Viewpoint by Michele Nobile*

This is the fourth of a four-part series. Click here for Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3.

ROME (IDN) – Since 2004-2005, the CCP has set itself the task of “building a harmonious society”. The internal harmony of China presupposes the discipline of farmers and the working class within the paternalistic dictatorship of the single party. No longer totalitarian as in the time of Mao – and how could it be otherwise when becoming rich is the glory of “socialism”, transnational societies are courted, Confucius is a model of wisdom and capitalists are no longer demons to beat?

But still it is a dictatorship of a single party over the people and wage earners. In the face of this, the references to “characteristics” and national sovereignty are fig leaves that cover the shame.

The new Head of State and party Xi Jinping has specified the goal of achieving – between 2020 and 2035 – the condition of xiaokang shehui, of a moderately prosperous society, without poor. Already used by Deng, the formula can be traced back directly to the Confucian canon of the Book of Rites and is full of associated meanings, which go beyond that of economic well-being.

Inferior and subsequent to datong, the mythical golden age of ideal harmony, here it is interesting to highlight that xiaokang shehui presupposes that filial piety (xiao) does not extend to the whole of society and that individual interest is pursued, albeit within the framework of respect for rituals and roles in a hierarchical society governed by wise and lawful rulers.

Chinese tradition and Adam Smith seem to merge into the rhetoric of a harmonious society, but the Sons of Heaven and the high mandarins of the current “celestial” bureaucracy are aware of the internal contradictions and dangers to social and political stability that they entail.

The memory of the 1989 crisis has certainly not disappeared from the memory of CCP leaders.

Since the end of the 1990s, labour conflicts, citizens’ protests and social movements of various kinds have increased considerably, and have been dealt with through a combination, which varies according to the case, of repression, opinion campaigns aimed at neutralising the impact – in the exemplary cases cited in party propaganda manuals also through the use of internet and modern methods of investigation and marketing – and channelling into individual legal procedures.

Furthermore, the Great Recession, the effects of which on world trade have not yet ended, has shown how risky it is to rely on exports to guarantee the dynamism of the Chinese economy. So the regime must at the same time prevent social mobilisation – inequality among classes and privileges and corruption among Party-State cadres are even greater than thirty years ago – and reckon with the uncertainty of foreign demand.

For social stabilisation, the regime has set itself the objectives of creating a consumerist and politically integrated middle class and of reducing the number of people in extreme poverty. In the first decade of this century, this gave rise to a gradual adjustment of rhetoric and social policies, accelerated by the consequences of the international economic crisis that began in 2008.

It must be considered that until a few years ago most of the rural population was in practice excluded from pension and health care systems; and this is true by definition and for all types of social insurance also for workers in the informal economy (which includes but is not limited to workers and migrant workers from the countryside) who are by far the largest part of China’s workforce, and who are also prevented from resorting to procedures in the field of labour law.

The first important correction of line was the downsizing of the tax burden placed on farmers in 2004, which in the 1990s had become unbearable, a disparagement for the Party and also the cause of criminal-type behaviour by village cadres; in 2007, the minimum guaranteed income programme (dibao) was extended to the countrysides. Then, and especially with Xi Jinping’s rise to power in 2013, regulations to extend the coverage of public services and social welfare have been increased.

However, these measures come after thirty years of “reforms” that have dismantled the relationship between state-owned enterprises and public services for urban workers, increased private spending on health and education, discriminated against rural areas, structured a social security system that has been unequal and regressive in favour of – in order of importance – Party cadres, state officials, employees of state enterprises and the population with urban hukou.

The problem is that while coverage of the population as regards pensions and health has been extended, the value of this coverage is extremely uneven according to employment, hukou and province, and it is inadequate precisely for the groups most in need. The social security system is fragmented and subject to fiscal constraints because the responsibility of social policy falls on local administrations: the central government has started to contribute, but local differences in spending capacity remain considerable.

On the whole, the reform of social policy is a very late and limited operation of rationalisation of the reproduction of the labour force, which extends the legal framework of rights but has a very unequal economic value. Moreover, rather than aiming to grant social rights to workers and immigrants working in the city, reform of the hukou system is motivated by the desire to create a land market in order to extend cities and industrial and commercial projects through exchange between the land rights of rural families and urban hukou.

Another obstacle on the path of harmony is corruption of officials. Campaigns against the corrupt and exemplary punishment are recurrent, but these are limited to individual cases and scandals that could not be managed in silence. On the other hand, the systemic nature of corruption and cronyism of good relations – guangxi – cannot be touched because it is rooted in the synergy between the dictatorship and the extent of economic interests managed directly and indirectly by the party-state bureaucracy.

The building of harmony is a source of agonising dilemmas for administrators in the peripheries. Because of the uniqueness of the Chinese one-party system, the career of cadres depends on a score for objectives. However, especially in the poorer regions, it is difficult to reconcile budget constraints, investment levels, extension of social security coverage, respect for environmental regulations and conflict neutralisation in localities of their jurisdiction.

As often happens, the more there is a focus on harmony and the needs of the people, the more this is indicative of the danger of social conflict given the scale of socioeconomic imbalances, power whose ideological legitimacy is nothing short of fragile and corruption that is taken for granted.

The Confucian imperial tradition which the modernisers of “socialism with Chinese characteristics” recall is two thousand years old – of enormous importance but not the most sympathetic of Chinese civilisations. However the development of capitalism does not produce a harmonious society, it produces economic contradictions and social conflict.

Ultimately, the “socialist” element of “socialism with Chinese characteristics” tautologically comes down to the fact that the ruling Party calls itself “communist”: it is a case of ideology in the purest sense of the term, “opium for the people” at home and for the gullible abroad. Since it is now too far removed from the collectivist ideology of the Maoist era and the Party cadres are the first to get rich, nothing remains for legitimisation of the power of this “socialism” but paternalistic statism and nationalism.

Through a sort of parable in a contribution to One China, Many Paths, Wang Yi has expressed the path of the people of China from the time of Mao to that of reforms or, in his words, from status to contract as follows:

“There is something akin to slavery in this. A slave is originally the property of a slave-owner. The slave-owner pays no wage to the slave but allows him a little plot on which to grow his food, to keep him alive while he toils on the plantation, and supplies him with a hut, clothing and some medical care. One day the slave-owner suddenly announces: ‘you are free – we shall contractualise our relationship’, cancels all the necessities he has been providing to the slave and deprives him of his plot of land. If the former slave complains, we criticise his dependence on the slave-owner and remark that he does not understand the meaning of freedom”.

Wang Yi then describes some of the consequences of contractualisation for slaves released in the late twentieth century: the sacking of tens of millions of workers – in breach of contracts signed a few years earlier – the concentration of wealth, the inexistence of a pension system up to 1995, the high cost of medical care, and so on. And he rightly observes:

“On the one hand, the government pursues legal reform to shed, step by step, its historical responsibilities to workers. On the other, it is also increasing taxation to improve ‘profits’ (…) In other words, as it shifts from status to contract, the government still keeps to the totalitarian policy of expropriating from labourers as much as possible of their surplus in order to concentrate resources on developing a state-directed economy”.

It is to the capitalist sector of state ownership, at that time in a phase of restructuring, that reference is being made here, but the argument is still valid. However, despite the harsh criticism, Wang Yi appeals to the Party’s sense of responsibility in establishing “the great contract of a constitutional system, without which all other contracts are vulnerable”, alluding to democratisation from within the regime.

Almost twenty years have gone by since that hope was expressed, and forty have passed since the turning point in 1978: “contractualisation” has made further great strides in China, but workers continue to be denied the freedom to strike and of independent organisation, censorship continues to operate and political dissent persecuted.

Meanwhile, the most recent amendments to the Constitution are abolition of the limit of two presidential terms and the constitutionalisation of Xi Jinping-thought, so that the dictatorship of a single party formally returns being complete with concentration of power indefinitely in the hands of a single man and his clique of associates. And, even more so after the reorganisation and grand-style revival of the state capitalist sector, it is not plausible that the Party-State is willing to abandon control of the economic enterprises that make the private fortune of its cadres.

The conclusion is that the ruling caste of the “communist” Party-State has made its capitalist “revolution” but cannot give the Chinese people elementary “bourgeois” freedoms: the interdependence between the dictatorship and the accumulation of capital is stronger than ever.

The Chinese people will have to conquer political freedom and social liberation with their own forces. As always, as everywhere in the world.

* Michele Nobile has published essays and books on the contradiction between capitalism and the environment (Goods-Nature and Ecosocialism, 1993), on the theory and history of imperialism (Imperialism. The Real Face of Globalisation, 2006), and on the transformations of the state and economic policy in the crisis (Capitalism and Post-Democracy. Economics and Politics in the Systemic Crisis, 2012). He is one of the founders of the international association Utopia Rossa (Red Utopia) which published the full version of this article in Italian under the title ‘Sul “Socialismo con Caractteristiche Cinesi”, Ovvero del Capitalismo Realmente Esistente in Cina’. Translated by Phil Harris. [IDN-InDepthNews – 09 October 2018]

Part 1 > On ‘Socialism with Chinese Characteristics’ – or Problem of Epochal Social Transformation

Part 2 > On ‘Socialism with Chinese Characteristics’ – or Mask of Capitalism

Part 3 > On “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics” – or Ideological Mess and Reality

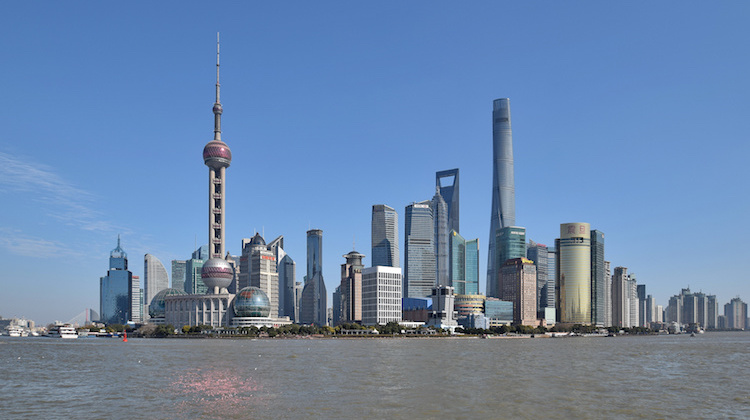

Photo: Skyline of Lujiazui, Pudong New Area, Shanghai (2016). Xi Jinping has specified the goal of achieving – between 2020 and 2035 – the condition of xiaokang shehui, of a moderately prosperous society, without poor. CC BY-SA 2.5

IDN is the flagship agency of the International Press Syndicate

Facebook.com/IDN.GoingDeeper – twitter.com/InDepthNews