By Kul Chandra Gautam

The writer is a former UN Assistant Secretary-General and Deputy Executive Director of UNICEF.

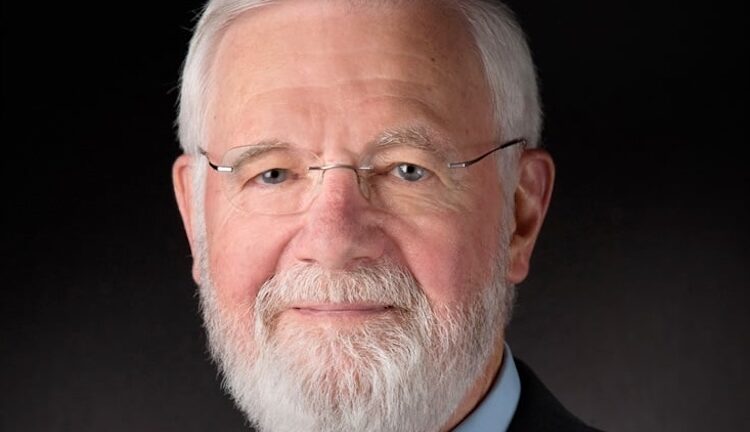

KATHMANDU, Nepal | 30 January 2026 (IDN) — This weekend, the world lost a true giant of global public health. Tributes are pouring in from public health scholars and leaders around the world, mourning the passing of Dr. William (Bill) Foege, a pioneer of the vaccination strategies that helped eradicate smallpox. This highly contagious, often disfiguring, and deadly disease killed an estimated 300 million people in the 20th century alone. The global eradication of smallpox stands among humanity’s greatest public health triumphs.

In a sad coincidence, his passing came shortly after the United States announced its withdrawal from the World Health Organization (WHO), a decision that deeply distressed Dr. Foege, as it did most of the world’s leading public health experts and institutions.

Dr. Foege was a champion of equity in health and a visionary who recognized that investing in health is an investment in the future of societies. He once said, “The slavery of today is poverty, and every one of us in this audience is a plantation owner,” reminding affluent audiences that they benefit daily from the labor of low‑wage farmers and workers across the globe. Equity and kindness, he believed, were the ultimate markers of human civilization.

A brilliant scientist, Dr. Foege was also a tireless advocate for making the benefits of modern medicine available to all in an equitable manner. But he placed particular emphasis on prevention and behavior change, arguing that many of the world’s health problems and premature deaths could be avoided at relatively low cost.

As early as the 1980s, he argued that it would cost more than US$10 billion annually to add a single year to the life expectancy of the average American male through medical interventions. By contrast, one could add up to 11 years to life expectancy through four virtually cost-free actions: (a) stop smoking, (b) moderate alcohol consumption, (c) change certain dietary habits, and (d) engage in regular moderate exercise.

To these, one could add other low‑cost behavioral changes – especially relevant in developing countries – such as exclusive breastfeeding, handwashing, safer sexual practices, and the prevention of drowning and avoidable accidents and injuries. None of these require sophisticated medical technology, highly trained manpower or vast financial investments.

Foege’s Collaboration with Jimmy Carter

Dr. Foege’s reputation as an outstanding scientist and inspirational public health leader – and his ability to present complex ideas in a simple, compelling manner – brought him into close partnership with former US President Jimmy Carter, himself a champion of global public health. President Carter first appointed him as Director of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and later as Executive Director of the Carter Center.

The Carter Center’s motto – “Waging Peace. Fighting Disease. Building Hope.” – perfectly captured the shared vision of Carter and Foege. Preventing disease, promoting equity, and helping the world’s most vulnerable communities became central to the Carter Center’s mission, with a particular focus on neglected tropical diseases afflicting the poorest populations, particularly in Africa.

Building on his pivotal role in the eradication of smallpox, Dr. Foege helped the Carter Center design the eradication campaign for dracunculiasis, or Guinea worm disease, a painful and debilitating affliction that once affected millions in Africa. Thanks in part to Carter’s leadership and Foege’s guidance, Guinea worm disease is now poised to become the second human disease in history to be eradicated.

President Carter once remarked that, besides his father, Bill Foege was one of the two most influential men in his life – someone who had saved millions of lives and improved the overall health of the planet. In Carter’s words, “Bill Foege was a pre‑eminent public health practitioner who dedicated his life to what he called science in the service of humanity.”

Foege’s Partnership with Bill Gates

Bill Gates’ interest in global health was reportedly sparked by reading the World Bank’s 1993 World Development Report: Investing in Health, which Dr. Foege had recommended to him. Gates was shocked by the scale of death, disability, and human suffering caused by readily preventable diseases, but inspired by Foege’s conviction that existing tools – especially vaccination – could dramatically improve global health.

Concluding that it would be unconscionable to wait until his retirement to act, Gates decided to leave his role as CEO of Microsoft and pivot toward global health philanthropy, establishing the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in 2000. He enlisted Dr. Foege as his senior advisor and mentor. More than anyone else, it was Foege who persuaded Gates to devote the rest of his life and fortune to child survival and global health, particularly immunization, through the Gates Foundation and GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance.

Since its inception, GAVI has helped vaccinate more than one billion children in the world’s poorest countries, preventing an estimated 17 million deaths. Global child deaths have declined from over 10 million annually to under 5 million. While many actors, including governments, UN agencies, NGOs, and private philanthropies, contributed to these achievements, a significant share of the credit belongs to Bill Gates – and to Bill Foege as his mentor.

In honor of Dr. Foege’s pioneering leadership, the Gates Foundation invested $50 million to build the William H. Foege Genome Sciences and Bioengineering Center at his alma mater, the University of Washington in Seattle. As Gates Foundation CEO Mark Suzman observed: “Bill was a pioneer whose work helped eradicate smallpox and accelerate childhood immunization. But what set him apart was not only his scientific brilliance; it was his belief that public health is, at its core, an expression of human kindness.”

Bill Foege and UNICEF

Bill Foege was a close friend and intellectual partner of the late UNICEF Executive Director James P. Grant. Both were visionary leaders committed to a bold agenda for child survival and development.

Grant argued passionately that it was unconscionable that 40,000 children a day -15 million annually – died in the early 1980s when low-cost, effective interventions were available to prevent such deaths. He launched a Child Survival and Development Revolution (CSDR), centered on four key interventions: growth monitoring, oral rehydration therapy, breastfeeding, and immunization (GOBI).

Initially, Grant’s ambitious goals for child survival were considered overly idealistic and even naïve. Some of UNICEF’s European Board members accused Grant of being a “Mad American” with missionary zeal and overblown ambition. The World Health Organization criticized Grant’s approach as proposing a few quick fixes of “vertical” and “technical” interventions to reduce child mortality and morbidity that were likely to detract from the pursuit of a more holistic primary health care approach.

To Grant’s rescue came Bill Foege. At Grant’s request, he agreed to head the Task Force for Child Survival, bringing together WHO, UNICEF, UNDP, the World Bank, and the Rockefeller Foundation. His impeccable credentials as a global health hero, and his eloquent advocacy, helped convince WHO, the US Congress, and European governments to support the UNICEF-led child survival agenda.

The results were spectacular: child immunization rates in developing countries rose from about 15 percent in 1980 to nearly 80 percent by 1990; deaths from diarrheal diseases plummeted; and millions of children’s lives were saved and their health improved, leading to a virtuous cycle of improved health, better education, and poverty reduction.

Building on the success of these child survival interventions, UNICEF convened the largest gathering of world leaders in history until that time at the World Summit for Children (WSC) in 1990. The WSC gave momentum to the ratification of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and adopted a broader set of ambitious goals for maternal and child health, nutrition, education, and child protection to be achieved by the year 2000. These goals became the precursors of the Millennium Development Goals.

Saga of Foege’s Candidacy to Head UNICEF

Given this history and legacy, Dr. Foege was widely seen as a natural candidate to succeed Jim Grant as head of UNICEF. However, in a twist of US domestic politics and UN diplomatic maneuvering, Foege’s candidacy became contested.

Historically, it was informally understood that the head of UNICEF was a position the UN Secretary-General would normally fill with a nominee of the US government, by far UNICEF’s largest donor in its early decades. With his impeccable credentials and strong support from US President Bill Clinton, it was widely assumed that Foege would be appointed.

Unfortunately, Foege’s candidacy became entangled in broader political tensions as UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali’s own bid for a second term had fallen out of favor with the US government. In an atmosphere of growing acrimony, Boutros-Ghali – who had a tense relationship with US Ambassador to the UN Madeleine Albright – declined to appoint Foege and instead asked the US to submit additional candidates, including women, ostensibly to placate some European governments that had nominated three candidates, including two women. The Europeans also resented the perceived US monopoly over leadership posts in UN agencies, including UNICEF.

Although the most distinguished European candidate was Dr. Richard Jolly, a highly respected British development economist and deputy to Jim Grant, the lack of European unity and overwhelming US pressure led Boutros-Ghali to appoint a compromise American candidate, Ms. Carol Bellamy, who became the first woman to head UNICEF.

The dramatic saga surrounding Foege’s candidacy – and the US decision to veto Boutros-Ghali’s own reappointment – is described in vivid detail in Boutros-Ghali’s memoir, Unvanquished: A US–UN Saga (1999).

Dismayed by Distorted Health Policies

Towards the end of his life, Dr. Foege was deeply dismayed by the distorted health policies and priorities of the current US government.

As a distinguished national and global leader in public health who served as Director of CDC during the presidencies of Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, Dr. Foege was outraged by the politicization and weakening of the CDC, NIH, and other premier public health institutions during the Trump administration. Like most of his predecessors and successors at CDC, Foege was very critical of the US Secretary of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. As a strong believer in and powerful advocate of immunization as the most potent weapon against vaccine-preventable diseases, Foege was dismayed by Kennedy’s misleading position on childhood vaccines, based on flimsy and fringe research findings.

He was equally disheartened by the US withdrawal from WHO and the defunding of other important UN agencies. Speaking of WHO, whose leadership was vital in the eradication of smallpox – as well as in the control and elimination of many other deadly and debilitating diseases – Dr. Foege remarked: “We save more money in this country each year because of the eradication of smallpox than our dues to WHO.” And yet, in a highly exaggerated and crude critique of “the so-called World Health Organization,” the US government chastised WHO for being politicized, inefficient, and harmful to US national interests.

In August 2025, Foege wrote a powerful opinion piece in STAT News, entitled How Public Health Can Fight Back in a Time of Dangerous Nonsense. In it, he wrote: “Kennedy’s words can be as lethal as the smallpox virus. Americans deserve better.”

A Humanistic Philosopher

The son of a Lutheran minister in Iowa, Bill Foege was deeply inspired by his childhood hero, the legendary German-French polymath, theologian, philosopher, and physician Albert Schweitzer’s medical missionary work in Africa. His experiences with the Peace Corps in India and as a medical missionary in Nigeria deepened his interest in issues of poverty and strengthened his lifelong commitment to global health equity.

A voracious reader and captivating storyteller, Dr. Foege was deeply versed not only in modern medical science but also in ancient and medieval Greek, Roman, Chinese, and Hindu-Buddhist philosophy. He drew on thinkers ranging from Plato, Hippocrates, and Confucius to Buddha and Gandhi, relating their teachings to modern-day public health and medical practices.

He often referred to Gandhi’s idea of the Golden Rule – that he should not be able to enjoy what is denied to others, including education, health care, and financial security. Referring to the inequities of the US health care system, he asked: “Can you imagine what health care would look like in this country if Congress were obligated to receive health care no better than the average?”

Foege believed that the ultimate measure of civilization was how societies treat their most vulnerable members. He often quoted the Quaker leader William Penn’s observation that “Healing the world is true religion.”

One of Foege’s most memorable messages to students and faculty at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health, where he was a professor, was his call for them to “be good ancestors.” “Remember that the children of the future have given you their proxy and they are asking desperately for you to make good decisions,” he said. “Because each of us can do so little, it’s important that we do our part.”

For a man who received dozens of honorary doctorates and numerous prestigious awards – including the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama in 2012 – Bill Foege remained profoundly humble.

A Personal Tribute

Personally, I regarded Bill Foege as one of my most revered mentors, alongside Jim Grant and a few other illustrious gurus. It was a true privilege to collaborate with him during my career at UNICEF. Even after my retirement, I corresponded occasionally with him, seeking his guidance and commiserating about how our cherished UNICEF had lost some of its luster in the post-Grant era, and about the serious undermining of the good work of CDC and WHO by the Trump administration.

Like so many others, I was inspired by his wisdom, optimism, and moral clarity. At 6 feet 7 inches, Bill Foege was literally and figuratively a towering figure. Yet his grace and humility ensured that none of his mentees—including me, at a diminutive 5 feet—ever felt small. Like Jim Grant, he always found ways to bring out the best in people, uplift their spirits, and motivate them to serve humanity to the fullest.

I have often felt that Bill Foege fully merited a Nobel Prize, either on his own or jointly with Bill Gates, for their monumental contributions to saving lives and advancing global public health. His legacy will live on through the institutions he strengthened, the partnerships he forged, and the countless students, health professionals, and development workers he inspired.

Few individuals have contributed more to humanity. Bill Foege’s life remains a powerful testament to science in the service of humanity. [IDN-InDepthNews]