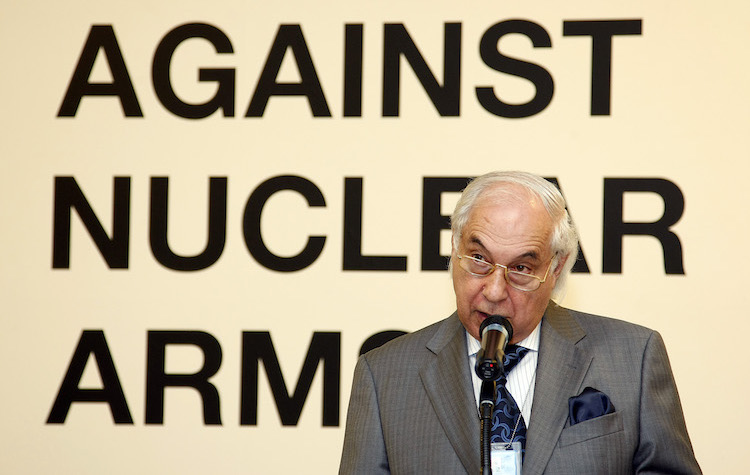

Viewpoint by Sergio Duarte

The writer is President of Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, and a former UN High Representative for Disarmament Affairs. He was president of the 2005 Nonproliferation Treaty Review Conference.

NEW YORK (IDN) – The advent of weapons of mass destruction, in particular the nuclear weapon, was the most dramatic factor of change in the strategic panorama since the Treaty of Westphalia established the basis of the current international order in 1648. During the following centuries, International Law was formulated and adapted continuously in an effort to accommodate changes in strategic realities and shifting security perceptions.

Since the start of the atomic age, fast technological advancement revealed increasing inconsistencies between International Law and the evolving strategic, tactical and logistical realities particularly in what regards the regulation of the use of force. There is a risk that the definition and practice of International Law become increasingly dependent on the decisions of the powerful and the arbitrary rule of the stronger.

The history of efforts to prevent proliferation and achieve the elimination of nuclear weapons provides important insights. These weapons started to proliferate on July 16, 1945, roughly three weeks after the adoption of the Charter of the United Nations. Their spread was partially contained through the Treaty on the Non-proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), jointly proposed at the Eighteen-Nation Disarmament Committee (ENDC) in 1966 by the two leading nuclear powers.

The NPT recognized five States as possessors of nuclear weapons but did not prevent four other countries to follow the same path. Tacit agreement that further proliferation could fatally disrupt the fragile balance of power in the world prompted measures taken by the General Assembly, the Security Council and other instances to curb perceived ambitions in that direction. In some cases, unilateral or group action was also taken.

The discussion of the draft NPT at the ENDC and its subsequent adoption by the General Assembly revealed deep divisions between nuclear and non-nuclear weapon States. Many obstacles had to be overcome during 1967 and 1968 but there was no final consensus on a draft treaty presented on March 11, 1968 by the delegations of the USA and the USSR.

This prompted its two co-Chairs (the representatives of the United States and the Soviet Union) to send on March 14, “on behalf of the Conference” a report[1] to the United Nations General Assembly. Annex I of that report contains a text that “includes changes incorporated on 11 March” by those two delegations[2] as well as a draft resolution, whose wording was revised at the I Committee of the General Assembly in an attempt to reconcile diverging views.

A final draft that also contained changes in the text of the treaty attached to it was accepted by the delegations of the USA and the USSR adopted on June 12 by the General Assembly as Resolution 2373 (XXII),2373. It endorsed the Treaty on the Non-proliferation of Nuclear Weapons and commended it to the signature of States.

The basic differences on the substance that had earlier prevented consensus at the ENDC explain the high number of abstentions in the vote of the resolution at the General Assembly.[3] In spite of that, the NPT gradually came to be subscribed by the near-totality of the International community and is now the most adhered to instrument in the field of arms control.

All but four among the member States of the United Nations are party to it. The NPT is now considered the cornerstone of the multilateral non-proliferation and disarmament regime. Even so, doubts about its implementation and perceptions of lack of compliance with key provisions continue to generate disagreement at the Review Conferences held at five-year intervals.

The five nuclear weapon States recognized under the NPT seem to interpret the Treaty as permitting the retention of their atomic arsenals for as long as they see fit and also as allowing for their “modernization”, that is, the increase of the range, speed, accuracy and destructive power of their weapons in an endless race for supremacy. The military doctrines of all nine possessors contemplate the use of these weapons in the circumstances that they deem adequate.

The conveniently convoluted language of article VI of the NPT provides ready-made arguments for the postponement of multilateral action. Significant sections of the international community show increasing concern at the longstanding deadlock at the Conference on Disarmament and at signs of growing mistrust and hostility between the two most heavily armed nations in history.

Recent exacerbation of tensions and aggressive behavior added to such concerns. Efforts by non-nuclear weapon States and NGOs resulted in the negotiation and adoption of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons leading to their elimination (TPNW) by 122 States in 2017. Nuclear weapon possessors and their allies, however, refused to participate in the negotiating process of the TPNW carried out under the aegis of the United Nations[4].

To date, 70 States have signed this Treaty and 22 have already ratified it. 50 ratifications are needed for it to enter into force. At the same time, new proposals to reinforce impediments to peaceful nuclear research and activities in non-nuclear weapon States keep cropping up, while those that possess such means of destruction continue to increase and diversify the power of their own weapons.

Over the decades since the end of World War II a number of multilateral and regional treaties and agreements on different aspects of nuclear armaments have been successfully concluded, all of them mainly aimed at curbing the proliferation of atomic weapons. Bilateral agreements between the United States and the URRS/Russian Federation to regulate the expansion of their arsenals were received with hope by international public opinion.

The number of nuclear weapons possessed by both countries declined from around 70.000 at the height of the Cold War to about 15.000 today. Unfortunately, however, further progress in agreed reductions seems to have stopped. So far, the two parties to the 2010 New START Treaty have not expressed willingness to extend it beyond the expiration date in 2021.

An ominous sign is the termination of important bilateral arms control agreements: the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty is no longer in force and the two parties to the 1987 Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) announced their intention to abandon it. Mutual accusations of incompliance have not been cooperatively addressed.

The Joint Common Plan of Action (JCPOA) agreed between Iran and the five nuclear weapon States recognized by the NPT, plus Germany, represented a major concerted effort to solve concerns about the nuclear program of the Islamic Republic. Unfortunately, the effectiveness of the JCPOA has been put into doubt and the agreement may not survive, at least in its present form.

These developments, together with the absence of initiatives for the negotiation of new disarmament instruments are evidence of an erosion of the confidence and credibility of the existing framework of international arrangements in the field of nuclear arms control. The NPT itself, which is considered the cornerstone of the international non-proliferation regime, may be negatively affected in consequence.

At the Conference on Disarmament (CD) in Geneva on February 25, 2019 United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres issued a stern warning: “Key components of the international arms control architecture are collapsing. New weapon technologies are intensifying risks in ways we do not understand and cannot even imagine.” He added: “States are seeking security not in the proven collective value of diplomacy and dialogue, but in developing and accumulating new weapons. We simply cannot afford to return to the unrestrained nuclear competition of the darkest days of the cold war.”

Proposals to start multilateral negotiations on specific measures of nuclear disarmament have been systematically rejected at the relevant organs of the United Nations by nuclear weapon States and their allies, under the argument that this would be “premature” and “counterproductive” in view of prevailing security realities. Non-nuclear States, for their part, contend that it is precisely because of such realities that those negotiations are necessary and urgent.

The possessors of nuclear arsenals profess willingness to keep their atomic arsenals “as long as nuclear weapons exist”, [5] a tautological, self-serving expression that denotes little willingness to engage in a serious negotiating effort. In fact, as long as nuclear weapons exist, the danger of their use by accident, miscalculation or design also exists. Moreover, unbridled competition for supremacy in armaments brings insecurity not only to those engaged in it, but also to the whole world. This should be reason enough for renewed efforts at their elimination.

Some of those States argue that a number of conditions would have to be met and that obstacles should be removed before nuclear disarmament can become possible. Many of the existing treaties and agreements in the field of arms control did not require the prior creation of favorable conditions defined by prospective parties. A number of them were negotiated and adopted in times of crisis and in spite of adverse circumstances, or rather because of them. Technical preparatory work contributed to a better understanding of the issues involved. Political obstacles were raised, identified and resolved during the negotiations themselves.

After all, the objective of arms control and disarmament negotiations is precisely to harmonize conflicting views and security interests taking into account existing strategic realities. In this respect, for instance, academics and scholars can assist ongoing negotiations by contributing to a better understanding of such realities and security concerns, as well as suggesting innovative ways to reconcile different positions and perceptions.

The proposal by a number of States to negotiate and adopt the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons leading to their elimination was made in the spirit of moving closer to the shared goal of a world free of nuclear weapons. Nuclear-armed powers shunned the whole effort. Some of their allies had a hard time explaining their positions to their own parliaments and public opinion.

Alleged obstacles or unfavorable conditions are often expedients to conceal lack of political will to engage in constructive multilateral action to rid the world of nuclear weapons. In their on-going pursuit of this paramount goal, the peoples of the world should not be made to wait for a proper alignment of stars or until the nuclear weapon States decide that the time to act finally has come.

A serious, determined effort to reduce tensions between the major nuclear powers would facilitate further bilateral agreements and could set in motion similar action by other possessors of nuclear arsenals and relevant players. There is no shortage of useful proposals in this regard. Such an undertaking requires mutual understanding, self-restraint and rational behavior from leaders as well as encouragement from civil society all over the world.

Progress toward a less contentious and collaborative climate would also stimulate the remainder of the international community to seek and support further agreements in the proper multilateral forums. As recognized in many international documents, disarmament and non-proliferation must proceed in tandem.

Past experience has taught mankind a number of lessons that must be heeded. Stability and security for all cannot be reached through egocentric, isolationist practices that only pursue the satisfaction of narrow national interests to the detriment of the larger interest of humanity. A system of international security based on the possession of weapons of mass destruction by a few is neither universal nor lasting.

A credible, solid system must be non-discriminatory and inclusive in order to provide reliable security assurances for all. Peace and security are public goods that belong to mankind as a whole. The necessary requirements for their benefits to be enjoyed by the international community are well known and do not need further study or refinement; they have only to be put into practice.

Public opinion has a vital role to play in this regard. Such requisites are: concerted, sustained efforts to lessen misunderstandings and tensions; constant exercise of responsibility and restraint, particularly by the most powerful; avoidance of threats and aggressive attitudes; adherence to established norms and principles of international law; respect for generally accepted standards of behavior among nations; and good faith compliance with obligations entered into. These guidelines must be followed by all, but nuclear weapon States are primarily responsible for leading action. [IDN-InDepthNews – 13 March 2019]

Photo: On 10 August 2009 Sergio Duarte, Under-Secretary-General for Disarmament Affairs, speaks at the opening of the exhibition “Against Nuclear Arms” at the UN Headquarters in New York. The exhibition portrayed the destruction caused by the A-bomb explosions in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, as well as decades of nuclear arms testing in Kazakhstan. Credit: UN Photo/Paulo Filgueiras

IDN is flagship agency of the International Press Syndicate.

facebook.com/IDN.GoingDeeper – twitter.com/InDepthNews

Send your comment: comment@indepthnews.colo.ba.be

Subscribe to IDN Newsletter: newsletter@indepthnews.colo.ba.be

[1] UN General Assembly, “Report of the Conference of the Eighteen-Nation Disarmament Committee”, A/7072, March 19, 1968.

[2] The Report also contains a draft resolution (Annex II); a listing of pertinent documents and verbatim records (Annex III); and proposals and working papers submitted by all Delegations in 1967 and 1968 (Annex IV). The Report states that “the views of individual delegations on the text of the treaty, to the extent they support or remain at variance with the text presented in Annex I, are recorded in the verbatim records”.

[3] General Assembly Resolution 2373 (XXII) was adopted by 79 votes in favor, four against and 21 abstentions.

[4] General Assembly resolution 71/258, adopted on December 23, 2017.

[5] https://wci.llnl.gov/science/stockpile-stewardship-program.”Make no mistake: As long as these weapons exist, the United States will maintain a safe, secure, and effective arsenal to deter any adversary, and guarantee that defense to our allies.” (Barack Obama, Prague speech, 2009).