By Yossef Ben-Meir*

MARRAKECH, Morocco | 16 October 2025 (IDN) — So much of world poverty today can be accounted for by the gap between vision, intention, and the codification of policies to support people’s own driven change and growth juxtaposed against unsatisfactory implementation, the lack of application, and a deepening stratification. The disappointment, very real, is made more heavy because of how needless the lack of fulfillment really is.

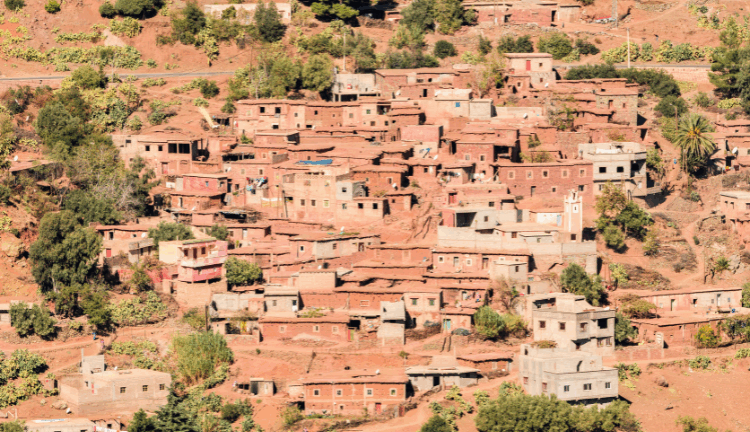

In Morocco, in rural and urban places, opportunities abound. The national frameworks for shared sustainable growth are thoughtful and well-articulated. People cherish their origins in every part of the Kingdom, and they, like most everyone everywhere, just want to work and work so hard when the chance is at hand.

I never found reason to blame communities or groups of people for the poverty conditions. Society’s and historical circumstances combined with inconsistent application of established programs and budgets account for failures to bridge the “two speeds” of development that are found, as His Majesty King Mohammed IV recently described, which generations in the nation have yet to overcome.

Drawing from His Majesty’s vision, Morocco’s youth and rural communities and neighborhoods can determine and achieve the development projects that respond directly to their specific needs. At the same time, this can inspire countries of the world who face their own desperation and fragility.

Projects that create growth and endure, and that are experienced directly by the communities of people who need them most, must be determined by them. There is no more widely-identified lesson learned than this: people commit their energy and time to maintain development that they have identified, manage, and receive benefits from. How, though, is this achieved?

Across cultures and experiences, and certainly over decades in Morocco, communities’ own determination of local socioeconomic and environmental projects does not necessarily ensure that those initiatives resonate directly with their self-described interests. This is especially true when they, like most people in our world, have never been asked their vision prior to the fortunate circumstance of engaging in inclusive community dialogue to plan actions for their development.

How do they respond when they have not yet introspectively considered their hearts’ goals in life or built the confidence to voice and pursue them? How do they react when they feel, in their local setting, the social controls that come with tradition or the roles they are expected to play based on their age, gender, and demographic?

Morocco champions ministerial and national strategies for community-driven projects in agriculture, education, health, business development, and other essential areas. It needs to vastly invest in empowerment—personal and collective development-envisioning programs—so that the local communities of the nation (beginning with women and youth) cultivate the clarity of project objectives, backed by determination, to understand and achieve their own project dreams. Open forums that don’t first build a sense of personal direction and self-analysis of individuality, social relationships, work outlook, and other key areas of life result into a disconnect between the projects that emerge and what people actually want.

Empowerment before project planning aligns people’s sincere will with defined project types and goals. These shared growth movements necessitate trained facilitators who build their skills through a learning-by-doing experience.

Youth are an incredibly promising demographic to perform this agency role. Clearly, they have immense desire. They seek a productive, acknowledged outlet to improve their society, and they are essential for locally driven processes that achieve employment and a better world. Young people are also pained. They are organizing and calling out. In Morocco is seen the exasperation of youths’ innate calling being widely denied.

Where and how do we train our youth so that they may be the initiators of community action to define and pursue projects to meet their priority needs? The established youth centers in all parts of the nation generally represent enormous possibilities but are severely under-resourced and understaffed. These locations should be empowerment training grounds where young people not only pursue their own self and community development but also build their capacities as assistants of these processes, ones who create self and group exploration experiences.

All public universities in Morocco have established strategies to provide applied experiences for students involving community engagement, but here again, the resources to effectively achieve this necessity are absent. A significant proportion of public university students are from rural places. With their key skills in advancing locally-designed development and with support, they would fully embrace the opportunity to return to their countryside and create initiatives with other young people and with communities as a whole.

Vital to all of this is the training of teachers, professors, youth center directors and staff, civil association members, members of municipal councils, and administerial personnel who engage with local people in these techniques of inspiring and guiding individuals and groups toward empowerment. We cannot expect university students and participants at youth centers to know or even dedicate themselves in this way without guidance from the professionals responsible for these institutions.

With a determined focus and resources for personal and community action planning and self-belief-building workshops, we gain clarity about the most important projects that the people seek to implement. Even as empowerment workshops are completely central for sustainable development, they cannot replace the absolutely essential need for project fulfillment. The people’s initiatives must become real to generate jobs, food security, economic and environmental resiliency, water access and management, artisanal and agricultural cooperatives, family literacy, cultural heritage preservation, school infrastructure, and other priorities.

Of the multiple excellently formulated policies for sustainable development that have been codified since the ascendancy of His Majesty the King to the throne in 1999, the Roadmap of decentralization is certainly among the most creative and has the most potential toward forming a prosperous future. Even as it is embraced by law, its practical manifestation is commonly considered inadequate.

A primary reason for its delay in impacting people at the local level is that most communities have not experienced their own empowerment, and inclusive, participatory dialogue and planning for the future is not their typical modus operandi. When further decision making authority is transferred to already socially stratified locations, decentralization can actually entrench those imbalances even further where those who have privilege and capital gain even more influence. Decentralization thus follows when communities collectively act, jointly design, and engage in the decision making to accomplish shared personal and group-related goals.

Morocco’s decentralization is regionalization, building the administrative capacity within its 12 regional capitals with the outcome of not enough strengthening of local cooperatives that are formed and managed by the people. The delegation component of decentralization which harnesses the community dimension needs tangible strengthening. It’s difficult to imagine the highly centralized public administration effectively decentralizing itself. The rate of this necessary decentralizing process is not outpacing the ability for the people to help meet their own vital needs.

A ministry of decentralization, not handed to the ruling party of the government but under direct accountability to His Majesty the King as the nation’s final arbiter, may be what is needed to ensure the deconcentration component of Morocco’s decentralization. This intersectoral collaboration at all administrative tiers complies with the other elements of Morocco’s decentralization Roadmap to ultimately fulfill the local people’s own development projects.

I imagine no one has greater frustration and disappointment than the King of Morocco, who has envisioned and established every principle guide needed for community-propelled opportunity. He also established the priority of mountainous regions and oases that cover 30 percent of the country, where economic, educational, and health difficulties are comparatively the greatest. But what indication have we that governments will actually overcome the systemic divide as the majority of youth and women in rural places bear the heaviest of poverty’s burden?

I have passed years of my life in the mountains of Morocco, dedicated to the people’s development. The most effective strategies for widespread development fulfillment can only come by the commitment of time to be impressed upon by their own derived pathway forward. Once empowered growth visions are built by the people, creating proposals and business plans is then a side by side affair, if the level of literacy skills are not currently existing locally to create the written plans that financial donors require. Infrastructural and community-action replication is faster-moving when the most distant villages in the furthest municipalities from provincial capitals are the first engaged (rather than working from closest to city centers outward, which is more typically the case).

But are public servants broadly enough so dedicated and do they have the means to travel as widely as critically required to co-create communities’ proposals to help secure the resources they need to launch their project dreams? I have seen amazingly stalwart and truly admirable public officials across agencies, and hope in my heart for their continued good rise. The opening of the catalyst and facilitator function in jurisdictions of the Kingdom is there for youth to assume, and they can know it and have the strengthened ability to fulfill it with applied learning programs of national importance.

In regards to cost, consider this as an example and frame of reference. There are 1,538 municipalities in Morocco, and 1,282 are rural. Having assisted rural communities in all 12 regions in their planning of the projects they want most of all, has revealed that water infrastructure for drinking and recycling for irrigation; capacity building with civil and cooperative groups in production activities, organizational management, and training of trainers for scale; mountain terracing for food production and stemming erosion; resilient fruit and forestry tree and medicine plant agriculture; product processing and other value-added activities such as carbon offset credits; school infrastructure; and historic preservation that enhances livelihoods are among the most common priority initiatives decided by the people.

An average cost to implement these projects enabled by trained youth and other facilitators of empowerment and community planning is approximately $3 million USD per rural municipality. In other words, $4 billion dedicated in this decentralized methodology could not only eradicate rural poverty and enable youth, women, and farming communities who have experienced the severest inequality in Morocco to achieve their best future where they are from, but it could also give new meaning of responsibility for time to come on what it means to be hosting the world for global sporting, cultural, and other humanity-unifying events.

Morocco can show all nations that the divide between aspiration and reality can be overcome and that the gap of sadness and the distressing loss of people’s potential can finally be no more.

*Dr. Yossef Ben-Meir is President of the High Atlas Foundation in Morocco. [IDN-InDepthNews]