Viewpoint by Sergio Duarte

The writer is Former UN High Representative for Disarmament Affairs and current President of Pugwash.

NEW YORK (IDN) – It took patience from the President-designate of the 2020 NPT Review Conference, a sober assessment of the situation by a number of states, particularly from the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and help from the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs (UNODA). In the end, the parties to the Treaty agreed to postpone the Conference to next year, “as soon as circumstances permit, but no later than April 2021”.

The postponement was inevitable in view of the rapid spread of the new coronavirus. The decision leaves the door open for further consultations on procedural matters, particularly regarding the date and venue of the Conference. Some parties might have preferred to hold the Review Conference earlier, rather than later, and views on the most adequate venue were divergent, but common sense prevailed. The agreement provides a few month’s respite during which countries may ponder on how best to approach the Review Conference with a view to avoiding unnecessary confrontation.

As the world tries to mitigate the disastrous effects of COVID-19, one cannot avoid reflecting on still greater calamities, including nuclear war, the greater danger that the NPT seeks to avert. The effects of the use of nuclear weapons are well known and need not be overemphasized: they will not be limited by national boundaries; existing resources will not be sufficient to deal with the ensuing humanitarian consequences; the gravity and scale of the human toll, coupled with irreversible environmental damage may herald the end of conditions of survivability on the planet.

The widespread suffering caused by the current pandemic should therefore be a clarion call for greater understanding and cooperation among nations to deal with risks and problems that affect everyone and consequently require common solutions. Assuring that the Review Conference will strengthen the Treaty’s effectiveness and its vital contribution to peace and security has now acquired renewed timeliness and urgency.

On the substantive side there are a number of issues that need to be discussed constructively over the next months in order to facilitate a much-desired successful outcome in 2021. The last Review Conference ended without consensus on a Final Document, as was the case in four previous occasions.

Some features of the current panorama regarding nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation suggest the recrudescence of an atmosphere reminiscent of the one that prevailed during preparations for the 2005 Conference. At the III Session of the Preparatory Committee in 2004, sharp disagreement fueled by deep mistrust and outright hostility among delegations prevented it from arriving at requisite procedural decisions.

The Conference itself was thus unable to even start meaningful substantive work until it was too late to expect any substantive result. The failure served to rally political will from several quarters and to a large extent paved the way to the successful adoption of an ambitious Plan of Action in 2010.

In the years that followed, general concern about the recognition of the “catastrophic consequences” of nuclear detonations was decisive for the convening of three international meetings of governments and experts. Their conclusions provided the necessary impetus for the subsequent negotiation and adoption of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), whose relationship with and relevant contribution to the objectives of the NPT must still be better understood across political divides.

Pressing substantive issues also demands urgent consideration in preparation for the forthcoming Review Conference. Agreement on the important question of the Middle East Conference on weapons of mass destruction eluded the NPT 2015 Review. Middle Eastern states met in New York in November 2019 in an effort to keep the issue at the forefront of international concerns, despite the deterioration of the situation in the region and the indifference of key players.

Special attention must be given to how the 2021 Review Conference should approach this sensitive – yet crucial – subject. The consequences of lack of progress on this question since the 1995 Review and Extension Conference continue to haunt delegations and to undermine credibility in the Treaty.

In the last five years the international climate did not improve; on the contrary, the world became more unpredictable and unstable, as well as marked by a perilous trend towards self-centered attitudes and policies. Resumption of high-level talks among the major nuclear weapon States – particularly those possessing the largest arsenals – is essential to restoring the degree of confidence necessary for a successful outcome in 2021.

Early agreement on the extension of the New START beyond its expiration in February next year – that is, before the Review Conference – would be a welcome signal of the will of the two largest possessors of nuclear weapons to further reduce existing arsenals.

Such new reductions should not be considered as an end in themselves. Rather, they should be conceived and undertaken in explicit consonance with the commitment expressed in Article VI of the Treaty. By the same token, other nuclear weapon states should reinforce measures of restraint, avoid regional confrontation and work collaboratively to support and advance the goal of achieving their complete elimination.

Constructive proposals to reduce the risk of a nuclear war being started by accident or miscalculation have been made from different quarters. For instance, the five nuclear weapon parties of the NPT should jointly support the reaffirmation by the 2021 Review Conference of the Reagan-Gorbachev level-headed statement that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought”.

Related measures that have been on the table for some time deal with a no-first-use commitment or an agreed decrease in the operational readiness of nuclear forces. These, among other equally reasonable and responsible proposals, deserve serious examination.

The sharp differences between states and groups within the NPT can only be reconciled by means of a general recognition of the common interest in the preservation of the Treaty so that it can continue to play a major part in preventing new countries from acquiring nuclear weapons and in promoting their elimination, besides fostering peaceful uses of nuclear energy.

The NPT, however, is not a “done deal”, but a dynamic construct that can only survive if seen as fit for purpose to fulfill its three-fold objectives. Complacency and self-serving claims of “mission accomplished” in view of the success in curbing horizontal proliferation must not be allowed to overshadow the imperative for similar achievements in the development of peaceful uses and especially in attaining effective, legally binding nuclear disarmament measures.

The history of past Review Conferences shows recurrent dissatisfaction with the performance of the Treaty among many of its parties. An exacerbation of this pattern could lead to any or some of them to exercise the right ensured by article X.1 and leave the Treaty. This would create a major crisis and must be prevented. The answer, however, is not simply trying to buttress the conditions for withdrawal stipulated in the Treaty but rather to increase the confidence that it will more faithfully deliver on all its articles, without exception, thereby better attending to the interests of all its parties.

In the mid-1960’s the shared interest of the original promoters of the NPT – the Soviet Union and the United States – to limit the number of states acquiring nuclear weapons prompted the two superpowers of the time to lay aside their mistrust and hostility and join forces in order to steer the transit of their joint draft treaty through the Eighteen-Nation Disarmament Committee and the United Nations General Assembly.

The hesitation of a significant number of states to immediately subscribe to the Treaty gave way to a gradual recognition that it was indeed in their own interest not to develop such weapons. In adhering to the Treaty, such States accepted this as a legally-binding obligation, provided the other end of the bargain – nuclear disarmament – would also be complied with. The longer this objective is sidestepped and delayed, the greater discredit will the Treaty face.

Next May fifty years will have passed since the NPT entered into force. It has since become the most adhered-to instrument in the field of arms control and is rightfully considered the cornerstone of the non-proliferation regime. Up to the present, however, it has not produced the expected results with regard to the elimination of the threat posed by the existence of nuclear weapons. In spite of their commitment under Article VI the nuclear-weapon states have consistently increased the power of their arsenals and added new and ever more sophisticated instruments of destruction. They have stated their resolve to retain such arsenals for as long as they see fit and to use them in the circumstances they consider adequate.

No wonder that non-nuclear parties of the NPT show growing signs of exasperation with the neglect of NPT nuclear disarmament obligations. Such frustration led to the successful negotiation and adoption of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear weapons leading to their elimination, adopted by the United Nations in 2017. This new instrument clearly states the conviction of a majority of members of the United Nations that the humanitarian, social and environmental consequences of any use of nuclear weapons are not acceptable under international law and are contrary to the civilized standards of behavior among nations.

In his book Multilateral diplomacy and the NPT: an insider’s account, Ambassador Jayantha Dhanapala, former President of the landmark 1995 NPT Review and Extension Conference, observed: “Ultimately, the best guarantee against complacency is to be found in the level of confidence among the states parties in the basic legitimacy or fairness of the treaty. […] There is a persisting, widespread perception amongst many states parties that the fundamental NPT bargain is in fact discriminatory after all, as many of its critics have long maintained. So how can the states parties best prevent their hard-fought bargain from deteriorating into a swindle?”[1]

This is the urgent task that confronts all parties to the NPT. [IDN-InDepthNews – 12 April 2020]

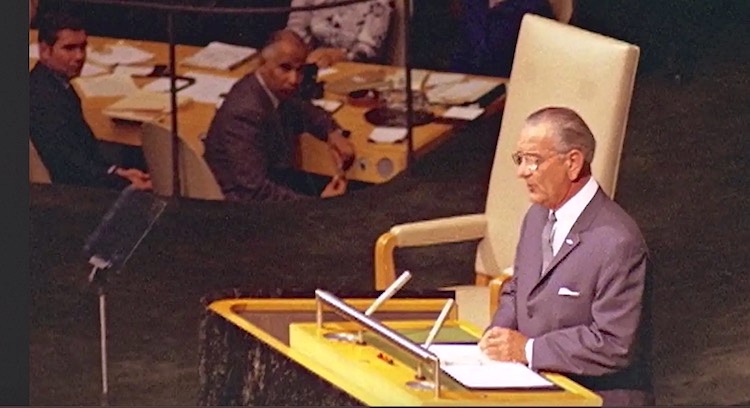

Photo: US President Lyndon Johnson addresses the UN General Assembly during the signing of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, 1968. Eventually, 188 countries signed the treaty, which was made into law in 1970. Photo credit: Screen capture from the documentary ‘Good Thinking, Those Who’ve Tried To Halt Nuclear Weapons’.

IDN is flagship agency of the International Press Syndicate.

facebook.com/IDN.GoingDeeper – twitter.com/InDepthNews

This article was produced as a part of the joint media project between The Non-profit International Press Syndicate Group and Soka Gakkai International in Consultative Status with ECOSOC on 12 April 2020.

[1] Jayantha Dhanapala, Reflections on the Treaty on the Non-proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (Solna, Sweden, SIPRI, 2017), p. 104/105.