Viewpoint by John Newsinger*

This is the third of a six-part article originally published in International Socialism under the title The Christian right, the Republican Party and Donald Trump. Click here for part two of the series. Any views or opinions expressed are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of IDN-InDepth News.

LONDON (IDN) – Graham was, according to one of his biographers, by this time, “something like an extra officer in Nixon’s cabinet, the administration’s own Pastor-without- Portfolio”. Or as the left-wing journalist I. F. Stone put it, he was Nixon’s “smoother Rasputin, dishing out saccharine religiosity”.

He was to support Nixon when he recognised Communist China, something that outraged many evangelicals and stuck by him even as Watergate began to engulf his administration. On occasions he even indulged the president’s antisemitism.

He agreed with Nixon that the Jewish liberals’ “stranglehold” over the media “has got to be broken or the country’s going to go down the drain”. They were the ones “putting out the pornographic stuff”. He went on to tell Nixon how the Jews “swarm around me, are friendly to me, because they know I am friendly to Israel and so forth. They don’t know how I really feel about what they’re doing to this country”.

The emergence of the Christian right

In the 1940s, the 1950s and into the 1960s, evangelical Christians had been broadly content with the way America was going and content to be part of the anti-communist crusade. An evangelical middle class had been created by the post-war boom across the South and the Midwest, embracing the “prosperity gospel”, living in a closed Christian sub-culture, and only really exercised by the Catholic threat, by the Jews and by often bitter doctrinal disagreements in their own ranks.

This all began to change in the 1960s. There were a number of factors that fuelled the emergence of the Christian right: the anti-war movement, abortion, feminism, gay liberation and encroaching secularisation. Evangelical Christians became increasingly concerned first to contain and then to roll back all the evils that they summed up under the rubric of “secular humanism”. The “culture wars” had begun. The initial impetus, however, was provided by the civil rights movement and the assault on segregation.

The Christian right itself was to later identify the issue of abortion as the decisive factor in their decision to become politically organised and active, but this is not true. It was the desegregation of state schools which led to a massive withdrawal of white children from the state sector and to a massive expansion of private whites-only Christian schools across the South and the Midwest.

According to one account, in the 1970s, “evangelicals and fundamentalists began constructing new private schools at the rate of two a day”, so that by 1979 there were some 5,000 with “more than 1 million students”.

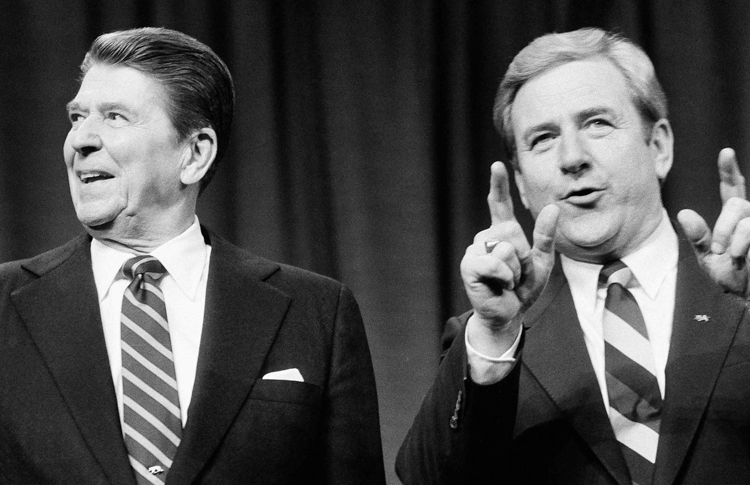

The founder of the Moral Majority, Jerry Falwell, a strong supporter of segregation at this time, was part of this movement, setting up his own all-white school to serve his own all-white church congregation in Lynchburg, Virginia. He condemned integration as something that the “true negro does not want”, claiming that he could “see the hand of Moscow in the background” and that it was all the work of the “Devil himself”. Indeed, the “Hamites were”, he insisted, “cursed to be servants of the Jews and Gentiles” and if segregation were ended “God will punish us for it”.

Falwell was himself, on one occasion, confronted by civil rights protesters when a group of white and black Christians staged a “kneel-in” at his church, demanding he integrate, and he had the police evict them. There was also a massive rise in Christian home schooling. What politicised this movement though was the 1978 decision of the Inland Revenue Service (IRS) to remove tax exemption from private schools that were segregated.

What demonstrated the full potential for a national Christian right mobilisation was the campaign against the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA): “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged… on account of sex”. This constitutional amendment had overwhelming bipartisan support. It went through Congress in 1971-2, carried by 354 to 23 votes in the House of Representatives and by 84 to 8 votes in the Senate with the full support of President Nixon. To finally pass, however, the Amendment needed to be ratified by 38 states.

The Christian right mobilised to prevent this, led by a hard-line ultra-right-wing Catholic, Phyllis Schlafly, a longstanding cold war warrior and a strong supporter of Barry Goldwater, the right-wing Republican candidate for president in 1964. On one occasion, she proclaimed the atomic bomb to be “a marvellous gift that was given to our country by a wise God”.

She launched a Stop ERA campaign in October 1972 that fought to both stop states from ratifying the ERA and to get those states that had already ratified to reverse their decision. Falwell once again threw himself into the struggle. As far as he was concerned, the ERA “strikes at the foundation of our entire social structure”, indeed it was a “satanic attack on the home”.

The campaign was successful in enough states and the remarkably anodyne ERA was never ratified. One important aspect of the Stop ERA campaign was that it saw evangelical Christians joining together with right-wing Catholics, with Schlafly even speaking at Falwell’s church. This non-sectarian bigotry was a new development.

There is no doubt that Schlafly’s campaign against the ERA excited both leading evangelicals, such as Jerry Falwell and Tim Lahaye, and leading activists on the right of the Republican Party. For Falwell’s part, he attempted to project himself nationally. In 1976, he commemorated the Bicentennial of the US by taking his Liberty Baptist College choir on an “I Love America” preaching tour of state capitols, which he later described as “the first offensive we launched to mobilise Christians across America for political action against abortion and the social trends that menaced the nation’s future”.

He repeated the tour in 1979. That same year, he published his America Can Be Saved, a manifesto of sorts, where he told readers that, “if you would like to know where I am politically, I am to the right of wherever you are. I thought Goldwater was too liberal”.

He, LaHaye and others had come to recognise the need for some sort of national evangelical political organisation and joined together with a number of hard-line Republican Party right-wingers, Paul Weyrich, Howard Phillips, Richard Viguerie and Robert Billings, to found the Moral Majority in June 1979. They were to spearhead a drive to get evangelicals registered to vote (they claimed to have registered three million people within a year and to have enlisted in their movement some seven million people within a couple of years) and then to get them out to vote Republican.

What is interesting, however, is that as far as Weyrich was concerned, what finally decided Falwell and the other evangelical leaders to launch the new movement was not any of the great moral issues they preached about, but the inconvenient activities of the Inland Revenue Service. The Moral Majority had a dual purpose: to enlist evangelical support behind the Republican Party and to ensure that the Republican Party embraced a Christian right programme.

The way to mobilise and energise evangelical support was by declaring the “culture wars”: Christian America was under attack from “secular humanism” in all its various manifestations. Indeed, it was in mortal peril – abortion, gay rights, secularism in state schools, environmentalism, pornography and feminism were all corrupting America and had to be rolled back.

The degree of cynical opportunism involved in all this is really quite staggering. Robert Billings, one of the founders of the Moral Majority and himself an ordained minister, was quite open about it: “We need an emotionally charged issue to stir up people and get them mad enough to get them up from watching TV and do something. I believe homosexuality is the issue we should use”. As Mel White, himself a gay Christian, puts it, Falwell went on to “launch a full-scale war on homosexuality and homosexuals…Falwell turned gay-bashing into an art form”.

An extract from just one of Falwell’s many fund-raising letters sent out to millions of evangelical Christians captures the tone perfectly: “Last Wednesday, I was threatened by a mob of homosexuals. This convinced me that our nation has become a modern-day Sodom and Gomorrah… Please send your $35 gift today.”

He sustained this homophobic campaign relentlessly over the years. In 1994, he bitterly condemned the Clinton administration for giving visas to athletes participating in the Gay Games in New York. These were “foreigners infected with the lethal, fatal and deadly AIDS virus”. Americans were being put at risk “just so these homosexuals can hold an Olympic Games for gays and lesbians and transvestites and bisexuals and paedophiles and sodomites”. These “deviants” were out to “recruit your children”, and so on and on.

All this helped whip up a wave of homophobia that was to even lead to the demand, in 1998, from various evangelical bodies that the King James Bible be no longer used because it had been commissioned by a homosexual and that anything “that has been commissioned by a homosexual has obviously been tainted in some way”.

The world of the Christian right

The politics of the Christian right are rooted in an evangelical subculture embracing millions of people that is unique to the United States. This subculture is unknown to many Americans, let alone to people outside the country, and when they do encounter it, its strangeness, its peculiar mix of superstition and commercialism, seems incredible.

While there is not the space here for any systematic discussion of the phenomenon, some consideration is necessary for a proper understanding of the significance of the Christian right. First, some perspective: according to the New York Times in 1982 the bestselling book in the US was Jane Fonda’s Workout Book, but this was not true. The New York Times did not count sales in religious bookshops. If they had, the bestselling book would have been Francis Schaeffer’s A Christian Manifesto, which had sold at least twice as many copies as Fonda’s book.

This volume was adopted as “a call to arms” by the Moral Majority. Its author was a leading Christian right ideologist who is often credited with identifying “secular humanism” as the new enemy of Christian America replacing communism, and with arguing that opposition to abortion should be a central concern of the movement.

The author of 23 books, many of them bestsellers that were taught in Christian schools and universities and in church study groups, Schaeffer is virtually unknown outside of the evangelical subculture. Any discussion of the Christian right necessarily has to go at least some way towards investigating both its dimensions as a cultural phenomenon as well as its peculiar character. [IDN-InDepthNews – 21 February 2020]

* John Newsinger is a member of Brighton Socialist Workers Party (SWP). His most recent book is Hope Lies in the Proles: George Orwell and the Left (Pluto, 2018).

Photo: Fundamentalist Jerry Falwell, founder of the Moral Majority, a political-action organisation to mobilise religious conservatives, with President Ronald Reagan. Credit: Salon.com

IDN is flagship agency of the International Press Syndicate.

facebook.com/IDN.GoingDeeper – twitter.com/InDepthNews