By Jonathan Power*

LUND, Sweden | 5 January 2026 (IDN) —What drives people to extremes? Why do the people behind Al-Qaeda or the Islamic State (IS) get so charged up and angry?

To understand this dynamic, it is helpful to return to 16th-century Europe and the furious debates over the divine right of kings. Monarchs increasingly placed themselves beyond the reach of their subjects. William of Orange, leader of the Netherlands, claimed he had “received his power from God and God alone.”

Similarly, Philip II of Spain sought to enforce Catholic orthodoxy after Spain conquered Holland, brutally repressing Protestant “heresy” through the Spanish Inquisition.

The result was revolt. In 1581, the Dutch formally withdrew their allegiance from Philip II, rejecting the idea that rulers answered only to God. Accountability to the people, not divine authority, became the new principle.

England followed a similar but bloodier path. Under Elizabeth I and James I, belief in divine monarchy endured—until the reign of Charles I. Civil war, parliamentary rebellion, and the king’s execution in 1649 shattered the doctrine. The poet John Milton wrote, “All men naturally were born free,” while John Locke later argued that government exists to protect citizens through accountable, collective authority.

Faith, Corruption, and Religious Extremism

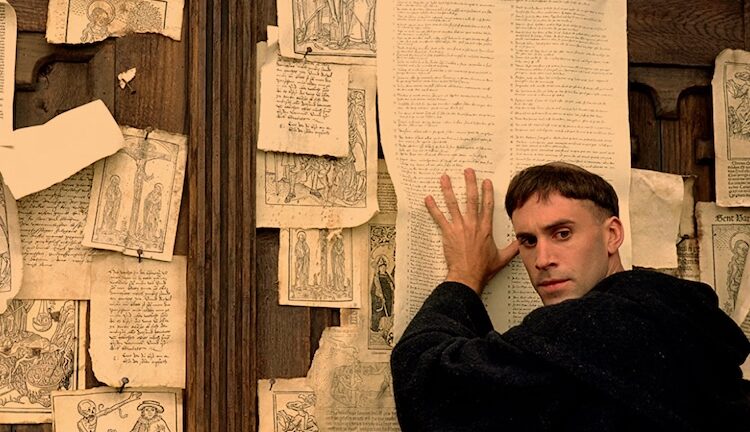

The assault on divine monarchy ran parallel to a revolt against corruption in the Church. In 1517, Martin Luther challenged papal authority, insisting that faith in God—not obedience to the pope or king—was the path to salvation. His challenge helped ignite Protestant extremism, particularly in Holland, where iconoclasts in the 1560s stormed Catholic churches, smashing statues and destroying symbols of accumulated wealth.

Their rage was moral as much as political. Today, we would label them violent religious extremists.

Sarah Chayes draws this historical parallel sharply in her book Thieves of State. She argues that the language and motivations of Al-Qaeda and IS closely resemble those of early Protestant insurgents railing against corruption and unaccountable power. Both movements frame violence as moral purification.

Like their 16th-century counterparts, Al-Qaeda and IS are intensely puritanical—hostile to alcohol, music, romance, and celebration, and ruthless toward non-conformists. Their destruction of Sufi shrines in Timbuktu mirrors earlier Protestant attacks on Catholic symbols.

Extremism, Corruption, and the Modern World

Today’s Islamic militants rage against kleptocratic kings and dictators across the Middle East and Africa—rulers who behave as though they possess a divine right to govern—and against Western governments that prop them up. In Europe, monarchy and the Church have gradually shed many anachronistic claims (even if corruption and elite dominance persist, as Pope Francis himself frequently acknowledges).

The argument follows that Al-Qaeda, IS, and their successors will fade only when authoritarianism, corruption, and extreme inequality are confronted—when rulers stop trampling the needy and claiming absolute authority. That critique extends not only to traditional strongmen but also to modern leaders who concentrate power and erode democratic accountability, including Donald Trump, Volodymyr Zelensky, and Vladimir Putin.

Until political systems undergo genuine, root-and-branch democratic reform—and until corruption is curbed rather than protected—history suggests that moral fury will continue to find violent, extremist expression.

*Jonathan Power has been an international foreign affairs columnist for over 40 years and a columnist and commentator for the International Herald Tribune (now The New York Times) for 17 years. [IDN-InDepthNews]

Copyright: Jonathan Power