BUFFALO (IDN) – As its people of the year, Time magazine recently named the Silence Breakers — people who have spoken against sexual harassment and launched the hashtag #MeToo into an international phenomenon with more than seven million hits on social media.

Just before the announcement, more than 230 women who work in national security for the United States, from former ambassadors to military personnel, signed a public letter protesting sexual harassment, under the hashtag #MeTooNatSec.

The United Nations has not been immune to the problem, either, yet people seem far too afraid to publicly voice their stories, let alone hint at them, as the inner culture of the UN can be punishing and retaliatory. The extent of sexual harassment, however, was described as “pervasive,” with one woman describing the atmosphere as “Mad Men” territory.

Late in December, Secretary-General António Guterres issued a statement on sexual harassment, only days after this reporter asked for a comment from the UN about the phenomenon at the institution. In the statement, Guterres reiterated his commitment to a zero-tolerance policy across the UN system, saying that a chief-executive-board task force, led by Jan Beagle, who heads UN management, will submit a report on the problem by the spring.

Guterres is not the only UN leader speaking up. Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, the executive director of UN Women, was recently asked in an exclusive interview with PassBlue about the viral #MeToo campaign, which has rocked such major American industries as entertainment and media and many levels of politics. Mlambo-Ngcuka said the campaign was one of the best routes to advocacy, “especially because we’ve seen sanctions, we’re seeing powerful men being sanctioned, and losing their livelihood.”

“Violators,” she added, “they have been doing it because they can, because there are no consequences.”

As an example of how difficult it is for women to talk openly about sexual harassment at the UN, no one has used a #MeTooUN or even #MeToo + or any form of the word “diplomacy” on social media.

“I don’t have the figures, but I don’t think we are too different from other institutions,” Mlambo-Ngcuka said.

In response to efforts by former and current UN staff members and consultants who asked PassBlue to report on the phenomenon at the UN, nearly two dozen women agreed to speak off the record, asking for full confidentiality. These include veterans of the UN who worked there from the late 20th century to those in the first decade of their careers.

The women recounted stories of drunken advances from bosses and other men in jobs above their ranking, invitations to supposedly working dinners that led to awkward propositions, belittling and demeaning requests in front of colleagues and co-workers and, more seriously, economic and social repercussions for those who dared to say no or to rock the boat by reporting offenses.

One woman, who recently left her position at the UN to work for a Fortune 500 media company, recounted a supervisor who stood behind her to stroke her hair while she was working and who commented on her weight and appearance. His favorite method of harassment? Pinching her belly without warning.

“I used to call the bathroom on the 11th floor the cry-in station,” said the woman. “It was rare to go in there and not see a woman crying.”

In November, Guterres wrote a letter, co-signed by 14 leaders of UN staff unions and staff councils, to all UN personnel. In it, he acknowledged the breadth of harassing behavior at the world body. The letter also provided links to resources in the organization responsible for addressing sexual harassment: the UN Ombudsman and Mediation Service, the Ethics Office and the Staff Counsellor’s Office.

The letter read, in part: “We all have a duty and an obligation to create an environment that is welcoming to all, where everyone feels valued and where each colleague can perform at their best regardless of who they are or where they are from. . . . Key to this is understanding that harassment covers a wide range of actions; that this includes unpleasant and inappropriate comments or suggestive remarks; and that colleagues who receive such remarks may be offended, humiliated or discouraged, even if they don’t say so. Many staff, both victims and witnesses, accept this as an everyday reality.”

The letter indicates that those who signed it, including Guterres, recognize that sexual harassment at the UN is “an everyday reality.” The problem also stretches to country missions to the UN.

Of the 193 countries that compose the world body, 68 have no legal protections for women against sexual harassment in the workplace, and 46 have no laws offering legal protection to women against domestic violence, so if a woman is working for a country’s diplomatic mission in New York, she has no legal recourse to fight harassment.

Appropriate behavior is defined differently in different cultures, and in a multilateral setting such as the UN, this adds complexity to dealing with sexual harassment.

Women might remain silent on sexual harassment or gender-related misconduct out of cultural sensitivity, said Rachel Vogelstein in an interview. She is the Douglas Dillon senior fellow and director of the Women and Foreign Policy program at the Council on Foreign Relations and co-wrote a recent Forbes article, “When Sexual Harassment Is Legal.”

For some women who work for the UN and diplomatic missions this vulnerability is compounded by the fact that they are not just dependent on employment for their livelihood but also for their visas to stay in the US.

The majority of women who were interviewed for this article said that most or all of their female colleagues at the UN had experienced sexual harassment. All of the women said that the violations were not about sex or about attraction but about power. Some of the women called it “gender-based misconduct”; one woman even called it “gender belittling.”

Sexual harassment does not solely depend on trying to force a kiss or unwanted touching to have long-term ramifications on women and their careers. Women who were interviewed, for example, recounted debasing and degrading behavior, bullying and petty moves, like being given the wrong room for meetings or cut off when speaking in meetings.

“I was a 40-something-year-old married women, this wasn’t about attraction,” said one woman who was employed by the UN but is now with an outside organization that operates with the UN on projects.

Another woman, a retired veteran of the UN, suggested that the power that men wield, blatantly or more subtly, in the “insidiously patriarchal culture” of the UN can disrupt or completely destroy a woman’s career.

A third woman’s career at the UN was derailed by two men who outranked her on the pay scale, despite her proven expertise, because she rebuffed their advances and reported their inappropriate behavior.

Sexual harassment affects women not only emotionally and economically, but also, as a recent Harvard Business Review article argues, it can diminish the output of an organization by disregarding the “development of new ideas” from women.

“I think what we’re seeing in part is abuse of power,” Vogelstein said. Even within the US justice system, the onus is on the accuser to prove “severe and pervasive” harassment.

“One of the other pieces of this that is needed, in addition to greater levels of awareness, strong accountability and robust complaint mechanisms, and in addition to legal prohibition,” Vogelstein said, “is that, given that we are seeing clear abuse of power in so many of the reports, is addressing the abuse of power will level the economic inequities.”

As one woman interviewed for this article said, “Within the United Nations, the corporate structure favors men, it’s built on patriarchy.”

The promotional system of the UN has not changed since its founding in 1945, with two categories of employees: P for professionals and G for general, with the latter confined to all administrative and nonmanagerial tasks.

“It is a structure that is open to harassment, misogyny and gender-based pay inequalities,” the woman added. It is, she maintained, a system that can reduce women to possessions.

The zero-tolerance policy from Guterres, the ninth secretary-general (no woman has ever held the position) also extends to UN peacekeeping missions, which have been damaged reputation-wise in the last few years by many accounts of sexual allegations. The UN has begun to reckon with the breathtaking range of accusations, from rape of minors to impregnating women who live in the vicinity of peacekeeping missions.

The crisis is far from being resolved, say critics of the UN agenda to stop sex abuse and exploitation.

In the UN Secretariat, Guterres has made strides in bringing gender equality to upper levels of the UN in his first year of office, naming an equal number of women and men to top positions. While there may be parity in high echelons, the offices of middle management present a different environment.

A recurring theme among the women interviewed was the threat of abuse of power wielded by men over women in subordinate positions.

“We also routinely have to give advice to female interns on how to rebuff advances from male colleagues as that has happened a lot,” said a woman, who works in the Secretariat. Another woman pointed out that there is a recognized pattern of advances and retreats, with well-known offenders or serial violators.

One woman recounted how almost 30 years ago, an under secretary-general was having an affair with his own secretary, a much younger woman. An open secret, the affair was addressed only when the man’s wife made a scene at the office. To deal with the situation, the secretary-general at the time, Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, of Peru, fired the secretary; there were no job consequences for the under secretary-general.

In 1992, the UN instituted its first guidelines to define sexual harassment and created formal procedures for handling complaints, as a result of a sexual harassment case that had gone public. The process included informal mediation and led to dismissal or discipline, on paper at least.

Describing the case, The New York Times, which broke the story, said it illuminated what has been “widespread acceptance of sexual harassment and sex discrimination at the U.N.”

Ceceil Gross, who was interviewed for the Times article as an ex-president of the Group on Equal Rights for Women at the UN, said: “It’s never been politically wise for women here to say boo. Historically, when there were cries and whimpers heard, the women were fired.”

The 1992 case was not the first time that women at the UN protested their environment. On International Women’s Day in the 1980s, members of the UN women’s group wore all black, with black veils, “à la Jackie Kennedy in mourning,” said a woman by email.

“We were mourning the powerlessness of female UN staff,” she wrote. Impressively, at their press conference for the “mourning” event, a male union boss stood and spoke on their behalf. Still in their black gear, they met with the secretary-general then, Kurt Waldheim, to present their grievances. At the end of the meeting, according to one woman, Waldheim said he hoped they would all meet again next year and the women would be ” ‘wearing pink or blue or some other color.’ ” Waldheim never met with the women again, as he did not get another term for political reasons.

Veterans of the UN noted how in their careers, they were often they were mistaken for secretaries, simply because of their gender. So few women held professional positions in the UN in the late-20th century that personnel resolutions were set, mandating quotas to increase their presence in managerial and nonadministrative positions.

While not as wide a variance as in UN peacekeeping, where women constitute fewer than five percent of military personnel and 10 percent of police personnel, systematically the UN has not reached total gender parity, despite progress in uppermost jobs.

According to figures published by the UN this year, an entry-level or early-career cohort is usually at parity. But when this cohort reaches the upper levels of management, it will probably be only 27 percent women, if it stays true to current trends. So the gender gap widens with the pay grade.

The Office of the Focal Points for Women is part of the UN System Coordination Division of UN Women — a mouthful reflecting its broad scope, which includes focal points for women in the UN Secretariat and gender focal points from agencies across the UN system. The focal points for women are focused on achieving Guterres’s goal of moving the UN toward professional parity.

“The progress [in achieving gender parity] has been slow and uneven,” Katja Pehrman, who is the focal point for women in the UN system at UN Women, wrote by email, “with an average of 0.6 percentage points per year for the UN system as a whole.” Pehrman suggested that the UN has reached a tipping point, and is considering such things as flexible work schedules and unconscious-bias training.

Sexual harassment at the UN can also be taken up through an internal panel of volunteers that investigates or hears allegations of a case, called peer probes (or ombudsman). The Office of Internal Oversight Services, the UN’s legal arm, is another avenue. Both resources have been called “a hit and miss system” by some women.

For example, one person reported being told by the human resources department, when trying to detail instances of her boss’s harassment, that she had to file the complaint with her boss. Another woman recalled pleading with her female supervisor and human resources not to be moved under a known offender, only to be told, “We’ll take care of you.” She left the UN after a year of working for the man.

“I felt that the women in human resources were listening, with looks of familiarity and empathy,” she said. “But at the end of the day, it’s a UN lawyer in a UN court, the system is internal and entirely stacked against the accuser.”

One woman who holds a high position in the Secretariat said, “The backlash for reporting abuse and misconduct within the diplomatic world or UN system is enormous, and can quickly end a career for a victim.”

Even when confronting male offenders, women’s remarks had to be couched in a tentative, jovial manner. The woman whose supervisor used to stroke her hair told of how another woman tried to intervene by cautioning the stroker in an insider manner that he should be careful, lest human resources get involved.

Part of the challenge for the UN may be that no woman has led it from the top. In 2016, a record number of female candidates, seven, put their names in the proverbial hat to become secretary-general for the 2017-2022 term, but no woman came close to obtaining enough votes from the UN Security Council to land the job.

Yet any woman who gets to the top of the UN in its multicultural structure will have had to play the game, said one woman, and the game does not include protecting other women.

The culture is so entrenched, she said, not even a female secretary-general could change it. [IDN-InDepthNews – 13 January 2018]

[This article was updated.]

This article first appeared on PassBlue and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

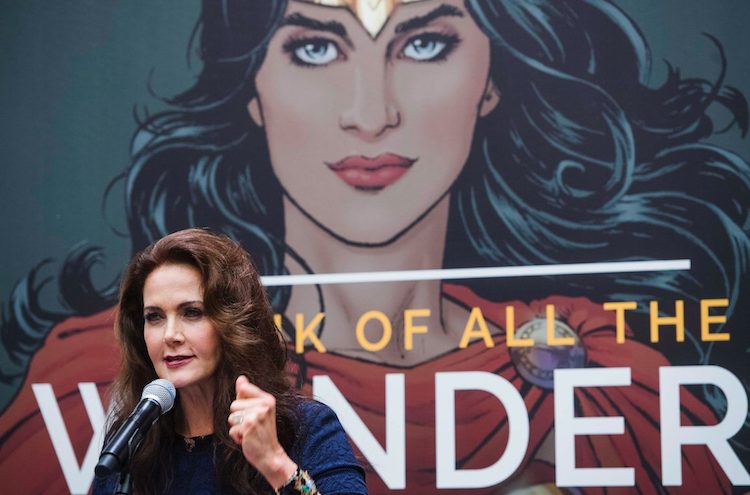

Photo: Lynda Carter, star of the TV show “Wonder Woman” from 1975 to 1979, at the launch of a campaign for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. The designation of Wonder Woman as ambassador for the empowerment of women and girls in 2016 was vehemently rejected by UN staff members and outside the UN as a sexist symbol. The campaign was dropped soon after protests were raised. Credit: AMANDA VOISARD/UN PHOTO

IDN is flagship agency of the International Press Syndicate.

facebook.com/IDN.GoingDeeper – twitter.com/InDepthNews