By Jan Servaes*

BRUSSELS | 28 April 2025 (IDN) — The debate on migration has calmed down a bit in the news media. However, this does not mean that the issue has been ‘solved’. Quite the opposite.

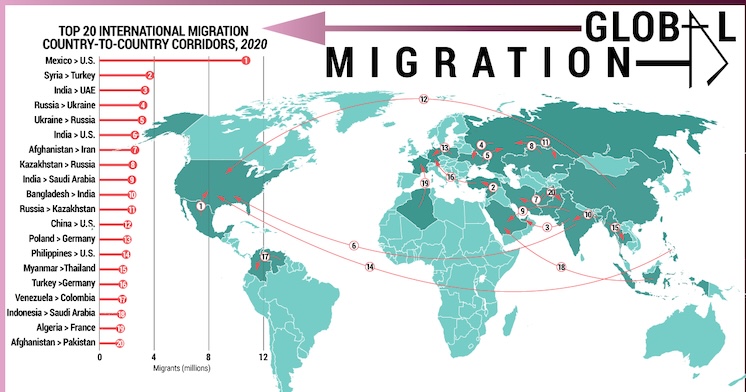

In most discussions about migration, we tend to start with numbers. Understanding the scale changes, emerging trends and demographic shifts associated with global social and economic transformations, such as migration, helps us understand the changing world we live in and plan for the future.

According to a global estimate by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) there were approximately 281 million international migrants in the world in 2020, representing 3.6 percent of the world’s population. The estimated number of international migrants has increased significantly over the past five decades, from 128 million in 1970 to 153 million in 1990. The latest figures for 2024 indicate 303,936,274 migrants.

There are currently more male international migrants than female ones worldwide, and the growing gender gap has widened over the past 20 years. In 2000, the male-female ratio was 50.6 to 49.4 percent, in 2020 it was 51.9 to 48.1 percent (with 146 million male migrants and 135 million female migrants). The share of female migrants has decreased since 2000, while the share of male migrants has increased by 1.3 percentage points.

It should also be noted that the vast majority of people remain in their country of birth — only one in thirty is a migrant.

Migration and human rights

The Mixed Migration Centre (MMC), part of the Danish Refugee Council (DRC), is a global network engaged in data collection, research, analysis, and policy and programme development in the field of mixed migration, with regional hubs in Africa, Asia and the Pacific, Europe and Latin America, and a global team based in Copenhagen, Geneva and Brussels.

‘Mixed migration’ refers to the cross-border movement of people, including refugees fleeing persecution and conflict, victims of trafficking, and people seeking a better life and opportunity.

The MMC aims “to advance understanding of mixed migration, positively impact global and regional migration policies, provide evidence-based responses to mixed migration for people on the move, and stimulate progressive thinking in public and policy debates on mixed migration.” The overarching focus of the MMC is on human rights and the protection of all people on the move.

People who participate in mixed migration are motivated by a variety of factors, have different legal statuses, and face diverse vulnerabilities. While they are entitled to protection under international human rights law, they are exposed to multiple violations of their rights along their journey. Mixed migration describes migrants who travel along similar routes, using similar means of transport – often travelling irregularly and aided in whole or in part by human traffickers.

Therefore, MMC uses the term ‘mixed migration’ primarily for three reasons:

First, the term is valuable to describe people who are on the move or in transit, regardless of the length of the journey. It cannot be applied to people before they have left their place of origin, nor to people who have arrived and settled in a place of destination.

Second, the term has value from a protection perspective, because people in mixed migration, regardless of their status, whether refugees or migrants, face similar risks and vulnerabilities during their journey due to the same causes and/or perpetrators.

Third, the term recognises that the drivers of migrant migration are diverse and often intertwined and influence each other: people feel compelled to migrate, including because of persecution and conflict, poverty, discrimination, lack of access to rights, including education and health care, lack of access to decent work, violence, gender inequality, the wider impacts of climate change and environmental degradation, separation from family and driven by aspirations.

Push and pull

The European Parliament identifies three push and pull factors as the main drivers of migration.

– Social and political factors:

Persecution because of one’s ethnicity, religion, race, political affiliation or culture can prompt people to leave their country. A key factor is war, conflict, persecution by the government or a significant risk. People fleeing armed conflict, human rights violations or persecution are more likely to be humanitarian refugees. This has an impact on where they settle, as some countries have a more liberal approach to humanitarian migrants than others.

Initially, these people are likely to move to the nearest safe country that accepts asylum seekers.

The backbone of international humanitarian law is available in the Geneva Conventions, which regulate the conduct of armed conflicts and seek to limit their consequences.

In recent years, people have been fleeing en masse to Europe from conflict, terror and persecution at home. Of the 384,245 asylum seekers granted protection status in the European Union in 2022, more than a quarter came from war-torn Syria, with Afghanistan and Venezuela in second and third place respectively.

– Environmental and climate migration:

The environment has always been a driver of migration, as people flee natural disasters such as floods, hurricanes and earthquakes. However, climate change is expected to exacerbate extreme weather events, potentially forcing more people to flee.

According to the International Organization for Migration, “environmental migrants are those who, because of sudden or progressive environmental changes that adversely affect their lives or living conditions, are forced to leave their usual place of residence temporarily or permanently and who move within their own country or abroad.”

It is difficult to estimate how many environmental migrants there are worldwide, due to factors such as population growth, poverty, governance, human security and conflict, which have an impact. Estimates range from 25 million to one billion by 2050.

– Demographic and economic drivers:

Demographic and economic migration is linked to poor working conditions, high unemployment and the overall economic health of a country. Pull factors include higher wages, better employment opportunities, higher living standards and educational opportunities. If economic conditions are not favourable and are at risk of further decline, more people are likely to migrate to countries with better prospects. According to the UN International Labor Organization, global labour migrants—defined as people who migrate for the purpose of work—numbered approximately 169 million in 2019, representing more than two-thirds of international migrants. More than two-thirds of all labour migrants were concentrated in high-income countries.

The World Bank collects global data on international remittances to assess the impact of economic motivations for migration. International remittances are financial deposits or in-kind transfers that migrants make directly to families or communities in their countries of origin. Available data reflect an overall increase in remittances over the past few decades, from $128 billion in 2000 to $831 billion in 2022.

The United States remained the largest source of remittances in 2023. The top five remittance countries in 2023 were India ($125 billion), Mexico ($67 billion), China ($50 billion), the Philippines ($40 billion), and Egypt ($24 billion). Economies where remittances account for a substantial share of gross domestic product (GDP)—underscoring the importance of remittances in financing current accounts and budget deficits—are Tajikistan (48%), Tonga (41%), Samoa (32%), Lebanon (28%), and Nicaragua (27%).

4Mi Interactive

4Mi Interactive is a portal maintained by the MMC for exploring and visualizing data on mixed migration routes worldwide. The dashboard contains data from over 79,000 interviews with migrants, and chronicles their journeys, aspirations, experiences and decision-making.

In its latest report, the MMC presents an in-depth analysis of migration trends, broken down by region.

For the Asia-Pacific region, the report ‘ Assessment of Community Perceptions and Information Needs of Persons at Risk of Irregular Migration in Bali Process Member States. Evidence from Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand ’ was published. In addition, data was collected from returnees in Afghanistan, as part of a project funded by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO).

Key points include:

– Cuts in US funding, including through Trump’s closure of USAID, are halting Afghan resettlement and leading to reduced aid to Bangladesh, Indonesia and Thailand;

– Thousands of Rohingya refugees flee Bhasan Char due to poor conditions and intimidation;

– Increased maritime patrols and intensified attacks on refugees in Malaysia;

– Renewed deportation plans for Afghans in Pakistan;

– Increased efforts to combat human trafficking linked to cyber fraud along the Myanmar-Thailand border; and

– Thailand’s violation of the non-refoulement principle: On February 27, Thailand deported Uyghur detainees held since 2014 to China, despite the risk of prosecution. The move has raised concerns about Thailand’s compliance with non-refoulement obligations. In March, the US imposed visa sanctions on Thai officials involved in the deportations, and a diplomatic visit to China by Thailand’s deputy prime minister to monitor the welfare of the deportees was met with skepticism by human rights groups.

East and Southern Africa, Egypt and Yemen:

– The war in Sudan continues to fuel displacement, with a sharp increase in cross-border movements to Egypt, Libya, South Sudan, the Central African Republic and Uganda;

– More than 70,000 arrivals in Burundi from the conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo represent the largest influx to Burundi in decades;

– Shipwrecks along the eastern route off the coast of Djibouti and Yemen provide an indication of the increase in failed migration attempts;

– The southern route to South Africa and the Indian Ocean route, en route to Mayotte and Mauritius, are also seeing more migrants.

Latin America and the Caribbean:

– The US government is blocking asylum at the southern border, suspending the resettlement programme and emphasising deportations.

– Migration northwards to the US is plummeting, with just 408 people crossing the Darién Gap in February – the lowest number in five years.

– The number of asylum applications in Mexico has reportedly tripled.

– New migration patterns from north to south have been observed, with the emergence of the Panama-Colombia sea routes to avoid the Darién.

– Ecuador ends regularization for Venezuelans, due to a lack of resources at the UNHCR and the IOM, leaving 3,000 visa applications in limbo.

North Africa:

– Tunisia has dropped out of the top 10 nationalities arriving in Italy, despite being in third place last year and the previous quarter.

– Libya remains the main departure point to Italy by sea, accounting for 93% of arrivals by sea, despite a 25% drop compared to the previous quarter.

– In March 2025, anti-migrant campaigns in Libya increased significantly. In early 2025, the route from eastern Libya to Greece has become increasingly important, as migrants increasingly choose alternative routes.

– EU-Tunisia ties are under scrutiny following reports of migrant abuse by EU-funded forces, including the expulsion and sale of migrants to armed groups in Libya.

– The UK and Spain are increasing migration control funding for Tunisia and Morocco respectively.

– Morocco stepped up interception and rescue operations in 2024.

West Africa:

– The refugee and asylum-seeker population in coastal countries (Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Togo and Benin) has increased by 5% in two months.

– Mauritania has launched a deportation campaign targeting migrants with illegal status.

– Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso are introducing a new shared passport in 2025.

– Niger is tightening rules on foreigners and reintroducing penalties, even for Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) citizens.

– The Guinean government has promoted cross-border transhumance (a form of pastoralism or nomadism, a seasonal movement of cattle between permanent summer and winter pastures) is temporarily banned, potentially disrupting grazing in West Africa.

– In January 2025, Togo and Gabon launched a two-year initiative aimed at strengthening migration management.

– More than 600 Nigerien migrants were expelled from Libya in January.

Europe:

– Less migrant traffic on most European routes compared to the first quarter of 2024.

– A Greek court ruled that Turkey should not be included on the government’s list of safe countries for return.

– Italy plans to transform migrant reception facilities in Albania into “return centers” for people with rejected asylum applications who are about to be deported.

– 4,400 unaccompanied minors in the Canary Islands will be sent to other regions of Spain.

– Spain will regularize the status of 25,000 migrants who fell victim to flooding in Valencia.

– Increasing EU surveillance and security in the Balkans.

– A new Polish law allows the government to suspend asylum rights.

– In the first months of 2025, there will be a shift towards more exclusionary policies in many countries, including Belgium, France, the Czech Republic, Austria and Germany.

– A survey of more than 1,000 irregular migrants in Brussels and Paris focused on migrants’ access to services, as well as their awareness and perceptions of voluntary return and reintegration (AVRR) programmes. The research results were presented publicly during an online webinar on 27 March 2025 and at the European Migration Network (EMN) policy event.

Belgium: The myth of a humane reception policy

Since 2013, Belgium has been structurally participating in the so-called European resettlement policy, adopted in 2015, accounting for an average of 433 people per year – a total of more than 5,200 people.

The European Commission promotes resettlement as an alternative to the often dangerous routes that many people take to flee. At the same time, it is an act of international solidarity with countries that receive large numbers of refugees. And importantly: the costs are not borne by Belgium, but via the European Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF).

Belgian Minister of Asylum and Migration Anneleen Van Bossuyt (N-VA) has recently decided to stop the resettlement program. According to Mieke Schrooten, this fits in with a “broader strategy of deterrence and muscle flexing”.

It is feared that stopping resettlement encourages irregular migration and opens the door to exploitation and abuse.

The minister announced that Belgium will conduct so-called “dissuasion campaigns” in countries such as Greece and Bulgaria via YouTube videos, websites and WhatsApp channels. The message: Belgium is full, don’t come here. “It remains completely unclear which criteria will be used to determine when the resettlement program can possibly be resumed”. That is why Schrooten rightly states, together with members of the scientific research team REFUFAM, that “the argumentation around stopping the resettlement program is very shaky. What remains is the observation that we are once again taking a step towards a more repressive and less humane asylum and migration policy”.

*Jan Servaes (PhD) was UNESCO Chair in Communication for Sustainable Social Change. He has taught International Communication in Australia, Belgium, China, Hong Kong, the United States, the Netherlands, and Thailand, in addition to several teaching and research stints at about 120 universities in 55 countries. He is known for his ‘multiplicity paradigm’ in “Communication for Development. One World, Multiple Cultures” (1999). Servaes was Editor-in-Chief of the Elsevier journal “Telematics and Informatics: An Interdisciplinary Journal on the Social Impacts of New Technologies.” He is the Editor-in-Chief of the Handbook of Communication for Development and Social Change (2020), the Springer Book Series “Communication, Culture and Change in Asia”, and the Lexington Book Series “Communication, Globalization and Cultural Identity”. [IDN-InDepthNews]

Image credit: IOM