Viewpoint by Manish Uprety F.R.A.S. and Jainendra Karn *

NEW DELHI (IDN) – Dealing with numbers can take a toll and might make one seek fulfillment in other spheres. No wonder the most influential poet of the last Century penned The Waste Land in 1922 when he was dutifully employed with the foreign transactions department of Lloyd’s, an austere English bank in London.

Another case that one can think of is of Peter Bone, an accountant by training and Conservative party Member of Parliament in England from Wellingborough and Rushden who in November 2018 found glee when he made no bones about how and where the Republic of India should spend its resources. The latter reminds one of the famous aphorism Par Updesh Kushal Bahutere.

With immense challenges to meet in the sphere of development especially in developing countries, and many policy options and opinions available, one is but tempted to explore the issue a bit more diligently as one has finite resources and limited avenues to generate them.

In 2015, world leaders agreed to the Global Goals for Sustainable Development, a set of 17 goals for a better world by 2030. These goals aim to end poverty, fight inequality and address the urgency of climate change among others, and seek the participation of governments, businesses, civil society and the general public to work together to build a better future for everyone.

It seems like the typical case of old wine with a new label. Following the Millennium Summit of the United Nations in 2000 and the adoption of the United Nations Millennium Declaration, all 191 United Nations member states at the time, and at least 22 international organizations, committed to help achieve the eight UN Millennium Development Goals by the year 2015. Each goal had specific targets, and dates for achieving those targets but unfortunately could not be met.

Critics of the MDGs complained of a lack of analysis and justification behind the chosen objectives, and the difficulty or lack of measurements for some goals and uneven progress, among others. Anyway through Resolution 70/1 of the United Nations General Assembly on September 25, 2015, that has the 2030 Development Agenda titled “Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,” the eight UN MDGs transformed into seventeen SDGs and 169 targets.

However, the learning from MDGs experience was also typical in many ways especially in terms of the utilisation of development aid. It is interesting to note that the aid from the developed countries to secure the MDGs, more than half went for debt relief, and most of the remainder toward disaster relief and military aid, rather than to further development.

During the launch of the Human Development Report (HDR) for 2014 by the United Nations which for the first time considered the concepts of vulnerability and resilience in assessing human development progress, Helen Clarke, Administrator of the UNDP had noted that while every society is vulnerable to risk, some suffer far less harm and recover more quickly than others when adversity strikes.

A society is all about its experiences. Colonization by the European countries had an extremely deleterious effect on societies of Africa and Asia. Its pernicious impact can be witnessed even in the contemporary times and judged by the development indices.

When the SDGs were announced in 2015, it was understandable that success on global goal no. 1—eradication of extreme poverty—depended on Africa’s performance. However, recent forecasts from the United Nations and the World Bank suggest that Africa is not going to make it.

Why has poverty in Africa stayed so stubbornly high despite record economic growth and what role has its historical experience to play would be an interesting study?

According to the World Bank report, three main reasons:

(i) less of Africa’s growth translates into poverty reduction because of high initial poverty, including low asset levels and limited access to public services, which prevent households from taking advantage of opportunities;

(ii) Africa’s increasing reliance on natural resources for income growth rather than agricultural – and rural development excludes the 85 percent of the poor population living in rural areas; and

(iii) Africa’s high fertility and resulting high population growth mean that even high growth translates into less income per person—a point too often ignored in discussions on the sub-continent and in Washington.

It is not difficult to infer that high initial poverty and reliance on natural resources and lack of agricultural development have a direct link to European colonization.

Regarding Asia, the famed British economic historian Angus Maddison had calculated that in 1600, of the world GDP (GDP being computed in 1990 dollars and in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms) total share of China and India was 51.4%, with China accounting for 29% and India 22.4% of world GDP.

A hundred years later, China’s GDP had fallen but India’s went up to 24.4% of world output. By 1820, however, India’s share had fallen to 16.1%. By 1870, it further went down to 12.2%.

Noted economist Utsa Patnaik has calculated that over roughly 200 years, the East India Company and the British Raj siphoned out at least GBP 9.2 Trillion (or USD 44.6 Trillion; since the exchange rate was USD 4.8 per GBP sterling during much of the colonial period) from India.

In the colonial era, most of India’s sizeable foreign exchange earnings went straight to London—severely hampering the country’s ability to import machinery and technology in order to embark on a modernisation path similar to what Japan did in the 1870s.

Harvard educated renowned statistician-economist and Indian Member of Parliament Dr. Subarmanian Swamy who has worked with Nobel laureates like Simon Kuznets and Paul Samuelson calculates the amount looted by the British from India to be USD 71 Trillion.

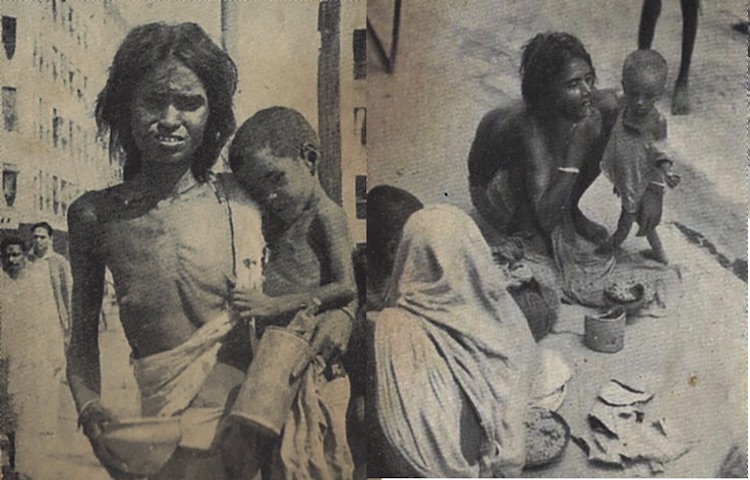

Under the British Raj, India suffered countless famines. The worst hit was Bengal in 1770, followed by severe ones in 1783, 1866, 1873, 1892, 1897 and lastly 1943-44. Earlier when famines had hit the country, indigenous rulers were quick with useful responses to avert major disasters. But not only a ruthless economic agenda but also a total lack of empathy for native citizens was a prominent trait of the European colonization.

The famine of 1770 alone killed approximately 10 million people, millions more than the Jewish holocaust during the Second World War or the Belgian genocide in the Congo. It wiped out one-third the population of Bengal. John Fiske, in his book The Unseen World, wrote that the famine of 1770 in Bengal was far deadlier than the Black Plague that terrorised Europe in the fourteenth century.

We should all be concerned, but what can be done? The recent World Bank study, Accelerating Poverty Reduction in Africa, offers governments and stakeholders both new suggestions as well as new takes on old recommendations. It should also have considered reparations to the colonized countries by the European colonizers, and the important role reparations can play to accelerate the process of development and secure the UN Global Goals.

In 2013 Caribbean Heads of Governments established the Caricom Reparations Commission (CRC) with a mandate to prepare the case for reparatory justice for the region’s indigenous and African descendant communities who are the victims of Crimes against Humanity (CAH) in the forms of genocide, slavery, slave trading, and racial apartheid.

The CRC asserts that victims and descendants of these CAH have a legal right to reparatory justice, and that those who committed these crimes, and who have been enriched by the proceeds of these crimes, have a reparatory case to answer.

One can only speculate what a developing country like India currently ranked at number 130 in HDI with its 46.6 million children who are stunted because of malnutrition can achieve if it manages to secure USD 71 Trillion from Britain as reparation.

Monetary inputs have the capability to initiate virtuous economic and development processes in a society. A good example of it is the 1948 Marshall Plan or the European Recovery Program. More than USD 13 billion under the Marshall Plan helped to facilitate the recovery of Europe’s national economies and helped build a ‘new Europe’ with a political economy that was based on open markets and free trade, rather than protectionism and self-interest. It was a stimulus that set off a chain of events leading to a range of accomplishments. However, aid is always conditional where terms are dictated by the donor.

Therefore the CRC sets a wonderful precedent to establish the moral, ethical and legal case for the payment of Reparations by the Governments of all the former colonial powers and the relevant institutions of those countries, to the nations that were colonized.

In fact, it is far a better alternative than the same old clarion call to “mobilize resources for the poor” made to the Asian and African governments to raise taxes as a share of GDP or the strings that come attached with overseas aid.

It’s November 2019. Would Right Honourable Peter Bone and others including international institutions help set a continuing historical wrong right, and kindly pay heed to make reparations play a mainstreamed role to eradicate poverty and secure UN Global Goals, and pave way for a more just and humane world?

* Manish Uprety F.R.A.S. is an ex-diplomat and Jainendra Karn is a senior leader of the Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP). [IDN-InDepthNews – 02 November 2019]

Photo: Mother in shreds of clothing with child begging on the streets of Calcutta during the Bengal famine of 1943 (left), and a family on the sidewalk in Calcutta during the Bengal famine of 1943 (right). Source: Wikipedia

IDN is flagship agency of the International Press Syndicate.

facebook.com/IDN.GoingDeeper – twitter.com/InDepthNews