By Jonathan Power*

LUND, Sweden, 23 May 2023 (IDN) — Do we, especially our politicians and media, focus more on threats than on opportunities, dwell on loses more than on gains, and learn more from past failures than from successes?

When we are children, we are frightened of bogeymen. When we are adults, we often inflate dangers.

When five years ago Steven Pinker published his book telling us how the number of battlefield deaths had gone dramatically down since World War 2 and pointed out how life had been transformed for poor people in the Third World because of immunization, contraception, disease eradication and widespread literacy, many were taken by surprise. They hadn’t realized they were living in a world, as Barack Obama once said, is the best time to be alive in human history. Yet the bits and pieces of this information had been around for a long time and over the last decade I’ve drawn on them in many of my columns. I’m not sure I convinced many people, so inbuilt is human pessimism!

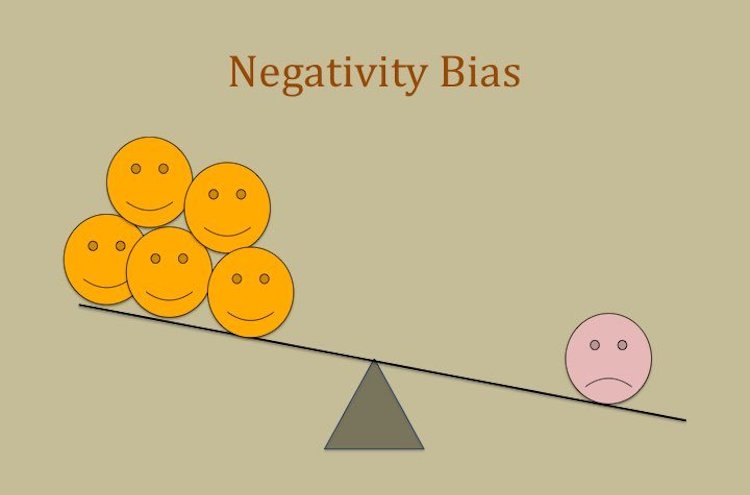

But the fact is that human beings have what Oxford professors Dominic Johnson and Dominic Tierney call a “negativity bias”— “A subconscious predisposition that humans exhibit whether or not they are aware of it”.

Their thesis explains a lot, especially in international relations—threat inflation, the outbreak and persistence of war, the neglect of opportunities for cooperation, and the prominence of failure in institutional memory and learning.

In modern times the worst example of this was the threat inflation launched by President George W. Bush in tandem with Prime Minister Tony Blair on the danger posed by Iraq’s Saddam Hussein. They exaggerated beyond all measure the likelihood that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction. The media didn’t do a good enough job and allowed the political leaders to get away with their misinformation campaign. The media too was victim to the human trait of negativity bias, but then it too often is. This led to an unnecessary invasion which caused immense suffering in Iraq, destabilized the whole region, led to the effectiveness of the nihilist Islamic terrorists in ISIS and stoked the Syrian war.

Why do people have a negative bias? Psychologists believe that the dominance of bad over good emerged as an adaptive trait to avoid lethal dangers in human evolutionary history.

At first glance, a systematic misperception of the world seems to be counterproductive. However, argue Johnson and Tierney, it is likely to have helped survival and reproductive success in tribal societies. They gave less weight to positive events which, while welcome, couldn’t compare with the consequences of negative events which might be matters of life and death.

A hair-trigger sensitivity to threat and the “fight or flight” response are widely evident across all mammals and can arise in humans via the release of adrenaline even before people perceive the source of the stimulus.

Scholars and journalists have identified many examples where the external peril was exaggerated. In the nineteenth century the British were obsessed with the possibility that Russia would invade India. In the 1960s much of the West came to believe in the American hype about the severity of the Soviet missile threat. These days we had Iraq and now Iran. Again, Russia is being seen as a predatory bear and, under US influence but with European connivance, the boundaries of NATO have been pushed right up to Russia’s borders- counterproductively. It has triggered Russian suspicions of Western intent, led to renewed Russian hostility, which eventually led to President Vladimir Putin over-reacting and invading Ukraine.

Evidence from neuroscience suggests that positive and negative information is processed in different parts of the brain. The unconscious mind is especially sensitive to threats. Negative information is received by the sensory thalamus and sent directly to the amygdala (the brain’s “threat centre”) which can trigger fear before the information enters conscious awareness. The effects can be long-lasting. To some extent this is beyond people’s control or even recognition.

Fortunately, today enough people are well enough educated, well read and experienced that they have the intelligence to counter innate negative impulses. Yet we know from the Korean War, Vietnam, the Iraq invasion and the expansion of NATO that this group is not large enough to be the dominant influence, either on politicians or on the media. The way most of the media works is that editors instinctively believe bad information has greater potency than equivalent good information.

Politicians and the media are often fixated on some historical precedent- for example the meeting between Hitler and Chamberlain at Munich. Appeasement is seen as a negative, a word to be thrown at the cautious, the wiser, the better informed of the lessons of history and those who are generally more positive. Yet in day-to-day life we all have to appease certain people- a parent, a spouse, a teacher, a doctor, an employer or a landlord to make life tolerable. Confrontation often doesn’t work. So it is with statecraft. A good example today is the hyping of the dangers posed by China.

Only we can stop the bad being stronger than the good.

Copyright: Jonathan Power.

* Jonathan Power was for 17 years a foreign affairs columnist and commentator for the International Herald Tribune, now the New York Times. He has also written dozens of columns for the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Boston Globe and the Los Angeles Times. He is the European who has appeared most on the opinion pages of these papers. [IDN-InDepthNews]

Image source: Caoimhe Whelan, IBCLC

Visit us on Facebook and Twitter.

IDN is the flagship agency of the Non-profit International Press Syndicate