By Jeffrey Moyo

HARARE (ACP-IDN) – Enrolment in primary education in developing countries has reached 91 per cent but 57 million children remain out of school. More than half of children that have not enrolled in school live in 48 countries from Sub-Saharan Africa, which are members of the 79 African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States (ACP). An estimated 50 per cent of out-of-school children of primary school age live in conflict-affected areas.

Sub Saharan Africa is home to 17 of the 33 countries and territories the International Finance Corporation (IFC) of the World Bank Group classifies as ‘fragile or conflict affected’. The IFC Conflict Affected States in Africa Initiative (CASA) is active in Burundi, the Central African Republic, Cote d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Sierra Leone, and South Sudan.

Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG4) as one of the 17 goals endorsed by the United Nations in September 2015, accentuates the need to “ensure inclusive and quality education for all and promote lifelong learning”.

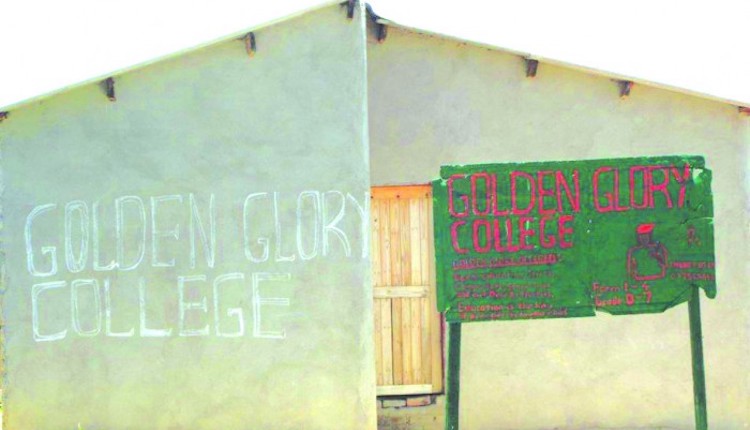

With an eye on achieving SDG4, many African countries’ towns and cities have are being swamped with shabby backyard schools especially around high density areas and illegal settlements dotted around the cities.

The lack of adequate educational facilities in emerging residential areas in some towns and cities on the continent has also led to entrepreneurs capitalising on the crisis, setting up substandard school facilities to accommodate the continent’s less privileged, which educationists have derided.

One such facility is at the heart of Dzivarasekwa high density suburb in Harare, the Zimbabwean capital: two corrugated structures lying side by side with two classroom blocks built from un-plastered home-made bricks. Since it is not a proper school, it is not recommended by the local authorities.

But for backyard school proprietors like Nicholas Chigumira in Harare, giving education to the pupils with no access to proper schools has become a brisk business. “Parents have no choice because getting places for their children at schools in other residential areas has become hard over the years and over the years, for business people like me, it has become a big business for us to provide education facilities for such people,” Chigumira told IDN.

“Surely, one cannot expect to produce good results when pupils are learning in open-air. What such pupils would focus on more are the hazards they are exposed to than the education they have to receive,” Obert Mugoni, a teacher at a farm school in Goromonzi, a district in Zimbabwe’s Mashonaland East Province, told IDN.

But parents sending their children to these makeshift schools blame poverty which they say has impelled them to enrol their children at makeshift schools. “These schools charge very low school fees and this helps us because we have no reliable sources of income,” Denford Chitembwe, a parent with two children learning at a makeshift school in Harare’s Caledonia informal settlement, told IDN.

To relieve the situation, the European Development Fund (EDF) – the EU’s main instrument for providing development aid to ACP countries and to overseas countries and territories (OCTs) – is in its 2014-2020 programme supporting Education in 40 partner countries, at least half of these in fragility contexts. EU funding for education in developing countries is expected to total 4.7 billion Euros.

For instance, in 2014, the EDF supported South Africa’s Department of Basic Education to provide school buildings, furniture and fittings, water, sanitation and electricity to under-resourced schools. Due to this support, South Africa’s crisis in education infrastructure is now history.

Even some of the teachers there are all smiles. “We are so excited to have well-built brand new classrooms. Now when it rains, the roofs here no longer make noise for the learning children,” Nomphumelelo Zwane, a school teacher based in South Africa’s Eastern Cape Province, told IDN in a telephone interview.

In Uganda, the smiles could be even wider. In the East African nation in 2017, the EDF helped construct 28 blocks of 84 classrooms, 28 blocks of 140 stances of inclusive gender-segregated pit latrines and 40 teachers’ houses in the country’s Bidibidi and Omugo refugee settlements to ensure a safe and inspiring learning environment for South Sudanese refugees domiciled there.

In Southern Africa in May 2015, Malawi and the EU signed the national indicative programme up to 2020 to the tune of 560 million Euros. Its focus in the education sector is on (i) improving the facilities and strengthening secondary schools and vocational and technical education bodies and training institutions; (ii) improving the quality and relevance of secondary education and vocational training, including through the rehabilitation of school infrastructures and (iii) promoting equitable and gender-based access to secondary education and vocational training.

Further up Tanzania is a significant beneficiary of the EDF, receiving 626 million Euros in the 2014-2020 cycle. The East African nation’s priority sectors for poverty reduction such as education, have been receiving financial backing in millions of Euros resulting in the country’s primary school enrolment rate doubling over the past decade, with 90 percent of the children now attending primary school.

In Zambia, thanks due to the EDF, 74 Community Schools are operating in Chipata making the right to education a reality. “The whole process has really been very consultative during the implementation of this project, living a mark of good relationship with the community schools and the DEBS office. The project increased learning space, improve water and sanitation and implemented sensitization activities for students that will go a long way in helping a girl child to go back to school and actually stay in school,” said Herbert Mwiinga, Chipita District Education Board Secretary (DEBS).

However, not all schools in Zambia have gained from the EDF, while other school infrastructures are now aged and dilapidated. “During the commencement of every rainy season here, some school buildings become uninhabitable as grass thatched roofs have worn out and therefore leak,” a top education official from Zambia’s Ministry of Education, told IDN in a telephone interview on condition of anonymity. [IDN-InDepthNews – 12 May 2018]

Photo credit: The Financial Gazette, Zimbabwe

This report is part of a joint project of the Secretariat of the ACP Group of States and IDN, flagship agency of the International Press Syndicate.

facebook.com/IDN.GoingDeeper – twitter.com/InDepthNews