By Roberto Massari*

This is the second of a nine-part series. Click here for Part 1.

BOLSENA, Italy (IDN) – Scene 2 [Dar es Salaam, 1965]

Holed up in the house of the Cuban ambassador in Tanzania (Pablo Rivalta, 1925-2005), recovering from the defeat of the military expedition in Congo (“la historia de un fracaso”, as Guevara himself called it) and before moving to Prague, Che wrote an important letter to Armando Hart Dávalos (1930-2017) on December 4, 1965. Armando Hart was a historic leader of the July 26 Movement [M26-7], husband of the founder of Casa de la Américas (Haydée Santamaría Cuadrado [1920-1980]) and father of “Trotskyist-Guevarist” Celia Hart Santamaría (1963-2008), as she described herself in her last few years, before dying in a car accident.

Armando Hart was the first Minister of Education in the Cuban government, from 1959 to 1965. He was then to become Minister of Culture from 1976 to 1997 and would leave a series of theoretical works, among which it is worth mentioning here the essay on Marx, Engels and the Human Condition (2005). We will see why.

After a premise in which Guevara informed Armando Hart of his revival of interest in studies on philosophy, the letter developed two fundamental themes: 1) desolate observation of the state into which studies on Marxism in Cuba were falling due to the lack of material except those produced in the Soviet world; 2) a well-structured study plan to be approved and implemented as soon as possible.

It should be noted that the premise contained Che’s admission that he had twice tried to deepen his understanding of the philosophy of “maestro Hegel”, always ending up defeated but with the conviction of having to start philosophical studies from scratch (see point 2).

Regarding the first point, Guevara said that there was no serious Marxist material in Cuba, excluding “the Soviet bricks that have the disadvantage of not letting you think, because the party has done it for you and you have to digest”, a method that Che defined as “anti-Marxist” and was based on the poor quality of available books (mostly of Soviet origin).

These were books published both for editorial convenience (since the USSR contributed financially, I add) and out of “disguise ideologue” [ideological tail ism/Vorticism] towards “Soviet and French authors”. By the latter, Guevara intended to refer to the official Marxists of the PCF – which at that time were the vogue, not only in France but also in various other Communist parties – gathered under the supervision of Roger Gaudy (1913-2012), at the time still a Stalinist, before embarking on the many turnabouts that were to lead him to convert to Islam in 1982.

With regard to the second point, it is not difficult to recognise an interpretative grid applicable to an important part of the reading plan that Che was to draw up in Bolivia about a year later, which has already been mentioned. This previous study project (which was personal, but which the Ministry should have also organised for the Cuban people) appeared divided into eight sections. And for each section some authors were indicated to be published or gone into further:

- The history of philosophy to be set within the work of a possibly Marxist scholar (mention was made of Michael Alexandrian Dinnik [1896-1971], author of a history of philosophy in 5 volumes), without obviously neglecting Hegel.

- The great dialectics and materialists. To begin with, Guevara cited Democritus, Heraclitus and Leucippus, but the Bolivian notes help us understand that he was also thinking of the work of Rodolfo Mondolfo (1877-1976), a well-known Jewish Italian Marxist who emigrated to Argentina in 1939 to escape the racial laws adopted by fascism. His history of El pensamiento antiguo (Ancient Thought) had been translated from Italian and published in various editions, starting in 1942.

- Modern philosophers. No names were made in particular, but Che did not exclude the publication of “idealist authors”, provided they were accompanied by a critical apparatus.

- Classics on economy and precursors. Adam Smith, the Physiocrats, etc.

- Marx and Marxist thought. Guevara complained that some fundamental Marxist texts were non-existent in Cuba and proposed the publication of works by Marx-Engels, Kautsky, Hilferding, Luxemburg, Lenin, Stalin “and many contemporary Marxists who are not totally scholastic”. This latter opinion was linked to point 7.

- Construction of socialism. With particular attention to rulers of the past and the contributions of philosophers, economists and statisticians.

- Heterodox and capitalist theorists (unfortunately collected under the same section). In addition to Soviet revisionism (for which Guevara could not but cite the Kruschev of the time), among the heterodox theorists he included Trotsky, accompanied by a cryptic annotation, almost as if to say that the time had come to take note that he had also existed and “had written things”. Among the theorists of capitalism, Marshall, Keynes and Schumpeter were cited as examples “to be analysed thoroughly”.

- Polemics. With the caution that Marxist thought had advanced precisely thanks to polemics, Guevara declared that one could not continue to know Proudhon’s Philosophy of Poverty only through Marx’s Poverty of Philosophy. It was necessary to go to the sources. Rodbertus, Dühring, revisionism (here referring to that of German social democracy), the controversies of the 1920s in the USSR.

This section was indicated by Che as the most important and the aim of a polemic directed against rampant conformism in the Cuban party and in the whole of the pro-Soviet world was evident. And it is no coincidence that the theme of “seguidismo” [“tailism”] reappeared in the conclusion of the letter, with a hint of veiled complicity addressed fraternally to Armando Hart against “the current makers of ideological orientation” to whom, according to Che, it would not have been “prudent” to show that type of study project.

An invitation to “prudence” that Armando Hart took a little too literally, deciding to keep such a precious text hidden for some decades.

But in addition to Che’s well-founded concerns, he had a special reason for not circulating the letter (and daughter Celia told me [in October 2006] that she could not forgive him when she came to know about it): the Cuban minister of Education had had and perhaps still had some special sympathies for Trotsky and had jealously kept it secret since it had never emerged in any of his books.

But Guevara – the only Cuban leader who had occasionally been interested in the Trotsky question – had somehow learned of it. For this reason, when he named the famous “heretic” in the letter, addressing Armando Hart he called him “tu amigo Trotsky” [“your friend Trotsky”].

In the Cuba of 1965, a month before the Tricontinental Conference (January 1966), in which the concluding speech by Fidel Castro (1926-2016) was going to mark officially and definitively the passage of Cuba into the Soviet field (which had already occurred in substance some time earlier), the suspicion of Trotskyist sympathies would have been incompatible with the government post he held. This is why the letter “disappeared” for over thirty years.

It would be published for the first time in September 1997 in Contracorriente (Year III, No. 9) and then by Hart himself in 2005, in the book on Marx and Engels cited earlier (pp. XLIII-XLVIII), with photostatic reproduction of the original pages.

It was in this way, only after having seen a text so precious for establishing the level of reflection on Marxism achieved by Guevara, that it became possible for those of us interested in doing so to provide a valid explanation for the reading plan sketched in the agenda of the Bolivian diary. In the words taken from Otro mundo es posible [Another World is Possible] by Néstor Kohan (b. 1967), the leading scholar on Che in Argentina:

“This letter allows us to grasp the degree of maturity achieved by Che regarding the need to seek an autonomous philosophical and ideological alternative to Marxist ‘orthodoxy’, including both the official culture of the Soviet Union and the officialism existing at the time in China” (Otro mundo es posible, p. 155).

At the time he wrote such an important letter, Guevara was going through a period of tumultuous transition, perhaps the most unstable and certainly the most dramatic of his life: he left Cuba and he had been defeated in the great economic debate; he resigned from government offices and had no citizenship; he was deprived of the support of his great friend Ahmed Ben Bella (1916-2012) who was overturned in June 1965 by the coup d’état of Houari Boumédiène (1932-1978) with which the decline of the Algerian revolution began; he had gone through the Congolese disaster; he was hostile to the Soviet policy of peaceful coexistence, and a lucid and fierce critic of the model of construction of socialism in the USSR; he was aware of the involution that the Cuban revolution was experiencing, anxious to return to what he considered to be a genuine revolutionary practice (guerrilla war); and he was wary of the theoretical certainties touted as “orthodox Marxism” and “Leninism”.

It was clear that the theoretical reflection he wished to resume in a systematic and almost “professional” form – and about which he had first spoken to Armando Hart (perhaps because he too had the faint smell of heresy…) – was in turn a product of more recent political delusions. There remained only the doubt about how ancient in the theoretical field were the “genetic” roots of those delusions which the new reflections should have remedied.

Roberto Massari, an Italian publisher, graduated in Philosophy in Rome, Sociology in Trento and Piano Studies at the Conservatory of Perugia. He has been President of the Che Guevara International Foundation since 1998 and is moderator of the Utopia Rossa (Red Utopia) blog. Translated from Italian by Phil Harris. [IDN-InDepthNews – 17 August 2018]

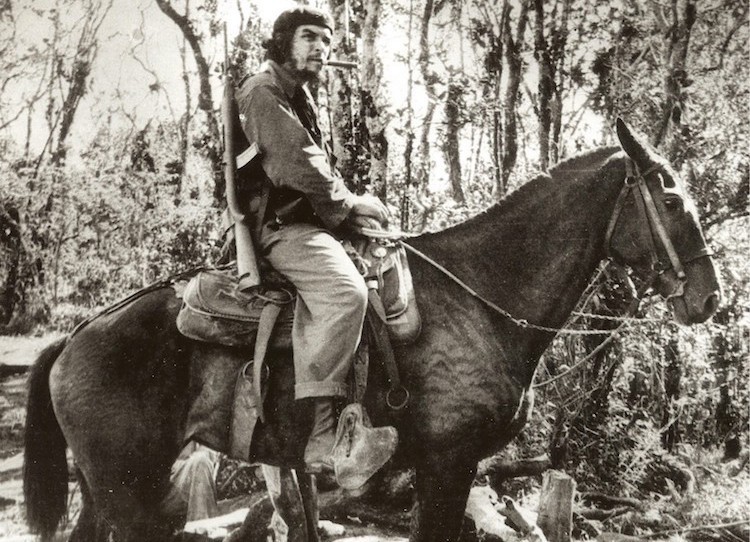

Photo: Guevara atop a mule in Las Villas province, Cuba, November 1958. Wikimedia Commons.

IDN is flagship agency of the International Press Syndicate.

facebook.com/IDN.GoingDeeper – twitter.com/InDepthNews