By Dr. Palitha Kohona

The author is former Ambassador and Permanent Representative of Sri Lanka to the United Nations, and former Foreign Secretary. The following is Part 3 of the text of his keynote address delivered at Sri Lanka’s University of Peradeniya, Kandy, on 26 November 2018. – Click here for Part 1 and Part 2

COLOMBO (IDN-INPS) – As to whether Kandy could have managed to hold the British at bay for much longer or extract much more from the British in the negotiations at that point in history is highly debatable. My view is that for a leadership which was not much familiar with the momentous events shaping the future of the world and Britain emerging the undisputed super power of the world, the chiefs did remarkably well.

They knew what they wanted and had it reflected in the Convention while accepting the need for ridding the country of the detested Nayakkar king, who in their perception had become a tyrant, and replacing him with another foreigner from a distant land.

The British who concluded similar agreements elsewhere (Waitangi in New Zealand, in Bechanaland, etc), very quickly and perfidiously breached their solemn commitments. The breach of the Waitangi Treaty of 1840 was to result in the Maori Wars in 1845 which lasted till 1870. The results were roughly the same as those that followed the Kandyan uprising.

Thousands of Maoris were killed and dispossessed and over 16,000 square kilometres of their land confiscated. The story in the Southern African highlands was not too dissimilar and the struggle to recover the lands illegally possessed by the colonialists continues. The more recent gory history of the Kenyan highlands is no different and a sad indictment of the British.

Dissatisfaction with the British began to simmer almost immediately. The chiefs who signed the Convention in their enthusiasm to rid themselves of the Nayakkar King, and some to advance their own personal interests, began to entertain doubts about the wisdom of what they had done.

As records of their actual feelings are not available, it is difficult to gauge what they were actually going through. Perhaps self-doubt would have crept into their thinking. The proud history of resistance so easily sacrificed may have begun to torture their souls.

The British very quickly began to display their disregard for the Convention and the people’s expectations and this irked the leaders and the people even more. The people were used to being ruled by a king who moved with them at various social, cultural and religious occasions.

Hence, resentment grew as they felt that they were being neglected and unwanted in the course of day-to-day administration and governance by the strangers from distant Europe. But the troops of the Empire were now well established at strategic locations of the Kandyan Kingdom and the dissension that D’Oyly so carefully nurtured among the chiefs festered.

The aristocracy and the Buddhist priests were accustomed to receiving respect from persons who interacted with them. However, since the British rule, even a common British soldier would pass by a Kandyan chief paying hardly any attention as he would to anybody else. The disrespect demonstrated by the British annoyed the chiefs.

The people of Uwa were the first to raise the flag of defiance. It was a spontaneous uprising but the pent up emotions quickly fuelled a widespread conflagration. The chiefs provided the leadership.

The rebellion spreads

The first act of rebellion occurred in June 1816 when Madugalle Uda Gabada Nilame, secretly proposed to the chief priest the possible removal of the Sacred Tooth Relic from Kandy, thus removing one of the key symbols of power from British control.

Madugalle Nilame was dismissed from office and summarily dispatched to Colombo and then to Jaffna without being given the opportunity to even bid farewell to his family. His ‘walauwa’ was publicly torched on the governor’s orders, and his other possessions were confiscated and sold. Adding insult to injury, the sale proceeds went toward the establishment of a pension fund for British officers!

[Walauwa is the name given to a feudal/colonial manor house in Sri Lanka of a native headmen. It is also reference to the feudal social systems that existed during the colonial era.]

The immediate spark that set off the uprising was the appointment a Moor, Haji Marikkar, as Travala Madige Muhandiram of Wellassa, being rewarded for his services to the British, thereby undermining the authority of Millewa Dissawa of Uwa.

Malabaris were prohibited from entering the Kandyan provinces without obtaining prior permission, but when a pretender to the throne, Wilbawe, emerged, Sylvester Wilson, the Government Agent of Badulla, immediately sent the recently elevated Haji Mohandiram with a detachment to investigate. Haji Mohandiram was captured by Bootawe Rate Rala at Wellassa and, on Wilbawe’s orders, put to death.

Sylvester Wilson then proceeded from Badulla on 16 October 1817 to investigate with an armed escort of twenty-four Malay and Javanese soldiers under the command of Lieutenant Newman met with a similar fate.

The British Resident in Kandy John D’Oyly, dispatched Monarawila Keppetipola, the Dissawe of Uva, who was in Kandy, to Badulla with instructions to crush the rebels. But he went up to Alupotha and, following discussions, joined the rebels and was immediately recognized as its leader. His presence inflamed the rebellion. Keppitipola, displaying a dash of misplaced chivalry in the face of an insidious foe, returned all the arms and ammunition of the British.

As news spread of Kappetipola’s defection, Wariyapola Sumangala Thero of Asgiriya fled to Hanguranketa with the relic casket from the Sacred Temple of the Tooth, which resulted in the rebellion taking a more vigorous turn. There was a belief among the Sinhalese that whoever claimed the right to rule Sri Lanka must control the Tooth Relic. Now the Sacred Relic was with the rebels.

Reflecting the deep-seated feelings of the people and the chiefs, the rebellion began spilling rapidly into other dissawes.

But, unfortunately for the uprising, the chiefs, Molligoda, Ekneligoda, Mahawalatenne and Dolosvala did not lend their support. Perhaps, a critical factor in its eventual failure. Eknaligoda had already benefitted from the British crown for his role in capturing the King.

The spreading rebellion alarmed Brownrigg. He informed Earl Bathurst in London, that British prestige was at stake and that, if Britain lost, it would have far-reaching consequences for the Empire in India.

Accordingly, he requested the British Governor of Madras for reinforcements, which the Madras Government dispatched in the form of two battalions, one of European infantry and the other Sepoys of the Madras Native Infantry. The resources that could be drawn by the Empire to crush the rebellion were limitless. The tactics they employed were brutal, relentless and totally indiscriminate. The British Empire demonstrated that it would not tolerate rebellion.

Governor Brownrigg declared Marshall Law and issued a Proclamation on January 1, 1818 that seventeen leaders engaged in promoting rebellion and war against His Majesty’s Forces, were “Rebels, Outlaws and Enemies to the British.” Their lands and properties were confiscated by the Crown. The peasant farmers of these lands suffered as well.

A campaign of unprecedented ferocity and brutality

The British forces then launched a campaign of unprecedented ferocity and brutality, employing all the power and technology at their disposal and proceeded to crush the uprising.

The word scorched earth policy was invented in more recent times but the British, who would later preach human rights to the world, proceeded to implement this military approach without remorse. Burning, including rice crops, pillaging, destroying houses, fruit trees and domestic animals, devastating villages and killing and raping, they decimated the countryside.

Lieutenant J. MaClaine of the 73rd Regiment was in the habit of hanging captured prisoners whilst he took breakfast. For him, justice followed when the Kandyans shot him in an ambush. Lieutenant Colonel Hook used to hang anyone whom he suspected of being a rebel or a collaborator and anyone who appeared to be an adult male. Lieutenants Colonel Hook and Hardy concentrated their military activities in Wallapane and Badulla. Lieutenant Colonel Kelly and Major Macdonald engaged the rebels in Uva/Wellassa.

First Adigar Molligoda, for reasons that need to be discussed elsewhere, assisted the British and was handsomely rewarded by them.

In April 1818, Native Lieutenant Annan of the Ceylon Rifle Regiment (CRR) and twenty-nine of his men having penetrated into the rebel dominated countryside trapped Kohukumbure Rate Rala, (the 11th on the governor’s Wanted List) by pretending to desert to the rebels. By September 1818, Ellepola Adikaram surrendered to the British. Ellepola, the Dissawa of Viyaluwa, was beheaded at Bogambara on October 27,1818.

September 1818 saw the British gaining the upper hand whilst the rebel leaders showed signs of wavering. Governor. Brownrigg sensing an opportunity, promised leniency to the rebels and their leaders if they surrendered before the deadline of September 20, 1818.

The rice fields had been left fallow for several seasons and the villages had been devastated. There was widespread hardship amongst the villagers who had fled to the jungles and hills. One by one, the rebel chiefs and their men began surrendering with their weapons to take advantage of the amnesty offered by the governor.

With the rebellion collapsing, the valiant Keppetipola fled to Anuradhapura but was captured together with Pilama Talawa II on October 28,1818 by Lieutenent O’Neil assisted by Native Lieutenent Cader-Boyet of the CRR. Madugalle escaped. However, five days later, on November 02, 2018, Ensign Shootbraid captured Madugalle in the jungles of Elahera.

On the same day, the Sacred Tooth Relic fell into the hands of Shootbraid. “Its recovery had a manifest effect on all classes and its having fallen into British hands again by accident, demonstrated to the superstitious people of this country that it was the destiny of the British Nation to govern the Kandyan Kingdom,” wrote Governor Brownrigg to Earl Bathurst, in a triumphant dispatch.

Ehelepola Maha Nilame whose role in the uprising has received various interpretations over the years, but who was in British custody, was banished with several other chiefs to Mauritius by Brownrigg. It transpired later that Ehelepola was secretly providing guidance to the rebels.

Both Keppetipola and Madugalle were tried and sentenced to death. They were executed in Bogambara thus snuffing out the last flames of resistance of the Great Uprising. Keppetipola faced death in a manner that would inspire the nation for centuries to come. [IDN-InDepthNews – 08 December 2018]

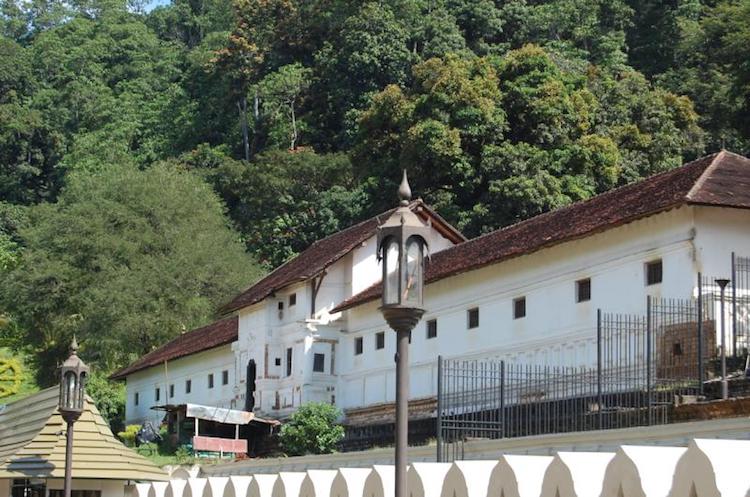

Photo: The Royal Palace of Kandy. The Royal Palace of Kandy

IDN is the flagship of International Press Syndicate.

facebook.com/IDN.GoingDeeper – twitter.com/InDepthNews