developed countries fell by 3 percent in real terms from 2017, aid to Africa fell by 4 percent, and humanitarian aid fell by 8 percent.

2018 ODA outflows rose in 17 donor countries, with the biggest increases in Hungary, Iceland and New Zealand. ODA outflows fell in 12 countries, due in some to fewer refugee arrivals, with the largest declines in Austria, Finland, Greece, Italy, Japan and Portugal.

The grant-equivalent ODA figure for 2018 is equivalent to 0.31 percent of the DAC donors’ combined gross national income, well below the target ratio of 0.7 percent ODA to GNI (Gross National Income). Five DAC members – Denmark, Luxembourg, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom – met or exceeded the 0.7 percent target. Non-DAC donors Turkey and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), whose ODA is not counted in the DAC total, provided 1.10 percent and 0.95 percent respectively of their GNI in development aid.

The latest ODA data follows the OECD’s recent Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development which found that foreign direct investment to developing countries dropped by around a third over 2016-2017, following a 12 percent drop in overall external finance from 2013-2016.

The 2018 ODA release marks the adoption of a “grant-equivalent” methodology, which the DAC agreed in 2014 would provide a more realistic comparison between grants, which made up 83 percent of bilateral ODA in 2018, and loans, which were 17 percent.

According to the OECD, whereas previously the full face value of a loan was counted as ODA and repayments were progressively subtracted, the grant-equivalent methodology means only the “grant portion” or the amount the provider gives away by lending below market rates, counts as ODA.

The loan parameters are set so that donors can henceforth only provide loans to poor countries on very generous terms. The new grant-equivalent figure is not comparable with historical ODA data and so the 2018 figures starts a new grant-equivalent ODA series.

“Less ODA is going to least-developed and African countries, where it is most needed. This is worrying,” said DAC Chair Susanna Moorehead. “This new grant-equivalent methodology is a more accurate and transparent way of measuring donor effort. It is also designed to incentivise donors to send the most concessional loans, and more grants, to the countries that need them most.”

The new methodology mainly affects ODA data for countries with high ratios of loans to grants in their 2018 ODA such as Japan (whose grant-equivalent ODA rises 41 percent versus the cash-flow measure), Portugal (up 14 percent), Spain (up 11 percent), Germany (down 3.5 percent) and France, Korea and Belgium (all down 3 percent). It barely affects ODA data for countries that provide the bulk of their aid as grants.

The OECD’s aid statistics include official flows from DAC donors to developing countries. The OECD also monitors flows from some non-DAC providers and private foundations. The preliminary data release each April is followed by final and detailed statistics at the end of each year with a detailed geographic and sectoral breakdown. [IDN-InDepthNews – 10 April 2019]

Graphic credit: OECD

IDN is flagship agency of the International Press Syndicate.

facebook.com/IDN.GoingDeeper – twitter.com/InDepthNews

Send your comment: comment@indepthnews.colo.ba.be

Subscribe to IDN Newsletter: newsletter@indepthnews.colo.ba.be