By Jan Servaes*

BRUSSELS (IDN) — On December 22, 2022, Thailand hosted a meeting in Bangkok to discuss the Myanmar crisis. This meeting was attended by the foreign ministers of the Myanmar junta, Laos and Cambodia, as well as the deputy foreign minister of Vietnam. Significantly, Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia and Singapore did not attend.

It could therefore not be called an official ASEAN summit. After all, there is disagreement among the 10-member group about whether or not to cooperate with the junta.

The meeting came a day after the UN Security Council passed its first resolution on Myanmar in 74 years. China, Russia and India abstained. The other 12 members voted in favour. The resolution expresses “deep concern” over the continued state of emergency imposed by the military when it seized power and its “serious impact” on the people of Myanmar.

The UN Security Council urges “concrete and immediate actions” to implement a peace plan agreed by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and calls for “maintaining democratic institutions and processes and for a constructive encounter between Thai and Burmese to pursue dialogue and reconciliation in accordance with the will and interests of the people”.

Myanmar’s junta did not return calls for comments.

This was not the only recent high-level encounter between Thai and Burmese military leaders. On January 20, 2023, a meeting took place in Rakhine State, western Myanmar, between the top leaders of the Myanmar and Thai armed forces, in particular the Chief of the Royal Thai Armed Forces, General Chalermphon Srisawasdi, and junta leader Min Aung Hlaing.

According to The New Light of Myanmar, the junta’s propaganda newspaper, the aim was to “further strengthen mutual trust, mutual understanding and friendly ties between the two forces”.

While this high-level meeting was taking place, the Myanmar Air Force launched airstrikes against a village in the Sagaing region, killing at least seven villagers and injuring more than 30.

On several similar occasions, stray grenades have landed on Thai territory as the Myanmar military launched airstrikes in neighboring states of Karen and Karenni.

Corruption as glue

Rumors have been circulating for some time about the close cooperation of the Thai army with the junta in Myanmar. Historically, relations were not always good. Often reference is made to a variety of factors, including border disputes and ethnic conflicts.

Both countries are also known to support separatist groups within each other’s borders, which has led to military tensions.

But in recent years, especially since the Thai military coup of 2014, relations between the two countries in general, but especially in terms of military cooperation, have improved significantly. A Thai expert group concluded more than a year ago that current Thai foreign policy has fallen to its “lowest point” in living memory.

A common characteristic between the two countries appears to be the widespread corruption within the Thai and Burmese armies. In Thailand, there have been numerous reports of corruption within the military, including embezzlement, bribery and abuse of power. This has led, according to Transparency International, to a loss of public confidence in the military.

In Myanmar, the military (or Tadmadaw) has long been accused of corruption and human rights violations. The army has grown into a military-industrial complex that controls large parts of the country. In addition, the Tatmadaw has been accused of using its power to enrich itself and its members through illegal means such as drug trafficking, extortion and illegal logging.

It recently became known that Myanmar has been growing more opium since the 2021 coup. This has reversed a six-year decline between 2014 and 2020, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), placing it second after Afghanistan on the list of opium-producing countries.

Distribution and trade is largely arranged through Thailand. The regional heroin trade is estimated to be worth as much as $10 billion, while Myanmar’s total opium economy is worth $2 billion.

Recent discoveries and seizures by Thai police of assets belonging to senior general Min Aung Hlaing’s adult son and daughter suggest that military figures are using Thailand as a financial safe haven. Assets belonging to the children were found by Thai police on September 27, 2022, during a raid on the Bangkok apartment of a Myanmar tycoon, Tun Min Latt, who is currently in custody for drug trafficking and money laundering charges.

A Reuters report (published in the Bangkok Post), citing an official report and two people with knowledge of the matter. The discovery of the documents indicated close ties between Tun Min Latt and the family of the head of the Myanmar junta.

Ties forged in ‘brotherhood’

A spokesperson for the Justice for Myanmar research group said the discovery also shows “senior military relatives of Myanmar have access to Thai banks and more generally to Thailand as a destination to hide their illicit profits from the systemic corruption of the military. This despite sanctions and other measures that try to limit the junta’s access to the international financial system.

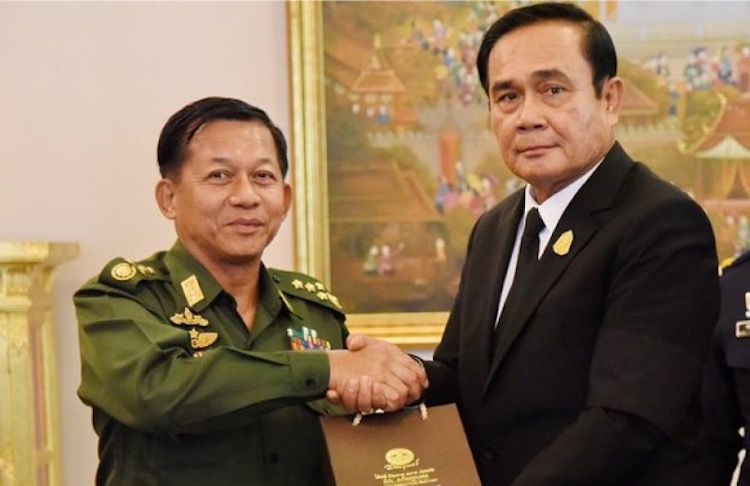

Unsurprisingly, Min Aung Hlaing’s family sees Thailand as a safe haven for their stolen wealth. Min Aung Hlaing has a close relationship with Prayut Chan-o-cha, who became prime minister after leading a military coup in 2014. After the attempted coup by the Myanmar army, Prayut and Min Aung Hlaing maintained contact through loopholes and the special envoy from Thailand to Myanmar. Prayut has spoken out against sanctions. Thailand finances the junta’s terror campaign by importing natural gas.”

Justice for Myanmar and the ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR) are therefore urging the Thai government to end its close relations with the Myanmar junta, which continues to commit various atrocities against its own people. The APHR is calling on Thai authorities to provide assistance to refugees and asylum seekers fleeing persecution and military attacks from the neighboring country.

“By partnering with the junta, the Thai military and government become facilitators of the crimes against humanity it commits on a daily basis. No geopolitical interest can justify that. The junta has also shown a complete disrespect for ASEAN, of which Thailand is also a member, by ignoring the five-point consensus it signed three months after the coup.

No ASEAN member state should have ‘friendly ties’ with an army that has turned Myanmar into a center of instability that threatens the entire region,” stated Charles Santiago, co-chairman of the ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR).

As the APHR has repeatedly argued, junta leader Min Aung Hlaing has shown no willingness to comply with the terms of the five-point consensus from the outset. The report of the International Parliamentary Inquiry into the Global Response to the Myanmar Crisis (IPI), urged ASEAN to abandon the Five Point Consensus in its current form as it has clearly failed.

“As we demanded in our IPI report, ASEAN should involve Myanmar’s National Unity Government (NUG) as the country’s legitimate authority, and renegotiate a new consensus with it and aligned ethnic organizations. ASEAN decided early on not to invite junta representatives to high-level meetings, and countries such as Malaysia and its current chairman, Indonesia, have shown a willingness to involve the NUG. By meeting Ming Aung Hlaing, Thailand undermines those efforts and furthers division within the regional group,” said Santiago.

Displaced people on both sides of the border

Thailand and Myanmar share a border of more than 1,500 miles, and the junta’s attacks have displaced hundreds of thousands. Yet Thailand refuses to take in refugees fleeing attacks by the Myanmar army on the other side of the border.

Refugees crossing the border are often pushed back after a few days or even a few hours, as human rights groups have often denounced over the past two years. Asylum seekers from neighboring countries do not fare much better in Thailand. They have no legal protection and are in constant fear of deportation.

For example, in June and July 2022, the village of Ukayit Hta in Kayin State was destroyed by airstrikes by the Burmese army. The attacks made international news when a Burmese fighter jet violated Thai airspace, but seven months later those who fled Ukayit Hta have been forgotten and are still sheltering in makeshift camps along the border of the Thaung Yin River.

The Border Consortium is the main provider of food, shelter and other forms of support to approximately 90,000 Myanmar refugees living in nine camps in western Thailand. It also supports rehabilitation and community-led development in conflict-affected areas of southeastern Burma.

The map below shows the population figures in the refugee camps, updated to December 2022 and verified by the UNHCR. .Thailand continues to host 90,617 Myanmar refugees in its nine managed temporary shelters on the Thailand-Myanmar border, in addition to approximately 5,000 urban refugees and asylum seekers from more than 40 countries, and some 480,000 persons are registered as stateless. For many aid organizations and NGOs, it remains a difficult dilemma to help people in need without giving legitimacy to the junta.

“Thailand has a history of welcoming refugees from Laos, Cambodia or Vietnam since the 20th century wars in Indochina. The government should open its borders to the refugees fleeing war in Myanmar’s ethnic states along its borders, and provide legal protection to those seeking political asylum, including defectors from the Myanmar military. It should also facilitate cross-border aid by local civil society organizations and international NGOs.

Again, on these issues, the main interlocutors the Thai government should engage with in Myanmar are the NUG, aligned ethnic organizations and vibrant civil society. Not a criminal army utterly incapable of solving the crisis it has created,” Santiago concluded on behalf of the APHR.

‘Junta elections’ in 2023?

Two years after Myanmar’s military staged a coup against the democratically elected government, the country has sunk deeper than ever into crisis and an overall human rights decline, UN human rights chief Volker Türk said on Jan. 27.

“By almost every available measurement, and in every field of human rights – economic, social and cultural, as well as civil and political – Myanmar has regressed sharply,” he concluded in a press release.

Still, a few months after the coup, the Burmese junta announced plans to hold new general elections in August 2023. The long run-up to the elections would give the junta time to consolidate power in Myanmar. It is now feared that the election exercise, designed to stabilize the political situation, is more likely to fuel the country’s nationwide conflict.

Therefore, junta spokesman Major General Zaw Min Tun told the Voice of America (VOA) that there is still “uncertainty about whether a general election will be held this year”.

The Civil Disobedience Movement, the NUG and other opposition groups are already calling for a ‘silent boycott’ of elections. And also Derek Chollet, adviser to the US State Department and the Biden government’s representative for Myanmar, said in an interview with VOA that there is “no chance” that Myanmar’s proposed elections will be free and fair. “You cannot have free and fair elections if you imprison every significant opposition, if you commit atrocities, and if you shut down a free press.”

Logistically, he said it is “unclear” how the junta could hold elections, as “they don’t currently control up to 50% of the territory” – seemingly a reference to resistance claims of the military’s significantly reduced territorial control. Chollet may have reached this conclusion because the US is, in his own words, “very involved” with the Government of National Unity (NUG) and “some of the ethnic groups”.

Let’s wait and see how this will turn out in Thailand and Myanmar, but also for ASEAN and geopolitics. Because as Evan A. Laksmana, a senior research fellow at the Center on Asia and Globalization at the National University of Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy predicted in Foreign Policy back in 2021: “The future of ASEAN will be decided in Burma”.

*Jan Servaes was UNESCO-Chair in Communication for Sustainable Social Change at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He taught ‘international communication’ in Australia, Belgium, China, Hong Kong, the US, Netherlands and Thailand, in addition to short-term projects at about 120 universities in 55 countries. He is editor of the 2020 Handbook on Communication for Development and Social Change. https://link.springer.com/referencework/10.1007/978-981-10-7035-8 [IDN-InDepthNews – 31 January 2023]

Image: Myanmar military chief Snr Gen Min Aung Hlaing (left), exchanged gifts with Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha on a visit to Government House in 2018. (Photo courtesy Thai Government House and Bangkok Post)

IDN is the flagship agency of the Non-profit International Press Syndicate.

Visit us on Facebook and Twitter.

We believe in the free flow of information. Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International, except for articles that are republished with permission.