By Morgane Wirtz*

This year, hundreds of migrants and asylum seekers settled in Tunisia have packed up to risk their lives again in Libya. For them, “It is better to die for something than to live for nothing”.

BRUSSELS (IDN) – It is a large white house with blue shutters in Al-Maharas, a small town in central Tunisia. The ground is immaculate. The rooms are empty. Through the open windows, we hear the sea. The scent of seaweed and sea salt tickles our nostrils. If we close our eyes, it feels like we are on vacation. If we close our eyes.

If we open them, we see, gathered on two mattresses placed on the floor, these seven inquisitive faces, these bodies riddled with scars, these looks, laden with suffering, but also, if we look further, hope.

‘Europe refused us’

“We have many problems, too many problems,” Aaron** keeps repeating. Like his roommates, he arrived early May on a boat loaded with 47 people, mostly Eritreans. They had embarked in Zuwara, northern Libya, hoping to reach Europe. But due to lack of fuel and after three days at sea, they had to resolve to dock in Tunisia, pulling their boat for several hundred metres.

“We called Alarm Phone [the hotline for people in distress at sea]. A helicopter flew overhead several times. They saw us, but they didn’t want to help us … They refused us. Maybe because of coronavirus …,” says Aaron.

12,000 dollars in ransom

Eritrea is often referred to as “African North Korea”. In hundreds of thousands, its citizens risk their lives to cross the border and flee the authoritarian regime and indefinite national service. Their migratory path is fraught with pitfalls.

With difficulty, Amanuel** agrees to tell a few snippets of his story. After negotiating in Sudan for passage to Libya, he was kidnapped in the Sahara and sold to a human trafficker. “He asked me for 6,000 dollars. When I had finished paying, he promised to take me across the Mediterranean Sea. But he was lying. He was going to sell me again.”

It was in Bani Walid, a stronghold of human trafficking in northwest Libya, that the young man landed. “When we got there, we couldn’t see anything. They had blindfolded our eyes. Once inside, they closed the door. No way to run away,” Amanuel recalls. He concentrates on remembering the three rooms in this place: one for women, one for Somalis, one for Eritreans.

The new trafficker asked the same amount as the first: 6,000 dollars. Again. To obtain it, the victims are beaten, often on the phone with their families present so that they hear the screams and, out of pity and fear, end up putting together the requested sum. “People died in this place,” continues Michel. “The owner is very cruel. He kills people, by guns or by electric shocks. I have seen people die in front of my eyes because they did not have enough to pay the ransom,” he says.

“We are all stressed out. Once we get here, how can we continue? How to continue our lives? Our future? Our programme?” adds Aaron. To free their children from the clutches of human traffickers, parents go into debt and sell their homes.

These young Eritreans housed in Al-Maharas do not sleep at night. The ghosts of Libya and the rest of their journey haunt their minds as this eternal question: how to reimburse their parents and restore their dignity?

Neglected

Al-Maharas’s pretty empty house cannot meet the financial hopes of asylum seekers. Firstly, the Tunisian Council for Refugees (CTR), a partner of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) can only accommodate them for a period of three months. Secondly, they receive a voucher of 30 dinars (9 euro) a week, as only financial and food assistance. The aim is to encourage asylum seekers to be independent.

“We have a language problem, we don’t know how to communicate in Arabic,” explains Amanuel. Here, only Jonah speaks English, everyone else communicates mainly in Tigrigna.

Asylum seekers also complain about the lack of answers to their health questions. “That person, you see?” Aaron asks, pointing to one of his mattress neighbours. How not to see? The man looks like a living skeleton. We can guess the bones of his skull piercing his face. “He went to the hospital with the CTR [Tunisian Refugee Council], but we still haven’t received the results. It’s been over two weeks. We want to know what he has. If he has TB, we have to isolate him,” says Aaron. The same morning the CTR of Sfax affirmed that “all the people who have health difficulties are taken in charge and their case is closely followed.”

Many of the African asylum seekers in Tunisia share the claims and concerns of the Eritreans of Al-Maharas. Between January and April 2020, more than one hundred crossed the border back to Libya to retake the risks in reaching Europe. Since the end of the lockdown, this situation has become commonplace. “It’s really unfortunate,” reacts Chiara Cavalcanti, UNHCR communication officer in Tunisia. “We are raising awareness of the danger of returning to Libya. But we also know that in Tunisia the options are extremely limited,” she adds.

“For the majority of people, their only hope is that by applying for asylum they will be automatically resettled in Europe,” explains Krimi Abderrazek, CTR project manager. This programme, which allows the most vulnerable refugees to be brought in by flight and settled in Europe or North America, for example, depends mainly on the goodwill of the hosting countries. However, according to the CTR, in Tunisia only about fifteen people are resettled a year.

Tunisia does not have a national asylum law, European countries have very limited quotas for resettlement, and UNHCR’s budgets depend on donors, which themselves are currently limited due to the coronavirus pandemic. Krimi Abderrazek says and insists: the CTR is doing its best to meet the needs of asylum seekers despite the situation.

“Die for something”

“It’s better to die for something than to live for nothing,” says Aaron, one of the Eritrean refugees, when he says he is considering returning to Libya very soon. A few days later, he no longer answers the phone. This is common when migrants go to Libya. They may be hiding, in prison, in the hands of human traffickers, or in the sea… Everything is imaginable. You just have to wait and hope for the best.

“People choose Libya over Tunisia. Why? Is this place worse than Libya?” complains Bisrat**, another Eritrean, who has been living here since 2018. “NGOs are doing something to say that they are doing something. But on the ground, it is not enough,” he explains, before adding:” Here, you feel like a prisoner in a wild area.”

Aaron and his friends made it. They are now in Europe. Most of them are in detention in Malta. After his quarantine, Aaron is the only one who can go out. “I am partially happy,” he says, before adding, bitterly: “My father is really glad that I am in Europe… But I left a lot of my friends back in the hell of Libya.” [IDN-InDepthNews – 02 September 2020]

* Morgan Wirtz is researcher and PhD student with Tilburg University. The research project is funded by ZonMw, the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development. She is also a researcher for Europe External Programme with Africa.

** Names have been changed.

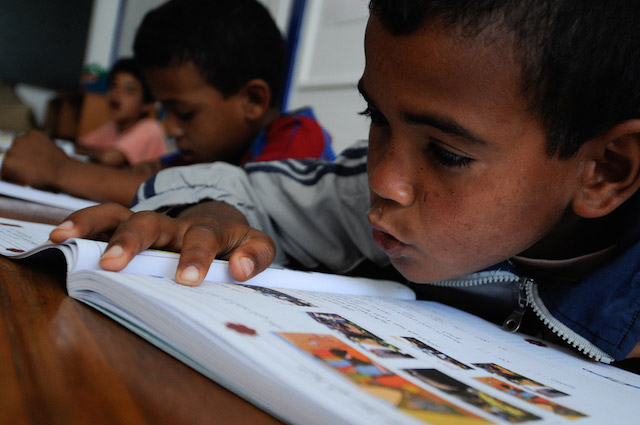

Photo: Eritrean asylum seekers in Tunisia, in search of a better life ©MorganeWirtz

IDN is flagship agency of the International Press Syndicate.

Visit us on Facebook and Twitter.

This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. You are free to share, remix, tweak and build upon it non-commercially.