By Jan Servaes*

BRUSSELS, 28 March 2023 (IDN) — I first watched Mike Chinoy during the so-called Tiananmen ‘revolt‘ in 1989 when he and ‘anchor’ Bernard Shaw reported live from the roof terrace of the Peking Hotel for the relatively new and ambitious American TV channel CNN of what was happening on Tiananmen Square.

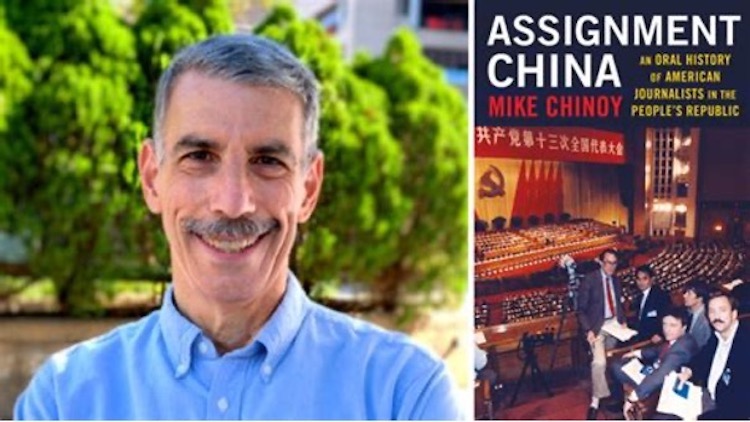

A graduate of Yale and Columbia University, Chinoy began his career as a radio and television reporter for CBS News and NBC News. Fascinated by Asia, he ended up in China as a foreign correspondent in the 1980s and became CNN’s first bureau chief in Beijing from 1987 to 1995.

He has won several awards for his coverage of China. He currently lives in Taiwan and is a non-resident senior fellow at the US-China Institute at the University of Southern California (USC).

Assignment China: the TV series

From 2008 Chinoy produced a 12-part documentary series ‘Assignment China’ for USC, together with supervisor Clayton Dube, in which China is viewed through Western, mainly American, glasses.

Viewers new to the China story are given a vivid introduction to 70 years of political, social and economic change through the eyes of (mostly American) journalists who covered it. As China followed a winding path from war to Maoist revolution to its current state of prosperity and ‘digital authoritarianism,’ US correspondents faced ever-changing challenges.

Yet wave after wave of reporters understood the importance of the story and developed a fascination and even ‘obsession’ with China: “A central theme that emerged in virtually all interviews was the curiosity, passion, courage and cunning that journalists have to show to get their story”, Chinoy says on page 7 of his book.

The following themes are successively discussed in the video series:

The Chinese Civil War

With Japan’s defeat, the Kuomintang and communists soon returned to their struggle for control of China. This segment focuses on the work of journalists covering the civil war that ended when Mao Zedong proclaimed the establishment of the People’s Republic atop Tiananmen.

China watching

Largely excluded from China, American journalists in the 1950s and 1960s had to try to cover the tumultuous changes in the world’s largest nation from the periphery, mainly from Hong Kong. This segment explores how they did this and how some US news organizations only occasionally received reports from China.

The week that changed the world

US President Richard Nixon’s 1972 trip ended two decades of Cold War hostility. America’s most famous journalists were the first to go with the president, though most had no idea what they might find. “It was like going to the moon”. This segment shows how both governments try to control reporting and how journalists struggled to report ‘objectively’ on the historic visit.

The end of an era

While the Nixon trip sparked discussions between the US and China, China was only slightly more open to Americans than it had been. American journalists were only allowed to visit for short periods. This segment discusses coverage of the period through 1976, when the deaths of Zhou Enlai and Mao Zedong sparked political clashes and the Tangshan earthquake claimed a quarter of a million lives.

Opening up

With the restoration of formal diplomatic relations on January 1, 1979, American news organizations were able to send journalists into China. Interest in China was enormous, as evidenced by the coverage of Deng Xiaoping’s visit and the economic reforms he initiated. The press also covered the new family planning policy and the outbreaks of dissension within the CCP.

The eighties

Deng Xiaoping and the reformers he installed in top positions dramatically loosened economic and social control in the mid-1980s. Journalists documented how Chinese embraced this opening and how some Chinese tested the party state’s tolerance of dissent. Some journalists, protesters and even leaders clashed with party hardliners and were punished for crossing vague boundaries.

Tiananmen Square

In 1989, students marched in cities across China, but it was the demonstrations in China’s symbolic centre, Tiananmen Square, that caught the attention of people around the world. Because of the first Sino-Soviet summit in thirty years, there were more journalists in Beijing than usual and the Chinese authorities initially allowed easier satellite access. This segment shows how journalists attempted to understand what was happening and to help their audience understand the issues and forces at play, which ultimately included the violent suppression of the protests.

A tale of two Chinas

The 1989 crackdown ushered in a period of political repression in China, but as the 1990s progressed, the economy grew, migration became more common, and individual Chinese had more control over their own lives. While reporters faced constant surveillance and harassment, conditions improved towards the end of the decade to the point that some saw it as the beginning of a golden age of reporting in China.

The new millennium

The 2000s were a heady time in China. In 2000, the country won the right to host the Olympic Games, and in 2001 it joined the World Trade Organization and its economic growth accelerated. But soon after, suppressing information about disease outbreaks not only hindered reporters, it threatened public safety. There was increasing tension about how some gained and lost economically and how the environment was damaged. At the same time, social liberalization and technological change enabled reporters to explore new regions and issues.

Tremours

China entered 2008 full of expectations. Beijing would be the centre of world attention with the Summer Olympics. But in March, the repression sparked riots in Tibet and the Olympic torch relay sparked protests outside China. Then, in May, an earthquake killed 70,000 people and left millions homeless. Even more than usual, the party state was concerned about image management at home and abroad. While the games were a huge success in public diplomacy, reporters were irked by the government’s failure to ease travel and other restrictions as promised.

Contradictions

China’s foreign press corps hoped that once the Olympics were over, restrictions on their movement and other activities would be eased. They weren’t. At the same time, the Chinese state invested heavily in expanding its own international media, trying to push aside foreign media images of China and its policies. While the West stumbled economically, China appeared to have weathered the storm and pursued a more assertive foreign policy. China’s economic rise had led to a dramatic expansion of the US press corps but covering China’s conflicting trends was no less challenging.

Follow the money

China’s economic rise had been the dominant thread in the country’s story for two decades. It had long been grumbled that those with connections would benefit disproportionately from this advance. In 2012, two US news organizations documented the immense but hidden fortunes amassed by the relatives of President Xi Jinping and Wen Jiabao, the outgoing prime minister. After other journalists spread stories of scandals, the Chinese state denied visas to these organizations and attempted to intimidate others.

I used these documentaries extensively at the City University of Hong Kong during my ‘China in the Eyes of Western Media’ course co-taught with Yuhong Li, a former CCTV journalist, from 2013 to 2015. Mike Chinoy, then living in Hong Kong, has been a regular guest speaker. The video about Tiananmen in particular was an eye-opener for most ‘mainland students’.

*Jan Servaes is editor of the 2020 Handbook on Communication for Development and Social Change (https://link.springer.com/referencework/10.1007/978-981-10-7035-8) and co-editor of SDG18 Communication for All, Volumes 1 & 2, 2023 (https://link.springer.com/book/9783031191411) [IDN-InDepthNews]

Image credit: library.ucsd.edu

IDN is the flagship agency of the Non-profit International Press Syndicate.

Visit us on Facebook and Twitter.

We believe in the free flow of information. Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International, except for articles that are republished with permission.