Viewpoint by Jonathan Power

LUND, Sweden (IDN-INPS) – “Since the days of the Roman Empire”, Daniel Kalder wrote in his book ‘The Infernal Library’, “dictators have written books, but in the twentieth century there was a Krakatoa-like eruption of despotic verbiage, which continues flowing to this day.”

It’s a strange thing but true that many dictators began their working lives as writers “which probably goes a long way towards explain[ing] their megalomaniac conviction in the awesome significance of their own thoughts.”

Lenin was the father of twentieth century dictator literature. He relied on the inspiration of Marx. Sitting in the comfort of his mother’s big, comfortable, house he translated “The Communist Manifesto”. Marx was then not well known – in 1883 only eleven people had turned up at his funeral. Contrary to Lenin and Stalin’s books and articles, Marx and Engels (his co-writer) had written a mesmerizing piece of work. In contrast Das Kapital was dense and over theoretical.

When he was exiled to Siberia by the Tsar Lenin read vociferously and wrote a 500-page book. The prose was tedious. The book failed to sell well.

Freed, he went to live in Switzerland where he wrote the highly influential book, “What Is To Be Done?” It made his reputation. His many barbs are directed not against capitalism or the Tsar but against other Marxists. It was elitist, arguing that the proletariat could not evolve into a revolutionary force by itself. Workers should submit to the guidance of ideologically pure radical intellectuals. Stalin, living in Georgia, read it and was inspired.

Lenin kept on writing for the rest of his life. Even in power he thought that writers could alter reality.

Stalin who inherited the crown was also a big-time writer, even though he was the son of an illiterate, drunken, father. He was attracted to Christianity and his mother sent him to the seminary where he learnt to read and write poetry. He had a sophisticated taste in books and did well in the seminary. His poems soon began to be published and are rated by scholars to be good.

He also read Marx and Lenin. He lost his religious faith and started to contribute articles to a Marxist newspaper. He was a popularizer. He appeared to be a compassionate man, loving oppressed peoples. He had empathy. In contrast Lenin, ensconced on his mother’s estate, turned his back on starving peasants, Stalin hadn’t yet discovered his capacity for wickedness. Unlike Lenin, Stalin had to practice before becoming a monster.

Stalin wasn’t a great thinker. After the Revolution he cranked out insubstantial articles for Pravda. Later, after Lenin’s death, he did write an important, accessible, work, “The Foundations of Leninism”. He found time, even in the midst of war, to keep on writing. He downplayed Lenin’s expectation of a swift transition to a “super revolutionary” period. Stalin was also a man of culture who loved classical music and the theatre. (Read Julian Barnes’s novel, “The Noise of Time” which describes the intimate relationship between Shostakovich and Stalin.)

Hitler was also cultured. He was a friend of Wagner’s widow. He liked Mendelssohn, even though he was Jewish. Although he was turned down by the art school in Vienna his paintings are not at all bad. He spent his time in prison reading books, even by Jewish writers. In Bavaria he began to move in literary circles. But when it came to writing Mein Kampf he over-wrote and badly too. He tried to pretend he was a great thinker. He wasn’t. He had trouble finding a publisher and it didn’t sell well. Even he admitted it wasn’t a good book. But he found he was a great orator and gave up writing.

Mao, who killed many more people than did Hitler or Stalin, was truly an intellectual, as Henry Kissinger who talked with him many times, has said. Before he got involved in politics he worked as a librarian.

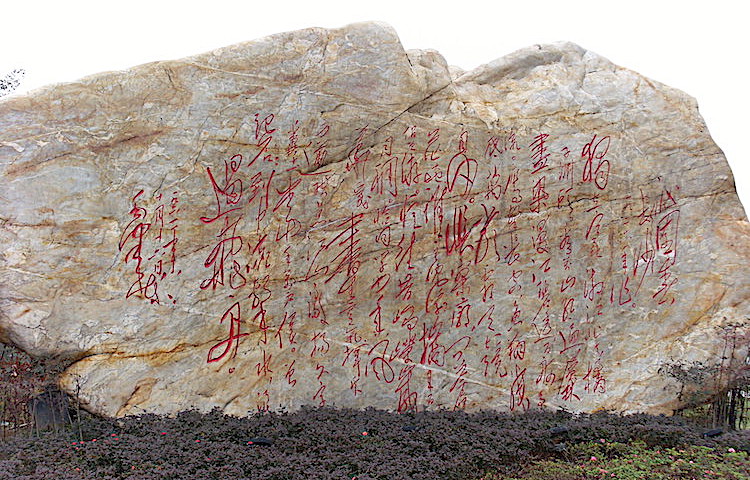

He wrote a less than gripping book, “Report on an investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan.” Then a quite good book, “A Single Spark Can Start a Prairie Fire”. Unlike Lenin and Stalin, he saw the peasantry as the force that would push forward a revolution. Later Mao would succumb to the labored prose of Marxist theory. His Cultural Revolution decimated all forms of artistic endeavor. Instead, one billion copies of “Quotations from Chairman Mao” were circulated.

Nearly all the big time twentieth century dictators had the writing bug: Kemal, Mussolini, Franco, Amin, Nasser, Gaddafi, Ceausescu, Kim Il-sung, Brezhnev, Khomeini, Andropov, Castro and Saddam Hussein. All of them were prose writers, some poets, and all convinced themselves that however busy they were with running a country they had to take time off to compose words.

On some days Vladimir Putin, Theresa May and Donald Trump seem to want to be dictators. Thankfully they show no inclination to write. May it continue like that!

Note: Jonathan Power was for 17 years a foreign affairs columnist and commentator for the International Herald Tribune. Copyright: Jonathan Power. Website www.jonathanpowerjournalist.com. [IDN-InDepthNews – 09 April 2019]

Photo: Mao’s calligraphy of his poem “Qingyuanchun Changsha”. CC BY-SA 3.0

IDN is flagship agency of the International Press Syndicate.

facebook.com/IDN.GoingDeeper – twitter.com/InDepthNews

Send your comment: comment@indepthnews.colo.ba.be

Subscribe to IDN Newsletter: newsletter@indepthnews.colo.ba.be