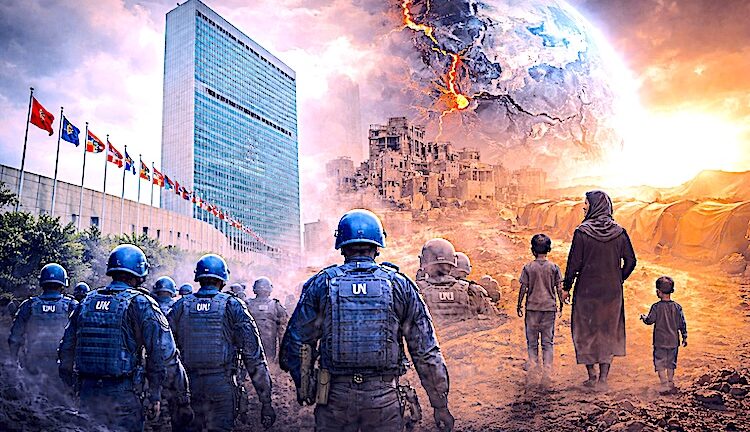

The UN’s failure and the rise of the Board of Peace

By Ramesh Jaura*

This article was first published on https://rjaura.substack.com/p/when-the-centre-no-longer-holds

BERLIN | 29 January 2026 (IDN) — As the Canadian prime minister concluded his speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos on 20 January 2026, the applause lingered, stretching just beyond the ordinary. It was not sparked by bold promises or grand unveilings. Rather, he did something unusual: he spoke with unvarnished honesty, laying bare the world as it is.

He declared that the rules-based order was not merely under strain, but dissolving. What leaders politely called “transition” was, in truth, a rupture. Power slipped through institutions’ fingers. Norms no longer shaped behaviour. Middle powers found that the old rules offered no shelter.

Washington wasted no time in responding, taking a sharply different stance. “Canada lives because of the United States,” came the blunt retort, a reminder that in some corners, hierarchy still trumps rules and dependence overshadows autonomy. Within days, Canada’s invitation to the new Board of Peace—a group meant to tackle global security as old institutions falter—was quietly rescinded.

The chasm between Davos applause and the backlash that followed exposes the heart of today’s world order: authority that cannot enforce, power stripped of legitimacy, and institutions unable to hold the balance.

Over a century ago, after another major crisis, W. B. Yeats wrote: “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold.” Today, that line feels more like a direct observation than just poetry.

A world that no longer resets

Wars now ignite with no clear end in sight. Ceasefires offer only brief interludes, rarely resolving the violence. Humanitarian crises stretch on for years, sometimes decades. Climate disasters outpace the slow steps of diplomacy.

Even when fighting stops, it often returns in new forms, such as proxy wars, insurgencies, blockades, cyberattacks, or economic pressure. Crises no longer feel unusual. Instead, it feels like we are always in a state of emergency.

At the heart of this stands the UN—present everywhere, decisive almost nowhere. It mediates, monitors, documents, and pleads. It gathers people, drafts reports, and sounds alarms. Increasingly, it cannot turn words into action.

This is not a failure of talent, commitment, or values. Anyone who has worked inside knows the depth of expertise and dedication. The real flaw is structural. The UN was designed for a world that believed in limits on rivalry, escalation, and ambition.

Those assumptions no longer hold.

The veto that became a shield

Nowhere is this clearer than in the Security Council. The veto, once a safeguard against catastrophe, has become a shield that lets countries dodge accountability.

Conflicts tied to permanent members or their allies escape enforcement. Resolutions are watered down or never see the light of day. Emergency meetings end with statements crafted to offend no one of consequence.

The outcome is more than inaction. It is a world where laws are wielded selectively. International law becomes less a shared standard, more a toolbox—picked up or set aside as needed. For those caught in conflict, this is not abstract. It determines whether they are protected or left exposed.

When people lose faith in fairness, they stop following the rules. Why should anyone obey rules that only apply to the weak?

Peacekeeping without peace

UN peacekeeping was once its proudest achievement. Imperfect, yes, but often effective. Blue helmets stood between warring sides, monitored fragile ceasefires, and helped guide shaky political transitions. They were deployed where peace, however thin, still lingered.

Today, such conditions are rare. Modern wars fracture within borders. Armed groups splinter. Consent is shaky. Neutrality is not just questioned; it is weaponized. Civilians are deliberately targeted.

Peacekeepers must shield civilians without real authority, maintain order without solid agreements, and cling to neutrality even when it paints a target on their backs. Their presence signals vigilance. If they withdraw, they are blamed for abandonment; if they remain, they are dismissed as powerless.

This is not a failure of courage. The flaw lies in the system’s very design.

Humanitarianism as endurance

Alongside peacekeeping, the UN’s humanitarian arm is more capable than ever. Its agencies are skilled, professional, and often heroic, delivering food, shelter, and care to places few dare to go.

Yet, they work in a space where politics offer little support.

Humanitarian workers bargain for access but cannot promise safety. They ease pain but cannot cure its source. Appeals echo year after year. Camps swell into cities. Displacement becomes a way of life.

The danger is that humanitarian aid works so well it keeps people alive in misery, allowing wars to drag on because the worst suffering is contained.

This was never meant to be a permanent form of governance. Yet that is exactly what it has become.

Climate: everyone’s problem, no one’s authority

Climate change exposes the system’s greatest contradiction. It is humanity’s most sweeping threat, yet it is tackled almost entirely by voluntary gestures.

Agreements multiply, targets are set, but emissions keep climbing. Adaptation crawls. Science shouts, but institutions whisper.

For many in the Global South, this is a second injustice layered on top of the first. Those least to blame for climate change bear the harshest costs, while the most responsible bicker over rules and timelines.

An agreement without teeth is not governance. It is hope, stripped of power.

When survival masquerades as success

The most deceptive thing about the United Nations is its survival. Longevity is mistaken for relevance. Institutions can linger long after they matter, sustained by habit, symbolism, and fear of what comes next.

The UN endures not because it resolves crises, but because no one agrees on what should replace it. This breeds the illusion that mere survival equals purpose.

Calls to reform the Security Council echo for decades, but nothing changes. The reason is simple: those with vetoes refuse to surrender them. Financing reforms are endlessly debated, yet key UN functions still depend on voluntary funds, warping priorities and making underperformance routine.

The UN’s moral authority once compensated for its lack of muscle. That glow has faded. When institutions fail to deliver, legitimacy erodes slowly—then vanishes in a flash.

This is failure without total collapse—the most perilous state for any institution.

The crisis beneath the crisis

This decline is linked to something deeper: the weakening of liberal democracy itself.

For decades, the UN got much of its moral strength from countries that claimed, sometimes honestly and sometimes not, to stand for accountability, legality, and rights. That moral centre has now weakened.

In the West, democracy often means rituals without unity, elections without trust, growth without stability. Polarisation stalls progress, emergencies multiply, and symbols stand in for substance.

People in the Global South see this with clarity. Nations that once lectured others on governance now stumble at home. Calls for a “rules-based order” ring hollow when rules are enforced for some and ignored for others.

This is why speeches about principles win applause in Davos, only to be forgotten days later. Honesty is welcomed, but it no longer sparks action.

What institutional failure looks like on the ground

Institutional failure is often discussed in abstract terms—vetoes, mandates, legitimacy, structure. But for those living through crisis, failure is painfully real and tangible.

It looks like meetings without decisions.

Peace talks announced and quietly abandoned.

Ceasefires that last just long enough for cameras to arrive.

In conflict zones, the UN flag still carries weight. Civilians recognize it, approach it, and hope for help. When protection fails, disappointment curdles into distrust—not just of the UN, but of the very idea of international restraint.

For aid workers, failure feels like exhaustion. Negotiations loop endlessly. Security guarantees evaporate overnight. Appeals are rewritten each year—numbers rising, hopes falling. Urgency remains, but response becomes routine.

For diplomats from smaller nations, failure is invisibility. They speak to empty rooms. Resolutions gather support, only to be felled by a single veto. Legal arguments are heard, then forgotten.

Over time, this changes behaviour.

Countries now shy away from firm commitments. They weave new partnerships—not out of rebellion, but because dependence is dangerous. They join many groups, sign multiple agreements, and sidestep promises others may break.

This is not cynical. In the Global South, many have long suspected that international law is applied selectively. Now, daily events confirm it. Wars go unpunished, aid is blocked without consequence, and climate damage grows unchecked. People learn quickly: protection is uneven, promises are situational.

This is why calls to “strengthen the rules-based order” ring hollow. Rules matter only when enforced. An order means something only if it restrains both the powerful and the powerless.

Institutions do not lose legitimacy in a single blow. It erodes bit by bit—with every conversation, every crisis, every letdown.

And when belief erodes, something else takes its place.

Sometimes it is raw power.

Sometimes it is regional arrangements.

Sometimes it is silence.

This is the soil where impatience grows—not just among the powerful, but among all those trapped between promises and reality.

Bandung, remembered differently

There is another tradition of multilateralism worth recalling—not as nostalgia, but as a serious alternative.

When Asian and African leaders met in Bandung in 1955, they did not reject the United Nations. Instead, they questioned the hierarchy within it. Their message was simple and bold: no civilisation has the right to decide the future for others.

Bandung never became a permanent institution. The Cold War, economic turmoil, and internal rifts intervened. Yet its ethical message endured.

Today, this spirit appears more in deeds than declarations. Countries avoid taking sides, forge many partnerships, and embrace cooperation—so long as it does not threaten their independence. Sovereignty is non-negotiable.

Many mistake this for defiance, but it is really adaptation.

The Board of Peace as a signal

In this context, the Board of Peace is less a solution than a signal.

The Board reflects, alongside President Donald Trump’s self-interest, a growing impatience—impatience with inaction, vetoes, and endless statements that yield no results. Its method prizes speed, concentrated authority, and tangible outcomes.

The Board’s appeal is obvious in a world where delay costs lives. But so are its dangers. Speed without legitimacy breeds domination. Effectiveness without consent sows resentment.

The Board worries supporters of the UN because it appears to sideline universality and the rule of law. Yet it attracts others, for legal promises without real protection now ring hollow. future, but it is a sign of what may come.

Why delay now is dangerous

There is a temptation, especially among multilateralists, to believe that time alone will heal. They hope institutions will outlast the storm, that consensus and reform will return. But institutional exhaustion rarely reverses. Outpaced structures are not gently reformed; they are bypassed. Authority slips away—sometimes quietly, sometimes with force—to wherever decisions are actually made.

Delay brings its own dangers. Every unresolved conflict becomes a precedent. Every unpunished violation invites the next. Every failed appeal teaches that restraint is optional.

The longer global governance appears paralyzed, the more tempting it becomes for countries, regions, armed groups, and private actors to go it alone. Fragmentation accelerates. Shared norms unravel. Escalation becomes effortless.

This is why the Board of Peace matters, even if it never materializes. It signals that people are already bracing for a world where universal institutions no longer call the shots.

If we wait too long to rebuild the system, what replaces it will be rough and unforgiving.

From “United” to “Federated”

Perhaps the problem begins with the name itself.

“United Nations” assumes countries share values, a common destiny, and a central purpose. The world no longer fits that mould. Power is scattered. Politics has shifted. Histories collide.

Instead, we may need a federated approach—not a world government, not a forced substitute, but a system that links countries without erasing independence, curbs power without moral grandstanding, and puts stopping organized violence first.

Such a federation accepts diversity as permanent. It swaps hierarchy for agreed boundaries. It promises not harmony, but survival.

The responsibility that remains

Discussing what follows the United Nations is not a rejection of its ideals. It is a call to match structure with purpose. When institutions lag too far behind reality, power rushes in to fill the void.

The Board of Peace is less a guide than a warning flare. It shows people are ready to improvise, legitimacy aside.

The real choice is not reform versus the status quo. It is whether we design a new system deliberately or let it be replaced by accident.

Yeats warned that the centre cannot hold.

He did not say we are free from responsibility for what happens next. [WorldView]

Original link: https://rjaura.substack.com/p/when-the-centre-no-longer-holds

Related link: https://www.eurasiareview.com/26012026-when-the-center-no-longer-holds-oped/

About the author: Ramesh Jaura is affiliated with ACUNS, the Academic Council of the United Nations, and an accomplished journalist with sixty years of professional experience as a freelancer, head of Inter Press Service, and founder-editor of IDN-InDepthNews. His expertise is grounded in extensive field reporting and comprehensive coverage of international conferences and events. Readers are invited to subscribe to https://rjaura.substack.com for complimentary updates or to support the author through paid subscriptions.