By Jonathan Power*

LUND, Sweden, 7 March 2023 (IDN) — “The lives of all politicians end in failure”. So said Enoch Powell, a maverick former cabinet minister in the British government.

Of recent US presidents, Jimmy Carter has not been alone in being considered “a failure”.

Think of George W. Bush (Iraq war). Bill Clinton (Monica Lewinsky and a wasted last term). George H.W. Bush (messing up the economy and laying the foundation along with Clinton for the great economic crash of 2007). Ronald Reagan (missing the chance with Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev to create the nuclear-free world that he offered). Richard Nixon (Firing up the Vietnam War and having to resign in disgrace). Then there was Barack Obama who missed the opportunity to forge a great rapprochement with Russia. As for Donald Trump…

Back to Jimmy Carter who, according to the man himself, appears to be dying.

I had a tangential responsibility for his election. I went to interview him in Atlanta when he was governor of Georgia. I spent the best part of the afternoon and early evening with him—being offered only a coke for dinner!

He took me into his bedroom to see his small library of books. He plucked down a copy of a sort of biography cum manifesto he had written. “I’m a bit short of copies”, he said. “Can you mail it back once you have read it?” I did. I was foolish not to have asked him to autograph it since shortly after, unexpectedly, he won the fight to become president.

I also put my foot in it. I am a good friend of Andrew Young, who was Martin Luther King’s chief of staff. We got to know each other when I worked on the staff of Dr King and his “End the Slums” campaign in Chicago. Young was also from Atlanta. He was then a congressman and later Carter appointed him Ambassador to the UN.

I told Carter about our friendship. Carter asked, “What does he think of me?” I replied, “Not much”.

At a reception shortly after Carter accosted Young about this remark which led to Young explaining why he felt like that. They had a number of meetings after that cleared the air. Young was an important player in national politics.

Soon after Carter announced, he was going to run for president. Young agreed to join his team. According to Carter, Young won the election for him by getting out the black southern vote. Shortly after Carter had won, I visited Young and he said, laughing, “Look what you have done with your big mouth—elected the president of the United States”!

Carter gave Young a carte blanche to run America’s African policy, not least the effort to end white rule in Rhodesia and South Africa. Carter was persuaded by Young to ask Congress to introduce tight economic sanctions against South Africa.

In a policy forged by Zbigniew Brzezinski, the president’s national security advisor, who I interviewed at length many times, the US secretly shipped modern weapons, including the deadly Stinger missiles, to support the successful effort by the Afghanis to drive the army of the Soviet Union out of Afghanistan.

If that was a victory, what followed was not. It led to civil war, with the best-armed faction, the Taliban, winning out. Later they gave a home and base to Al Qaeda, which added Saudi Arabian arms and money to build up its strength. From here, Al Qaeda prepared for 9/11.

The US, under George W. Bush, decided because of 9/11 to bomb Afghanistan in an attempt to squash Al-Qaeda. They succeeded, although Al-Qaeda, having moved to Pakistan, morphed into ISIS.

The US and NATO went on fighting the Taliban until last year, when they finally withdrew in August of 2021, defeated. That was living out of Carter’s legacy. The whole effort by seven successive presidents beginning with Carter was a cause for disgrace.

But fortunately, there is far more to Carter than that.

Carter, a highly religious man who taught in his local Sunday school whenever he could get home, felt that God had created the US in part “to set an example for the rest of the world”. Human rights were to be the centrepiece of his foreign policy, he kept saying. In practice, it wasn’t so straightforward.

As Hodding Carter, the State Department’s spokesman at that time once observed, his human rights policy was “ambiguous, ambivalent and ambidextrous”. Hodding Carter’s wife, Patricia Derian, who was the assistant secretary for human rights, was often frustrated by the lack of support from her superiors.

Carter’s new policy was most effective in the Western hemisphere. After he was defeated for a second term, he visited Argentina and was swamped by crowds who thanked him for helping undermine the military regime which had imprisoned and tortured a wide range of opposition activists.

The Catholic Church in Argentina, of which the present pope was an important member, was largely silent, unlike its counterparts in Chile and Brazil where there were also repressive military regimes.

Thus, the role that Carter played was an unprecedentedly successful, non-violent, intervention. It brought results. The regime was weakened and eventually toppled. A similar impact was made in several other Latin American countries. Arms sales were cut off and a number of countries were economically squeezed.

Carter did raise human rights to a new level of political potency. Certainly, in Latin America, but also in Indonesia, India, Myanmar, East Timor and South Korea, he emboldened religious, labour and liberal groups to be more openly critical of their regimes. Carter told the South Korean military regime that he would pull out all US troops if they executed Kim Dae-jung, the opposition leader, who went on to become president.

More than this, Carter’s human rights crusade provided both then and today a yardstick against which the foreign policy of Western nations came to be judged, even when Carter partly turned his back on his earlier commitment.

One serious flaw was Carter’s obsession with defeating communism in the Soviet Union. He mislaid his sense of even-handedness. Even in his final speech at the Democratic Party Convention, he singled out the USSR as a human rights pariah while not mentioning the rest of the world.

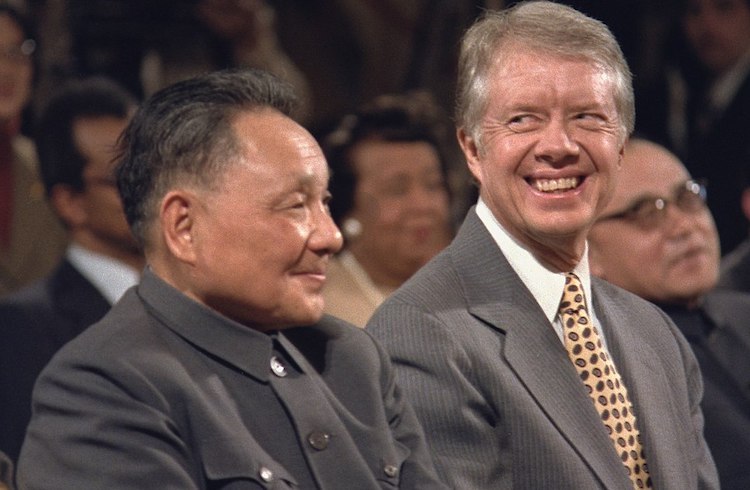

When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan to impose a Marxist regime, it spurred Carter to orientate the US towards China. Carter, who had vowed during his campaign for the presidency he wouldn’t “ass-kiss” the Chinese, paid no heed to the jailing of Democracy Wall activists in 1979. Carter was intent on concluding the formal normalization of relations with China. Carter looked the other way when the important Chinese dissident Wei Jingsheng was sentenced to fifteen years’ imprisonment. Yet at more or less the same time, Carter was lambasting Moscow for sending Soviet dissident Anatol Scharansky to prison.

Carter’s worst bit of dual thinking—you can call it hypocrisy—was his policy towards Cambodia. When the US withdrew from Vietnam, Cambodia under its villainous leader Pol Pot became not just a thorn in the flesh of Vietnam, it killed an estimated 1.7 million of its own people in a massive genocide—the so-called “Killing Fields”, (the title of a superb movie). In 1978 Carter declared Cambodia “the worst violator of human rights in the world”.

But Carter, anxious not to cross China, which he was wooing, said little more. China was Pol Pot’s friend. “I encouraged the Chinese to support Pol Pot,” Zbigniew Brzezinski told the New York Times. He was wedded to the old Henry Kissinger formula of “playing the China card” against the Soviet Union.

As Jonathan Alter has written in Foreign Policy magazine, “it got worse”. He explained: The US supported Pol Pot’s claim to the Cambodian seat in the United Nations. Pol Pot’s flag flew outside the UN building. All the European nations, except Sweden, joined the US in its recognition of the Pol Pot government.

Many diplomatic and journalistic observers have argued that China would not have broken off its rapprochement with the US if Carter had decided not to go along with supporting the Pol Pot government. China had too much at stake with the US to allow a tail to wag the dog. Indeed, when the Vietnamese finally toppled Pol Pot, China stood by.

Carter’s legacy is mixed. His supporters say that his compromises were matched by his successes, particularly in the USSR. Victor Havel, the dissident playwright who later became the president of the Czech Republic, said that not only did Carter inspire him in prison, but he also undermined the “self-confidence” of the Soviet bloc. The self-confidence of Eastern Europe’s human rights organizations did grow.

The former Soviet ambassador to Washington, Anatoly Dobrynin, wrote in his memoires that Carter’s human rights policies “played a significant role” in the Soviet Union, loosening its grip at home and in Eastern Europe. Once liberalization was underway, Dobrynin concluded, it couldn’t be controlled.

The image of the US as an upholder of human rights is badly tarnished after the tenure of George W. Bush and Donald Trump. There are many faults to be remedied at home before other countries will take the US as seriously as they used to.

True, thanks to Carter’s convictions, human rights issue does run through the bloodstream of the Democratic Party. But before getting caught up in challenging and criticizing others as he does regularly, the present president, Joe Biden, should put his own American house in order. At home the list of constant human rights abuses is a long one. American democracy is not in a healthy state.

Carter’s life is not ending in failure. Despite his mistakes in Afghanistan and vis a vis the Soviet Union, we have much to thank him for, compared with other presidents. Biden will have to work hard to measure up to him.

[Jimmy Carter, now 98, recently entered hospice care designed to make patients comfortable at the end of life. Read more in Washington Post.]

* Jonathan Power was for 17 years a foreign affairs columnist and commentator for the International Herald Tribune, now the New York Times. He has also written dozens of columns for the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Boston Globe and the Los Angeles Times. He is the European who has appeared most on the opinion pages of these papers. [IDN-InDepthNews]

Why not order Jonathan Power’s books? “Like Water on Stone – The Story of Amnesty International” Published by Penguin and “Conundrums of Humanity” published by Nijoff and Amazon.

Image: Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping and Jimmy Carter in January 1979 during Sino-American signing ceremony in Washington. Source: Wikipedia [Read also Visit by Deng Xiaoping to the United States]

Visit us on Facebook and Twitter.

IDN is the flagship agency of the Non-profit International Press Syndicate.

Note for editor: Copyright Jonathan Power