By Jan Servaes

BRUSSELS | 3 April 2025 (IDN) — Although the names of Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, or other (South African) ‘tech billionaires’ are not mentioned anywhere in Eric Louw’s “Afrikaner Identity: From Anticolonial Struggle Through Hegemonic Nationalism to Disempowered Minority,” this book offers an excellent introduction to understanding the ideology and some of Trump’s US government’s policies. After all, in my opinion, these can be found in the apartheid regime and Afrikaner identity.

Elon Musk and Peter Thiel, as privileged whites, grew up during the heyday of the apartheid regime in South Africa. Like many other whites, they emigrated around and after 1994, when apartheid officially ended and the ANC came to power with Nelson Mandela.

The author Eric Louw followed a similar path. He migrated to Australia, where I met him as a senior lecturer at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, when I was head of the School of Journalism and Communication there twenty-five years ago.

Who are the Afrikaners?

This book focuses on just one of South Africa’s ethnic groups, the “Afrikaners.” In the country of about 63 million people, eleven main languages were spoken in 2024. Afrikaans is recorded as 14%, next to Zulu (22%), Xhosa (16%), English (10%), Pedi (9%), Tswana (8%), Sotho (8%), Tsonga (4%), Swazi, (3%), Venda 2% and Ndebele (2%). About 40% of Afrikaans speakers identify as Afrikaners.

Louw attempts to answer some questions about these Afrikaners. Why have they become an identifiable group? How Afrikaner identity took shape over time. How Afrikaner-ness formed in relation to other groups in Southern Africa. How and why Afrikaner nationalism developed further in the twentieth century. What impact did this Afrikaner nationalism have on Afrikaner identity? What was the impact on Afrikaners when they became a politically powerless minority after 1994?

The Dutch East India Company (VOC)

The story begins in the seventeenth century with the migration of (Dutch, French and German) people who were initially brought together by the VOC (Dutch East India Company (1602-1799) at the Cape, as a stopover on the way to the Dutch East Indies, present-day Indonesia.

The Cape was never intended to become a European settlement colony. The VOC was a business enterprise — the first “transnational” avant-la-lettre – motivated by profit and trade with Asia rather than by the idea of creating a European colony in southern Africa.

The company did not invest large sums of money in establishing an administrative apparatus outside the immediate vicinity of Cape Town (as did the British). As a result, the VOC “outsourced” most of its governance to local communities. This style of minimal governance had a major impact on the formation of Afrikaner identity because it created a strong tendency toward local self-government and a general distrust of distant (impersonal) authority. Gradually, these groups coalesced into an ethnic group calling themselves “Boere” (Farmers) and/or “Afrikaners”.

In essence, Boer/Afrikaner identity came to encode a strong sense of self-reliance and a preference for self-government at the local level to establish authority in the family and in local communities.

The VOC thus monopolized and concentrated on trade with Asia, establishing colonies and trading in spices, slaves, and other goods. Another important decision the VOC made was to import slaves to meet the Cape’s labor needs.

The book then traces the story of these Boere/Afrikaners as they migrated east and north and settled in new areas. It was not until the twentieth century that “Afrikaner” became regularized as the way Afrikaners referred to themselves, with the terms “Boere” and “Afrikaner” being used interchangeably until the nineteenth century.

Crucially, these Boers no longer considered themselves Europeans. Calvinist values became a central feature of the emerging Afrikaner identity. This is why Christianity is a recurring feature in the Afrikaner story. A century and a half after the Huguenots arrived, their fervent Calvinism would be encoded in Afrikaner Christian nationalism, the ideology that spawned apartheid.

Similarly, the formation of Afrikaner/Boere identity also involved a long and complex journey that unfolded over time in three very different contexts: the Cape Colony, the Boer Republics, and then the United State of South Africa.

Afrikaner identity (and nationalism) thus emerged and mutated through five phases: the Dutch-ruled Cape; the British imperial era; the Boer republics; white hegemony of South Africa 1910-1994; and black-ruled South Africa since then.

Afrikaner nationalism

Nineteenth-century wars between these Boer/Afrikaners and the British, plus African tribes, influenced how they saw themselves and their relationships with other ethnicities around them.

The Boer War (and how it consolidated British hegemony over Southern Africa) had a particularly powerful influence on the formation of Afrikaner identity and on stimulating the growth of Afrikaner nationalism. And this Afrikaner nationalism would have a profound impact on all South Africans. Although Afrikaners were a minority group, they had a disproportionate influence in South Africa. Their ubiquity stems from how history has embedded Afrikaners in the fabric of the entire country, Louw argues.

He examines in detail the rise of Afrikaner nationalism (during the first decades of the twentieth century) and how Afrikaner nationalists came to dominate the political system from 1948 to 1993.

To understand this nationalism, the role it played in shaping the evolution of Afrikaner identity, and Christian nationalist identity in particular, is also examined.

The differences between pre-nationalist, nationalist and post-nationalist Afrikaner identities are also discussed.

A caste society based on race and slavery

The VOC’s decision to use slave labour created a (race-based) caste society in the Cape. The British Empire later spread this model of society throughout southern Africa. In effect, the Cape became the fulcrum that produced not only Afrikaners and Coloureds but also a form of social and economic organisation that became the model for all states in southern Africa, from South Africa to Zambia.

Britain seized the Cape in 1795 to prevent it from falling into French hands during the Napoleonic Wars (after France had conquered the Netherlands). In 1806, the Cape Colony was formally transferred from the Netherlands to Britain.

The British introduced the British monarchy, Anglo-liberalism and the English language to the Cape. The two largest ethnic groups were Boers/Afrikaners and Coloureds.

In 1822, the British Governor made English the official language of the Cape Colony. The change of the official language and the growth of a significant English population in the Cape represented a significant reconfiguration of the cultural environment. This caused political unrest among Afrikaners/Boers, who, in the 1820s, began to seek new areas to colonise beyond the Cape’s northern borders and beyond the British government’s reach. This would eventually lead to the Great Trek (1835-1840), when approximately twenty percent of the Cape Colony’s population migrated out of the colony to escape British rule and establish their own Boer republics.

Anglo-liberalism

The second major socio-economic change introduced by the British was the abolition of slavery in 1834. This severely disrupted the Cape’s agricultural economy and the lack of consultation caused great discontent among the Boers, so many farmers joined the migration to the Boer republics in the north.

The end of slavery, together with the immigration of Anglo-Saxon settlers and the growing influence of British missionaries, spread the influence of Anglo-liberalism within the Cape Colony.

Afrikaners opposed this. In 1875, an Afrikaans language society was founded, the Genootskap van Regte Afrikaners (Society of True Afrikaners). This society sought to promote Afrikaans, produce an Afrikaans dictionary, and publish an Afrikaans Bible translation. This language movement is seen as a key moment in the emergence of a specifically Afrikaner identity that would evolve into Afrikaner nationalism. But it was the twentieth-century Afrikaner nationalists in the Union of South Africa who consolidated this shift and entrenched the use of “Afrikaner.”

However, the British Empire did more than influence South Africa’s cultural and linguistic milieu. A major result of the discovery of diamonds and gold was that it transformed Southern Africa from an arid, sparsely populated hinterland into a place attractive to the British Empire.

Diamonds transformed the economy of the Cape Colony. After Cecil Rhodes industrialised Kimberley’s diamond production (through his company De Beers) wealth flowed throughout the colony, resulting in a major period of railway construction and economic development. It also attracted many new Anglo-Saxon settlers to the colony.

Rhodes also pioneered a new mining model that took advantage of the abundant unskilled (low-paid) labour in Africa. He built a system of black migrant labour that nestled within the British Empire’s model of social segregation.

Previously, the British had been primarily interested in the Cape as a naval base to secure their trade route between London and India. But now, Southern Africa began to look like a place that could generate enough wealth to help finance the costs of Britain’s Indian Ocean empire.

This new British interest in the region resulted in four wars. In 1879, Britain began three wars designed to weaken the power of the three largest tribes in Southern Africa: the Xhosa, Zulu, and Pedi.

Mergers of the Voortrekker republics produced two Boer republics. These republics were largely extensions of the Cape Boer culture, and throughout the nineteenth century, their populations continued to grow due to a steady stream of Afrikaner/Boer migrants from the Cape Colony.

A British Empire

The first half of the twentieth century was a successful one for Britain. It won the Boer War and established the Union of South Africa as a British Dominion. Anglo-settlers were economically and culturally dominant in this Union, which functioned to strengthen Britain’s power worldwide. South Africa, for example, fought for Britain in two world wars.

However, although Britain successfully exercised hegemonic control over South Africa from 1910 to 1948, according to Louw, three mistakes were made. Each of these mistakes contributed to the growth of Afrikaner nationalism, which eventually came to power in 1948.

The first of these mistakes was to allow many Afrikaners to become impoverished after the Boer War. In the 1930s, about 25 percent of Afrikaners lived in abject poverty and in mixed slums. What became alarming to Anglo-capitalists in South Africa was the growth of anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist ideologies among these impoverished people.

Prime Minister Botha made the second mistake in handling the 1914-15 uprising, and Prime Minister Smuts made the third mistake in handling the Rand uprising of 1922.

All of these mistakes fueled the rise of Afrikaner nationalism. For many South African Anglos, the 1948 election was an existential shock, as the Union they had created had just been taken away from them. But the most important reason 1948 was a turning point was that it began the apartheid era.

Integration, segregation or apartheid

Chapter 3 of the book delves deeper into the politics that led to the 1948 elections and how apartheid emerged. Louw explains that radical nationalists invented apartheid because they argued that South Africans had to choose between three options, namely integration, segregation or apartheid.

Segregation versus integration had long been debated in the Anglo-Saxon world, but especially after the founding of the National Party (NP) in 1914, it was argued that the debate needed to be broadened to include a third option, namely, complete partition (or apartheid).

Integration meant that different ethnic groups were brought together economically, socially and politically into one shared country. There would be no distinction or separation between these ethnicities. Instead, they would all mix freely with each other. Hybridisation and cultural homogenisation were the likely outcomes. South African political parties such as the ANC advocated integration. The NP rejected integration because it would result in minority groups (such as Afrikaners) being culturally submerged by larger ethnic groups.

Segregation involved bringing different ethnic groups together in a shared economy but socially separating them after work hours (e.g., through residential segregation). This model of working together/living apart encouraged cultural homogenization but discouraged hybridization. The British Empire had implemented segregation in many places (including South Africa). South African political parties such as the SAP and UP advocated segregation.

Apartheid involved the complete division of ethnic groups into separate nation-states/countries. Each ethnic group was given its own homeland, state, economy, and government. While segregation involved half division/half integration, apartheid involved complete division/separation. The NP rejected both segregation and integration in favor of apartheid. Apartheid theorists rejected segregation because it was too costly in the long run.

Therefore, apartheid was based on NP principles. First, each ethnic group had the right to cultural identity and language. Second, because South Africa had multiple different ethnic groups, a full division model (no segregation) was needed to give each ethnic group its own rights and institutions. Each ethnic group had the right to its own cultural institutions (e.g. schools and government); sovereign national homeland; and institutions that enabled cultural reproduction.

The Afrikaner Imaginary Community

Chapter 4 focuses on the role of the media in constructing Afrikaner nationalism and the Afrikaner imaginary community.

This imaginary community that grew in the first half of the twentieth century developed an identity shaped by three phenomena. First, they lived in a society dominated by Anglos who treated Afrikaners as a lower class. Second, many Afrikaners had been driven off the land after the Boer War and moved to urban slums. The economy built up by the British after the war and rapid urbanization had impoverished about 25 percent of Afrikaners. Third, the power of English as a world language was perceived as a real threat to the survival of Afrikaans.

Living in a modern capitalist economy/society run in English created the daily experience of how the British Empire and global Anglo-Saxon culture functioned to aggressively assimilate smaller cultures and absorb smaller peoples/languages (such as Afrikaners) into a homogenized global (Anglo-Saxon) culture.

But the experience of judgmental, mocking Anglos condescendingly treating Afrikaners as inferior created precisely the conditions for the growth of Afrikaner nationalism. This, according to Louw, led to a form of resistance that can be called catch-up nationalism.

The Post-Nationalist Shifts After 1994

Afrikaners faced post-nationalist shifts after 1994 can be divided into two types of change. First, there were major contextual changes in the external environment in which Afrikaners lived (as it did not take long for the ANC leadership to show hostility towards Afrikaner values and interests). Second, Afrikaners’ internal life experiences necessarily underwent a series of shocks as they were affected by the major changes wrought in their world by ANC policies.

From 1948 to 1994, the NP’s language policy for government bureaucracies was bilingualism (English and Afrikaans). But shortly after the ANC came to power, the use of Afrikaans as a language of government/bureaucracy disappeared. Central, provincial, and local government, plus state-owned enterprises and government research institutes, used only English.

For example, the use of Afrikaans on SABC television was drastically reduced. Before 1996, Afrikaans was used for 50 percent of TV1 broadcasts, but this was reduced to only 14 percent of TV2 broadcasts.

Furthermore, Afrikaans was systematically eliminated as a sign language on road signs, airports, train stations, etc. Even more alarming to Afrikaners, the government began forcing Afrikaans schools, colleges and universities to switch to English-language instruction. Afrikaans teacher training colleges were closed.

And then came Mandela’s speech at the 1997 ANC National Conference, in which he effectively renounced reconciliation and told whites to apologise for the crime of apartheid.

During the presidencies of Mbeki and Zuma, unrest turned to concern and then to alarm as the ANC’s actions were seen as an attack on the interests of both Afrikaners and Anglos. Afrikaners were the first to publicly voice their concerns in 2005, and Anglos joined in 2007.

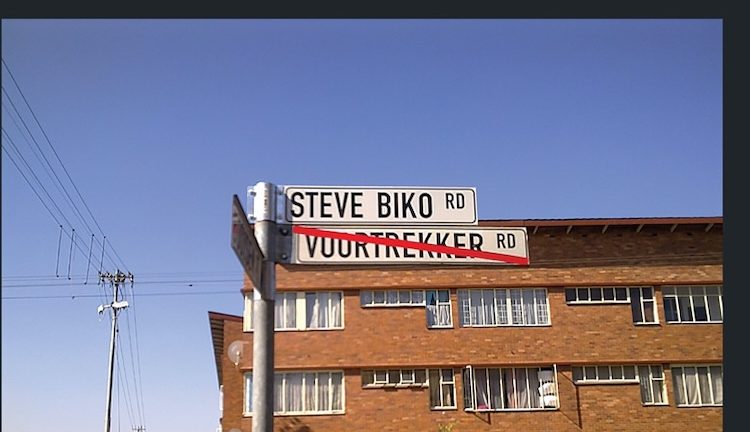

The trigger in 2005 was when the ANC began replacing Afrikaner-sounding place names with black African names in the northern part of the country. Afrikaners reacted angrily to the renaming of Pretoria plus a series of towns in Limpopo Province. The renaming process challenged their sense of belonging and rootedness in the country and was seen as an attack on Afrikaner history. White South African history was vilified, statues were attacked and white art and libraries were burned.

A South African diaspora abroad became visible at this stage with the steady emigration of non-black South Africans.

Two (interrelated) ANC discourses contributed much to this exodus, namely the ‘transformation’ and the ‘majority’ discourses. The ‘transformation’ discourse was about transforming South Africa into a truly African society. According to Louw, this ‘transformation’ discourse promoted a Marxist-Africanist interpretation of South African history and society that necessarily attacked and undermined the way Afrikaners and Anglos saw themselves and the society they had built. For Afrikaners who saw themselves as Africans – that is, a product of and rooted in Africa – this was deeply alienating and destabilised their sense of who they were.

Uncertain future?

What became clear after the unrest in July 2021, in which 354 people were killed and 5,500 arrested, is that white South Africans became more attentive to the ANC government and its failings. They became politically involved because the ANC’s poor governance now threatened their future well-being. There was now talk of an incompetent state and the threat of a failed state.

When whites now talk about the ANC, they talk about how the incompetence, mismanagement and corruption of the ANC destroyed the excellent infrastructure that the ANC inherited in 1994, and how the evolution into a failed state is now a real threat to their future. [IDN-InDepthNews]

Reference

P. Eric Louw, “Afrikaner Identity: From Anticolonial Struggle Through Hegemonic Nationalism to Disempowered Minority”, Academica Press, Washington DC, 2025, 306pp. ISBN: 9781680533415. https://www.academicapress.com/node/646