By Roberto Massari*

This is the first of a nine-part series.

BOLSENA, Italy (IDN) – In June 2018, I was invited to make a presentation on the relationship between Che Guevara and Karl Marx at the International Conference on Karl Marx: Life, Ideas, Influence. A Critical Examination on the Bicentenary, organised by the Asian Development Research Institute (ADRI) in Patna (Bihar), India.

What follows is the fruit of my work to that end and is conceived along the lines of a documentary film structure:

FIRST HALF

Ouverture

Scene 1 [La Paz, 1996]

Scene 2 [Dar es Salaam, 1965]

Flashback

Scene 3 [Lima, 1952]

Scene 4 [Rome, 1969]

INTERVAL

Scene 5 [Sierra Maestra, 1956-58]

SECOND HALF

Orthodoxy Story

Scene 6 [from Havana to Moscow, 1959-63]

Heresy Story:

Scene 7 [from Moscow to Havana, 1963-65]

Marxist Story:

Scene 8 [Prague, 1966]

Fade-out

Scene 9 [Vallegrande, 9 October 2017]

FIRST HALF

OUVERTURE: Scene 1 [La Paz, 1996]

At 10:30 on Tuesday, October 1, 1996, five visibly excited people took the lift down the 30 metres to the Banco Central de Bolivia basement. Three were journalists, one a photographer and the fifth a researcher of Che Guevara: for the first time, the Bolivian government had given them free access to the ‘A-73’ safe-deposit box in which the original copy of Che’s Bolivian diary was and is still kept.

However, the box contained other very important material, as Carlos Soria Galvarro Terán (1944) – my great friend, companion in research and leading scholar of Che in Bolivia [at the time together with Humberto Vázquez Viaña (1937-2013)] – was to discover with great emotion.

In fact, they found: a) the original copy in Spanish of Pombo’s diary, which was believed to have disappeared after its translation into English; b) evaluation forms of all the guerrilla members; c) the red loose-leaf notebook with diary pages from 7 November to 31 December 1966 (in addition to notes and drafts of press releases); and d) the German leatherette agenda with diary pages from 1 January to 7 October 1967.

But it is exactly at the end of this agenda, in the five final pages, that Carlos made the most disturbing discovery for we researchers into Che and where this reflection of mine on the relationship between Guevara and Marx starts: these five pages contained a list of 109 book titles (15 of which marked with a red cross), divided by months (to be reduced in quantity) from November 1966 to September 1967.

This was completely new documentation that showed the deep interest Che had continued to nurture for study and theoretical elaboration up to the last hours of his life, despite finding himself in desperate circumstances and knowing that he was by then destined to (military) defeat.

Carlos let me have the photo of the list and I published it in colour (to highlight the red crosses) in Volume 2 of Che Guevara. Quaderni della Fondazione “Ernesto Che Guevara” – Che Guevara: Notebooks of the “Che Guevara” Foundation [CQGF] published by Massari Editore.

The titles cited covered a wide range of themes and did not seem to refer to a particular bibliographic scheme. We scholars thought that they could be divided roughly into six categories: 1) philosophy and science; 2) political and military doctrine; 3) Latin American history and society; 4) Bolivian history, society and anthropology; 5) novels and world fiction; and 6) working tools such as dictionaries, statistical repertoires and medical issues.

The first group is the one of interest here and could include – besides N. Machiavelli (The Prince and other political writings), G.W.F. Hegel (Phenomenology of Spirit) and L. Morgan (Ancient society) – works on Marxism or of Marxist inspiration such as the following:

C.D.H. Cole, Political Organisation;

- Croce, [with the title used in Spanish] La historia como hazaña de la libertad – (The Philosophy of History and the Duty of Freedom)];

M.A. Dinnik, History of Philosophy I;

- Engels, Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy, Dialectics of Nature;

- Gilas, The New Class;

- Lenin, The Development of Capitalism in Russia, Materialism and Empirio-Criticism, Certain Features of the Historical Development of Marxism, Philosophical Notebooks;

Liu Shaoqi, Internationalism and Nationalism;

- Lukács, The Young Hegel and the Problems of Capitalist Society;

Mao Zedong, On Practice;

- Marx, Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right;

- Mondolfo, Historical Materialism in F. Engels;

- Trotsky, The Permanent Revolution, History of the Russian Revolution I and II;

- Stalin, Marxism and the National and Colonial Question, The National Question and Leninism, Problems of Leninism;

- Wright Mills, The Marxists.

A last name on the list – the only one for the month of September 1967 – was first roughly identified as “F.O. Nietzsche”, bringing a sparkle to the eyes of those who were already hoping to write an essay on Che’s potential “supermanliness”. However, Carlos Soria later better deciphered the name and established that it was the great military expert Ferdinand Otto Miksche (1904-1992) and his work Secret Forces [cf. CQGF. No. 8/2010, p. 273].

For many years we did not know how to interpret that list of books, so wide but also so apparently disordered as to make one suspect that instead it must have had its own order, albeit very hidden. How else could it be explained that it had been jotted down in a diary that functioned as a military diary and in a situation that was certainly not conducive to study.

Moreover, the quantity of over a hundred books (some in large volumes) would have been too excessive for imagining that Che could have taken them with him during guerrilla movements.

And if he had left those books in hiding places built by him in camps prepared in the early months – and thus confiscated by the army after their discovery – they would surely have re-emerged in the “clandestine” market of Guevarian objects run for years by some of the officers who had taken part in counter-guerrilla operations: the military, in fact, privately sold everything that belonged to Che, and his supposed “travelling library” would certainly have had very high starting bids.

All that remained was to think of a wish list formulated by a Marxist scholar such as Guevara, who had a wide range of interests and had already proved to be a great devourer of books throughout his life. Or, alternatively, to think that it was a precise reading plan, in which the “Marxological” sector was of particular importance.

This second hypothesis turned out to be correct, but we were only able to confirm it some time later, with the emergence of a new document which had remained unpublished for a long time despite the importance it would have had “in the heat of the moment” for a precise definition of the most authentic Guevarian theoretical dimension.

The wave of nonsense written after his death in books and articles on Che’s “Marxism-Leninism” and on his presumed orthodoxy could have been avoided thanks to the letter I am about to examine and which provides the explanatory key to the “Bolivian” reading scheme mentioned here.

* Roberto Massari, an Italian publisher, graduated in Philosophy in Rome, Sociology in Trento and Piano Studies at the Conservatory of Perugia. He has been President of the Che Guevara International Foundation since 1998 and is moderator of the Utopia Rossa (Red Utopia) blog. Translated from Italian by Phil Harris. [IDN-InDepthNews – 16 August 2018]

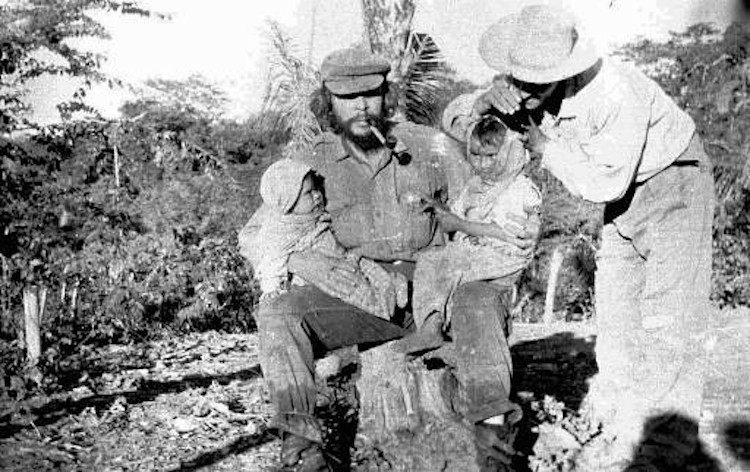

Photo: Guevara in rural Bolivia, shortly before his death (1967). Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

IDN is flagship agency of the International Press Syndicate.

facebook.com/IDN.GoingDeeper – twitter.com/InDepthNews