By Jan Servaes

LAGOS, Portugal | 8 June 2024 (IDN) — We all know that when Christopher Columbus landed in ‘America’ in 1492, he thought it was India. Much less is known about the Portuguese navigator Vasco Da Gama who was the first to reach the real India in 1498.

This ‘discovery’ was due to the sponsored expeditions by the Portuguese Prince Henrique/Henry (1394-1460), the third son of John/João I, king of Portugal, and Philippa of Lancaster, the daughter of John of Gaunt of England.

His sister, Isabella, was the third wife of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy and Count of Flanders, consolidating Portuguese interests in the Low Countries. Their son was Charles the Bold, the last Valois duke of Burgundy. Isabella’s family ties with the English royal family were also useful in ending the Flemish-English trade war (1436-1439). In 1439, the Duchess acted as head of the Burgundian delegation that negotiated the cloth trade, and the colonization of the Azores by a group of Flemish people was also a result of her involvement.

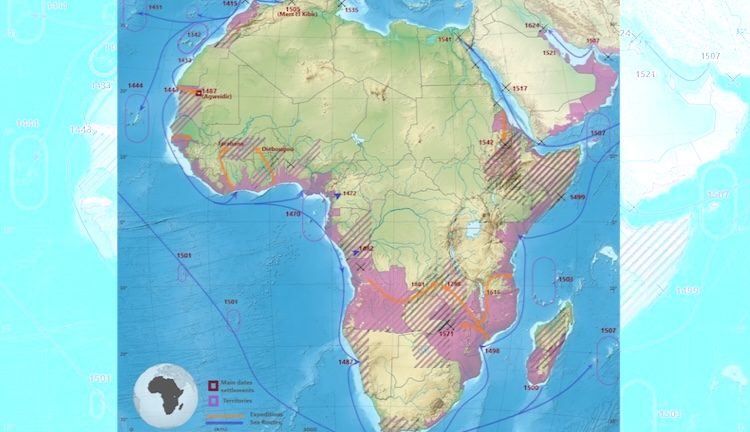

Henrique was the first European to methodically explore Africa and the oceanic route to the Indies as early as the mid-1420s. From his home in the Algarve in southern Portugal, he sought opportunities to participate in the West African trade, especially the trade in gold and enslaved persons, and to establish potentially profitable colonies on under-exploited islands, the most successful of which he helped establish in Madeira.

Nicknamed the Navigator, Henry paved the way for the modern world. He did not undertake sea voyages himself, but he financed and planned these expeditions to expand Portugal’s territory and wealth and to spread Christianity. His actions led to the European Age of Discovery, and also initiated the process of European colonization, capitalism, and ultimately the transatlantic slave trade.

This was partly possible thanks to the collaboration with Flemish carpenters and maritime craftsmanship, which his sister Isabella introduced to him. They helped the Portuguese develop better seaworthy ships for circumnavigating Cape Bojador and the Cape of Good Hope.

That is the essence of the monograph by João Paulo Oliveira e Costa, history professor at the Universidade Nova de Lisboa, which I discovered during a recent trip to Portugal. As the title of this monograph indicates, Henry was “the forerunner of globalization.”

The analysis is in the same line as Howard French’s book already discussed here.

João I

Until 1249, parts of Portugal, and most of what is now Spain, were a caliphate known as Al-Andalus. Muslim Berbers (Moors) from North Africa invaded much of the Iberian Peninsula in the early eighth century and conquered it from the Christian Visigoths, a Germanic people.

Islamic rule was not the only obstacle to Portugal’s independence. In 1095, Portugal seceded from the Kingdom of Galicia. Alfonso Henriques, son of Count Henry of Burgundy, proclaimed himself King of Portugal in 1139. The Algarve was conquered from the Moors in 1249 and Lisbon became the capital in 1255. Portugal’s borders have remained virtually unchanged since then.

During the reign of King João I, Henry’s father, the Portuguese defeated the Castilians in a war for the throne (1385) and entered into a political alliance with England (by the Treaty of Windsor in 1386). To this day, Portugal remains culturally more oriented towards England than neighboring Spain.

John’s long struggle with Castile and the need to form a new aristocracy caused serious financial problems, but he rallied his people around his throne and gained a reputation as a prudent leader and an astute statesman. Thanks in part to Queen Philippa, influenced by English traditions, John’s court also became known as a center of culture.

Ceuta 1415

In 1415, Portugal invaded Ceuta, a fortified city in Morocco. The justification for the invasion, which was seen as a military and religious crusade, was that the port city was a haven for pirates. João I placed his three sons in charge of the expedition, as a challenge to earn their knighthood.

In addition to pirates, Ceuta was also the place with a vibrant trade. Henry learned of trade between North African Muslims and West Africans and Indians. This new knowledge about Africa and Asia aroused his interest.

As a devout Christian, he wanted to defeat Muslims and spread Christianity in a permanent holy war. But his planned expeditions required a large investment for a relatively poor country. The country’s thriving merchant class, which also included a prominent Jewish community, became the financing power for Henry’s costly projects. The Catholic Church also offered support.Henry brought together sailors, ship designers, astronomers, mathematicians, navigators and cartographers at Sagres, his base on the southern coast of Portugal. This also included Jews, Muslims and Flemish. Much of their geographical knowledge was based on the work of the ancient geographer Ptolemy and the Arab scholars who continued his work.

Many of the instruments that became essential for navigation on the open sea were adaptations of instruments used, sometimes by people from different cultures, for other tasks, such as the compass, the hourglass, the quadrant and the astrolabe.

The caravel, a small maneuverable ship that could sail against the wind, was perfected in this way thanks to Flemish craftsmanship.

Past Cape Bojador

After all, one of the major problems that Henry faced in his competition with the Spanish to find a suitable sea route to the Indies was the rough waters off Cape Bojador. Located in what is now Western Sahara (a disputed territory held by Morocco since 1979), the current in this part of the coast moves south, making sailing to Europe difficult. The bigger obstacle may have been superstition, as the cape’s original name in Arabic is Abu Khaṭar (ابو خطر), meaning ‘father of danger’.

Among the expeditions that Henry sponsored, Portugal colonized islands off the coast of West Africa, including the largely inhabited Canary Islands, as well as the uninhabited islands of the Azores and Madeira.

In 1434, a navigable route around Cape Bojador was found by the Portuguese sailor Gil Eanes. This was considered a major breakthrough for European explorers and traders heading to Africa and later to India. A first attempt by Eanes in 1433 resulted in failure. But at the command of Prince Henry the Navigator, Eanes tried a second time and proved successful.

But Henry needed money to keep his expeditions going. The prince wanted access to West African gold. West Africans, however, retained control of local gold reserves, only willing to trade mainly gold dust with the Portuguese during Henry’s lifetime.

Slavery

Therefore, the economic impetus shifted to another resource: enslaved people. The Portuguese began systematically raiding settlements on the island of Arguin to kidnap local residents. These Africans were enslaved and brought to Lisbon. In 1448, the Portuguese built a fort, warehouse and trading station on the island, located off the coast of what is now Mauritania.

In the early 1650s, enslaved Africans were forced to build and farm sugar plantations in Madeira. Plantation economies focused on a single cash crop to make profits. This plantation system was repeated in other Portuguese colonies. African prisoners were taken from the mainland and the Cape Verde Islands, off the coast of Senegal, where they were forced to work.

Global colonization

By the time of Henry’s death, in 1460, the Portuguese had reached what is now Sierra Leone. However, many of Henry’s ambitions were also shared by his successors. The Portuguese founded colonies along the west and east coasts of Africa.

In the years that followed, the Portuguese created trading ports as far away as Japan. Portuguese navigators also ventured to India, Malacca, Thailand and kingdoms along the Indian Ocean.

Beginning in the 16th century, the Portuguese established sugar plantations in Brazil, using enslaved workers shipped across the Atlantic Ocean from the west coast of Africa. With its large-scale forced transport of captured Africans to the Americas, Portugal, along with rival Spain, created what would become the transatlantic slave trade. This involved all European colonists, including the British, Belgians, Dutch, French and Spanish. However, the starting point, both historically and geographically, was Portugal.

After all, while Henry opened up trade and connected different peoples and cultures, his colonization efforts led to some of humanity’s greatest atrocities. Historically, colonization has resulted in a loss of resources, land, life, religion, culture and autonomy for the indigenous people who were colonized.

This attitude became evident with the signing of the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1495, which divided colonization claims in the Western Hemisphere between Spain and Portugal without regard or consultation with the indigenous nations and people groups living there.

The blind spot

“The modern world would not exist without slavery,” Howard French already stated in his ‘Born in Blackness‘.

Yet it is striking how absent this history remains in contemporary Portugal. The national school curriculum, museums and tourist infrastructure essentially amount to a grandiose display of the country’s 15th to 17th century ‘discoveries’ in Africa, Asia and the Americas, and a selective memory of its 20th century colonial exploits in Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde, São Tomé and Principe, Goa, Macau and East Timor.

In Lagos, the port where the first enslaved Africans disembarked from Portuguese ships in 1444, the only acknowledgment of this history in the city’s popular, touristy center is a hard-to-find little museum called the ‘Slave Market’, which opened in 2016 in collaboration with UNESCO.

Al Jazeera, which focuses extensively on this issue, offers a good overview of the problems that Portugal still struggles with today in terms of culture and racism.

Collecting data on race and ethnicity is still illegal under the current Portuguese Constitution. This clause in the constitution, intended to make up for the explicit racism of the Portuguese colonial dictatorship that was overthrown in 1974, has become a major sticking point for anti-racism movements in Portugal. It means that there is no official information about the population numbers of ethnic minorities. The lack of these data make it difficult for activists to argue for greater investment in public services for Afro-descendant and other racialized communities, or to prove the existence of racial bias and structural inequality.

Portugal’s increasingly assertive and politically engaged black population, now in its second or even third generation, is today at the forefront of a Portuguese society pushing for a more nuanced and complicated version of history to finally be told. This Movimento Negro also draws more attention to the ongoing legacy of structural racism—in terms of police brutality, equal access to housing and education, and political representation.

But, says sociologist Cristina Roldão: “From people in authority and from the man in the street you still hear the idea that Portuguese colonialism was different, benevolent and gentle. That idea is still common, but it is far from reality.”

Reference: João Paulo Oliveira e Costa, Henry, The forerunner of globalization, Faro, Portugal: Direcção-Geral da Cultura do Algarve, 79pp. (ISBN 978-989-99521-0-2) [IDN-InDepthNews]

Map of Purple Portuguese Empire in Africa, from 1342 to 1801. Routes, settlements, expeditions and Battles. Dates = Age of Discovery