By Salah Uddin Shoaib Choudhury

DHAKA | 2 January 2024 (IDN) — For many decades, Muhammad Yunus succeeded in remaining in the attention of international media and global celebrities and leaders by continuing self-promotion as the ‘savior of the poor’, ‘father of microcredit’ etc.

Interestingly, many leaders in the West, including former US First Lady Hillary Clinton, remain a great admirer of Muhammad Yunus. Not just because the Clinton family considers him an angelic individual but because Yunus has been one of the biggest donors of the Clinton Foundation.

While Yunus succeeded in duping almost the entire world into an intriguing web of lies and falsehood, in Bangladesh, millions of poor people are visibly bleeding, being trapped in the debt trap of Grameen Bank as well as multiple microfinance ventures of this monstrous individual, who has been robbing-off poor with an excessive amount of interest on the amount Yunus lends.

While Yunus succeeded in duping almost the entire world into an intriguing web of lies and falsehood, in Bangladesh, millions of poor people are visibly bleeding, being trapped in the debt trap of Grameen Bank as well as multiple microfinance ventures of this monstrous individual, who has been robbing-off poor with an excessive amount of interest on the amount Yunus lends.

But none of the exposures of him being a blood-sucking lender and cause of suffering, starvation, and even death of a massive number of poor in Bangladesh – the name Muhammad Yunus stands out prominently, hailed as the pioneer of microcredit and the founder of Grameen Bank. He has been given accolades after accolades and even projected as a saintly individual.

However, lately – beneath the surface, a series of controversies have marred the reputation of Yunus, his brainchild Grameen Bank, and its affiliated organization, Grameen Telecom and Grameen Kalyan.

Financial irregularities

One of the primary accusations facing Yunus and his affiliated entities revolves around financial irregularities, including tax evasion, embezzlement, and the misappropriation of funds from various affiliate organizations. The case involving Grameen Telecom, where a legal obligation to share 5 percent of profits with employees allegedly went unfulfilled, resulted in a case filed under Sections 4, 7, 8, 117, and 234 of the Labor Act in Bangladesh. This highlights the serious legal implications and underscores the need for a comprehensive investigation.

The involvement of 106 Nobel Laureates urging Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to halt legal proceedings against Yunus adds a layer of complexity to the situation. While the laureates may argue that Yunus is being persecuted, critics maintain that this international support ignores the constitutional limits and may inadvertently undermine the rule of law.

Bangladesh government committee’s findings in 2011, revealing rule breaches and fund misuse, further stress the importance of an unbiased examination of the allegations.

Another significant point of contention arises from the alleged manipulation of Grameen Bank’s ownership structure. Initially, members owned 60 percent of the shares, with the government holding the remaining 40 percent. However, investigations indicate that a 1986 amendment shifted the balance, giving the members 75 percent of the shares and only 25 percent to the government. This apparent violation of Section 7 of the Grameen Ordinance raises questions about the transparency and legality of such changes.

Legal experts in Bangladesh argue that the increase in paid-up capital by Grameen Bank lacks proper authorization. According to them, the power to increase paid-up capital rests solely with the government, and any unilateral action by the bank may constitute a breach of the law. The absence of documented evidence showcasing government authorization for the increase raises concerns about the adherence to legal procedures within Grameen Bank.

The process surrounding the appointment of Muhammad Yunus as the Managing Director of Grameen Bank has also come under intense scrutiny. While the initial appointment by the government followed due process, subsequent amendments shifted the responsibility to the Board of Directors.

However, discrepancies in Yunus’s appointment, including exceeding the age limit set by government employment rules, cast doubt on the legitimacy of his tenure. The violation of service rules, particularly the alleged absence of reapproval from Bangladesh Bank, adds another layer to the controversy.

Yunus’s classification as a public servant, as defined by the Bangladesh Penal Code, adds a legal dimension to the controversies. The 2011 review committee identified several breaches of service terms, including frequent absence, unauthorized foreign travel, and the acceptance of funds without proper permissions. The alleged concealment of Yunus’s position while establishing affiliated ventures abroad further complicates the narrative.

A true story of Sufia Begum

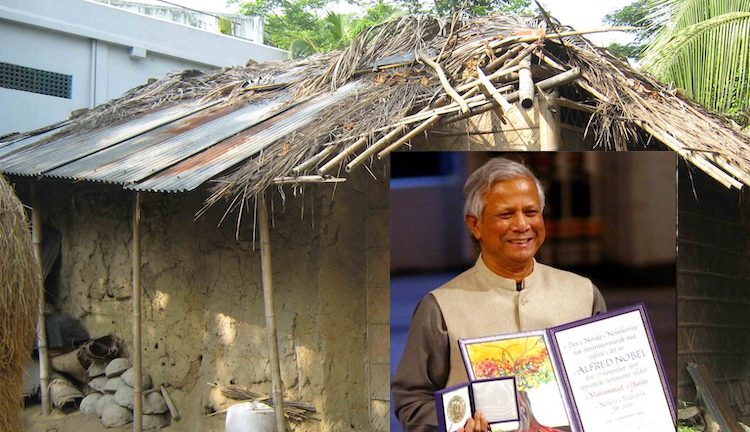

Yunus projected Jobra village and Sufia as examples of their excellent success stories to the international audience. Yunus has attained tremendous attention from the international community through such a campaign. He has gained fame worldwide as a ‘pioneer’ of microcredit, for which he got the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006.

The name of Sufia, the first loan borrower from Yunus’s Grameen Bank, has already crossed the international boundaries of many countries, as Grameen Bank proudly pronounced her name as one of the brilliant success stories of their so-called micro-credit loans. It is beyond the knowledge of many that, almost one decade back, Sufia died due to extreme poverty and lack of any minimum medical treatment.

Sufia Begum was the first borrower of a microcredit loan from Muhammad Yunus among the villagers of Jobra in Bangladesh. Sufia died on 16 January 1997, leaving two daughters—Nurunnahar and Fazilatunnhar. Sufia died in utter poverty.

Sufia Begum’s husband had died long before her death during the childhood of their daughters. He was a job-holder in a tiny local business farm. After his death, Sufia became the only earning member of her family. She used to deal with vegetables. Sufia somehow managed to arrange the marriage of her daughters after her husband had died. Even after marriage, both the daughters were living beside Sufia’s homestead. They separated from her mother’s family, though they had a reciprocal relationship regarding earning and sharing livelihood.

Sufia’s daughters have been living in the east corner of the village adjacent to a mosque. There are three separate houses, two of those are of two sons’ of Fazilatunnahar’s and the other is of younger daughter Nurunnahar’s son.

Sufia Begum took a loan from Grameen Bank more than 25 years ago. First, she took taka 60. At that time, she had to deposit one taka per day. Having paid the loan back, Sufia took taka 500 and paid it back. Even after that, she took another 500 takas and paid in irregular installments. But she never got back her deposit from Grameen Bank. At that time, dealing with vegetables and food grains was insufficient to sustain her livelihood. So, she was somewhat dependent upon the incomes of her daughters’ family. At that period, due to the economic hardship and the pressure of a loan from Muhammad Yunus’ Grameen Bank, Sufia’s elder daughter lost her mental balance.

Both daughters live in the same place besides Sufia’s homestead with their children and grandchildren. Both of them and their children are so poor that they could not take any loan from either Grameen Bank or any other NGO.

Sufia’s elder daughter, Fazilatunnahar, has two sons. Fazilatunnahar’s husband left her and got married again. Both of her sons are rickshaw pullers and are married. They have lived with their wives, children, and mother in two tiny straw-roofed huts.

A few months before the younger one was unemployed, a wealthy neighbor gave him a rickshaw on the condition that he would pay the price back gradually. Fazilatunnahar has yet to get her mental balance back. She gets furious when she confronts outsiders from the village and starts deploring the harms of the loan. She even scolds the journalists and television crews who frequently visit her house.

The younger daughter of Sufia Begum—Nurunnahar—has two sons and one daughter. Her husband also left her for a long time. All of her children but one is married, though the daughter’s husband has left her with a child. All of them have been living as one family. Nurunnahar’s elder son is also a rickshaw puller and the only earning member of the family. All of them have been living in a small hut. Though it needs to be repaired, their family cannot afford it due to poverty. During the rainy season, water falls from the roof, making it difficult for them to dwell in the hut.

Nurunnahar told Danish investigative journalist Tom Heinemann that after receiving the Nobel Prize when Yunus visited Jobra village, Grameen Bank had forced the locals to collect money to buy Yunus flower bouquets. At that time, Muhammad Yunus, in the presence of the villagers, had promised to provide financial assistance to Sufia Begum’s family so they could build a new house. But this was just a false promise. Instead of helping Sufia Begum’s family in repairing their broken hut, a propaganda team of the shrewd Muhammad Yunus sent journalists from France, China, Germany, and a few more countries to Jobra village and film an adjacent building and claim it to be owned by Sufia Begum. In reality—the building belongs to an expatriate named Jabel Hussain, who lives in Dubai.

A tangled web

The controversies surrounding Muhammad Yunus, Grameen Bank, and Grameen Telecom present a tangled web of financial, legal, and ethical issues. While media and international support may cast Yunus as a victim, the evidence suggests a more nuanced reality. The intertwining of financial irregularities, ownership structure manipulation, and appointment controversies demands a thorough and impartial investigation. As these allegations continue to capture global attention, accountability and adherence to legal processes remain paramount to ensure justice prevails over influential affiliations and international support.

According to media reports, a court in Bangladesh has sentenced Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus to six months in jail for violating the country’s labor laws. Following the verdict, Yunus told reporters, “As my lawyers have convincingly argued in court, this verdict against me is contrary to all legal precedent and logic. I call for the Bangladeshi people to speak in one voice against injustice and in favor of democracy and human rights for every one of our citizens”.

Here again, Yunus has resorted to his old habit of falsehood, and most possibly onwards, he will take advantage of coverage in the international media by misleading them through his PR team. In this case, if journalists are to follow the ethics of this noble profession, they need first to investigate Yunus’s dark actions. And in that case, instead of defending this man, they will accuse him of deceiving millions of poor women in Bangladesh for decades. [IDN-InDepthNews]

*Salah Uddin Shoaib Choudhury is an internationally acclaimed multi-award-winning anti-militancy journalist, writer, research scholar, and editor of Blitz, a newspaper published in Bangladesh since 2003. He regularly writes for local and international newspapers. Follow him on X@Salah_Shoaib [IDN-InDepthNews]

Photo: The broken hut of Sofia Begum, who died of poverty, though the 2006 Nobel Peace laureate Muhammad Yunus claimed his microfinance had helped her become self-reliant and wealthy. Photo credit: Blitz Weekly

IDN is the flagship agency of the Non-profit International Press Syndicate.