By Jan Servaes*

MIAMI, USA. 29 September 2023 (IDN) — “As many people who know Cuba and Miami well have observed, each is a peculiar mirror of the other. … It is impossible to understand the Cuban Revolution without understanding Miami, and it is impossible to understand Miami without understanding the Cuban Revolution,” writes Ada Ferrer on page 419 of her masterful Pulitzer Prize Winner book: Cuba. An American History. Ferrer has been the Julius Silver Professor of History and Latin American and Caribbean Studies at New York University since 1995.

On previous occasions, Miami was a stopover for me on the way to Latin America. Now that I have been in Miami for a few weeks, I have become fascinated by this cultural, ideological and ethnic melting pot.

Ada Ferrer’s book has served as a good guide. It is an attempt to correct and partly even refute the binary interpretations of Washington and Havana. It covers more than five centuries and makes us witness the development of the modern nation, with its dramatic record of conquest and colonization, of slavery and freedom, of independence and revolutions made and failed.

Along the way, Ferrer explores the sometimes surprising, often tense intimacy between the two countries, documenting not only the influence of the United States on Cuba, but also the many ways in which the island—90 miles off the coast of Florida—has been often present in American affairs. The common thread that runs through the 33 engaging and well-written chapters is the presence of Cuba’s larger neighbor to the north.

Another important goal of the book is to foreground within mirror histories the experiences of ordinary communities and people who have had little access to power.

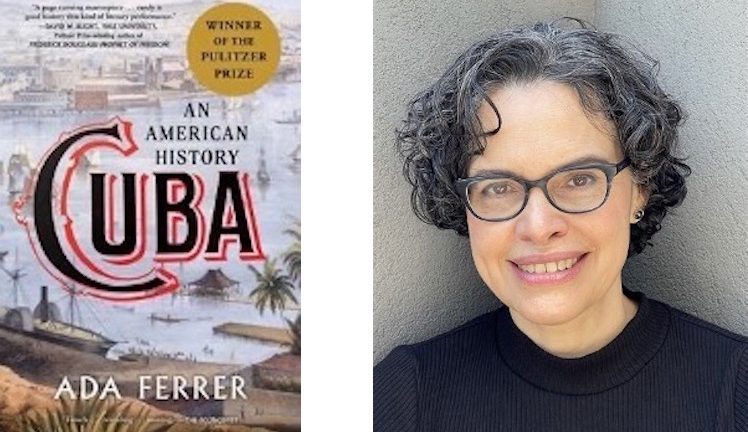

Ada Ferrer

Ada Ferrer was born in Cuba but raised in the United States. She has been traveling to the island since 1990 for research and to visit family and friends.

This is not Ferrer’s first widely acclaimed book. She is already the author of “Insurgent Cuba: Race, Nation, and Revolution, 1868–1898, ”winner of the Berkshire Book Prize for the best first book by a woman in any field of history, and “Freedom’s Mirror: Cuba and Haiti in the Age of Revolution,” which won her the Frederick Douglass Book Prize from the Gilder Lehrman Center at Yale University, as well as multiple awards from the American Historical Society.

The ‘Bumpy Road’ operation

On April 17, 1961, CIA-backed Cuban exiles carried out an ambitious amphibious landing on a remote part of the Cuban coast. The now infamous Bay of Pigs —the CIA codenamed it “Bumpy Road”—was a military failure. If the invasion had succeeded, Washington expected the end of the nascent revolution in Cuba.

“It is expected,” reads the 4 January 1961 CIA report, “that these operations will precipitate a general uprising throughout Cuba and cause the revolt of large segments of the Cuban Army and Militia.” Ada Ferrer cynically notes that such a view was “optimism bordering on lunacy” (p. 359).

In reality, most Cubans were more than happy to see the departure of Fulgencio Batista, the US-backed military dictator who had dominated Cuban politics on and off since 1933.

It was only when, around 1963, Castro’s regime took a clear turn towards state-led socialism that domestic opinion became divided. Thousands of Cubans fled the island where they were born (including Ferrer’s parents), and most tried to settle in Miami.

“Americans owned so much in Cuba, and Washington was so accustomed to wielding power there, that for the revolution to follow through on its promises necessarily threatened US interests. As US hostility grew increasingly apparent, it was easier for the Cuban government to defend radical measures not only on the basis of any inherit merit, but also on the basis of sovereignty and patriotis. … But the outlines of a major conflict were present almost from the start and becoming clearer by the day” (p. 350).

The antipathy of Cuban exiles towards Castro set the framework for the perception of a large portion of American citizens (and politicians!) about the island nation; for many, little has changed in all these years.

Those Cubans who remained were pushed to the other extreme and came to see their nearest neighbor as an imperialist capitalist overlord.

Parallels

Ada Ferrer attempts to bring some perspective to this polarized historical debate. Relations between the US and Cuba have not always been frosty, she points out. Roughly a century before Cuba’s break with Spain, the cultural, economic, and political ties between these two American territories were wide and deep. Sugar, Ferrer argues, brought Cuba and the United States into a profound historical parallel: the shared experience of slavery. In the sugar cane fields of Santiago de Cuba and on the cotton plantations of Mississippi, life was governed by exactly the same barbaric conditions and inhumane logic.

‘Sugar and slavery’ have linked Cuba and the US since the English landing in 1762. “The British occupation did not create Cuba’s sugar industry, but it did give it a commanding boost. It was a harbinger of a new Cuba—and a lasting one” (p. 53).

According to The Guardian, Ferrer is clear about this: “Cuba—sugar, its slavery, its slave trade—is part of the history of American capitalism.”

The slave trade did not stop when England and Spain officially ended it in 1807. What’s more, “of all the Africans forcibly transported there over the course of three and a half centuries, more than 70 percent arrived after Spain illegalized the trade in 1820. (Moreover), Americans were deeply implicated in that illegal commerce” (p. 92).

Another parallel is that of colonialism. Both countries have been subject to European (England and Spain) powers. Yet the United States shifted from colonized to colonizer at the first opportunity.

Ferrer summarizes the role of the US in the so-called ‘liberation’ of Cuba in 1898 as follows: “The American intervention in 1898 … was not intended to help the Cubans achieve a victory over Spain. In any case, it was coming. The American intervention was precisely intended to block this.” “In December 1898, representatives of Spain and the United States met in Paris to sign the treaty that sealed the end of Spanish rule over Cuba. Again, Cubans were denied a seat at the table” (p. 165). “In 1820-21, more than 60 percent of the sugar, 40 percent of the coffee, and 90 percent of the cigars imported into the United States came from Cuba” (p. 86).

The Monroe Doctrine of 1823 stated that the Western Hemisphere was no longer open to European colonialism. European nations should also not interfere with the United States’ planned territorial expansion. The US could, therefore, take the place of Europe.

“In the struggle between Cuba and Spain,” Ferrer writes of the American intervention in the Cuban War of Independence, “it was the US that emerged victorious. It was this emerging system that the Monroe Doctrine protected and enabled. While the policy attempted to limit European power in all of Latin America, it played a very specific role with respect to Cuba. By seeking to shield the island from the influence and power of Britain—the world’s greatest naval power turned crusader against the slave trade—it bolstered slavery and safeguarded a whole range of US investments there. The Monroe Doctrine, simply put, protected Americans’ stake in Cuba” (p. 94). Therefore, after the Spanish defeat in 1898, it was the Stars and Stripes that was hoisted over Cuba.

US-Cuba

Everyone has an opinion about Cuba and US-Cuba relations. But the question is often whether this is based on more than ideology. The fact is that in 1961, at the height of the Cold War, the United States broke diplomatic relations with Cuba and imposed an embargo.

The impasse has persisted for more than half a century—during the terms of ten American presidents and the fifty-year rule of Fidel Castro. His death in 2016 and the retirement of his brother and successor, Raúl Castro, in 2021 have once again raised questions about the country’s future.

Meanwhile, politics in Washington—Barack Obama’s visit promising “normalization” in 2016, Donald Trump’s reversal of those policies and the election of Joe Biden—have once again made the relationship between the two nations a subject of debate.

US President Obama and Cuban leader Castro at Estadio Latinoamericano during Obama’s visit to Havana. [State Department photo/ Public Domain]

Barack Obama was the first US president in office, after President Calvin Coolidge in 1928, to visit Cuba in March 2016. Obama openly declared his opposition to the US embargo, telling Cubans that “we share the same blood,” echoing the words of his announcement of possible normalization on December 17, 2014: “Todos somos Americanos.” “We are all Americans.”

“Obama stated the obvious: Washington’s Cuba policy had never worked; there was no logical reason to continue it. He also broadcast his willingness to enter into bilateral talks with Cuba – without any preconditions” (p. 455). Ferrer is pleased with this. “Here was a modern American president using the word ‘American’ as something other than a synonym for the United States.”

However, with only eight months to live, 89-year-old Fidel Castro was not convinced. “The first thing we must consider,” he wrote in the state newspaper Granma, “is that our lives are but a fraction of a historical second and that humans tend to over-value their role in history” (p. 462).

Obama and Washington quickly provided proof of Fidel’s hypothesis. For instance, though Obama issued an executive order calling for the closure of the US detention center at Guantanamo, it has remained in use even up to today.

Ben Rhodes, the deputy national security adviser during Obama, who is credited in Ferrer’s book as the architect of the Obama administration’s all-too-brief normalization of relations with Cuba, told Ferrer that he wished he could have read “Cuba: An American History.” before starting that project.

When the 45th American president, Donald Trump, took office, not much was left of the Obama approach. Before Trump took office, he had already investigated the possibility of building hotels in Cuba, contrary to American law. The ban on money transfers was also reinstated, although Cubans in the United States were allowed to send cash aid to relatives on the island during the decades of embargo prior to Trump’s order in November 2020.

The current US government under Biden also says, in addition to empty expressions of support for the Cuban people, that its Cuba policy is “on pause”.

Ferrer’s story of long kinship and shared history could provide a strong foundation for better mutual understanding. But for now, both countries appear to be in the grip of paralysis and stasis. The main difference is that the US embargo strategy consistently fails to achieve its goal (assuming that the stated goal remains the overthrow of the Cuban government), while the Cuban government (with difficultly) manages to stay in power. The European Union is currently Cuba’s largest export and trade partner and the largest foreign investor on the island.

Looking from the outside

The capital of Cuba and by extension the island itself was once known as the ‘key to the New World’. Oliver Balch of Americas Quarterly therefore states: “Through the story of one small island, ‘Cuba: An American History’ allows Americans to see themselves through the eyes of others.”

More than a century ago, José Martí, Castro’s revolutionary muse, did the same thing in reverse. In New York in the 1880s and 1890s, Martí saw first-hand the harsh reality of economic and racial inequality—and decided his homeland needed to take a different route.

Martí hoped that true Cuban independence, reinforced by strong solidarity with the rest of Latin America, could keep the growing imperial power of the United States in check.

That is not the history Ferrer can tell. After the sugar boom, after World War I, “money, time, climate and proximity all contributed to Cuba’s popularity as a tourist destination for Americans. But so did something entirely different: American morality … and Prohibition, the ban on the production, transportation, and sale of alcohol” (p. 220). “Gambling, drinking, everything seemed to be legal in Cuba. And that became an important part of how Americans understood Cuba. US travelers extolled the island as a place where anything was possible” (p. 221).

Ferrer’s story could give Americans unexpected insights into their own nation’s history, and thus help them imagine a new relationship with Cuba. Or, as The Economist puts it: “Readers will end this fascinating book with a sense of hope.”

Hope

After all, Ferrer concludes her book with the hope that Cuba and the United States will have a future that is “more than the sum of the actions of the two governments in question.” The book convincingly shows that the past was much more than that.

“That effort could also allow us to understand the present and the future differently, too. If every present is a kind of crossroads, then that seems especially true now, when so much – from the planet’s fate to the possibilities for racial and economic injustice – seems to be on the line. This particular present may contain within it the possibility for a new relationship between Cuba and the United States, a chance to move beyond enmity of the past sixty years and the unequal impositions long before that. But that future – like the past – will harbor the lives of billions” (pp. 469-70). It is and remains a ‘bumpy road’.

Reference:

Ada Ferrer, Cuba. An American History

Publisher: Scribner, Simon&Schuster (June 28, 2022)

576 pages

ISBN13: 9781501154560

https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/Cuba-(Winner-of-the-Pulitzer-Prize)/Ada-Ferrer/9781501154560

* Jan Servaes is editor of the 2020 Handbook on Communication for Development and Social Change (https://link.springer.com/referencework/10.1007/978-981-10-7035-8) and co-editor of SDG18 Communication for All, Volumes 1 & 2, 2023 (https://link.springer.com/book/9783031191411) [IDN-InDepthNews]

Collage: ‘Cuba. An American History’ (left) and the author, Ada Ferrer (right).

IDN is the flagship agency of the Non-profit International Press Syndicate