By Jonathan Power*

LUND, Sweden | 20 January 2026 (IDN) — Danish soldiers arrived in Greenland. Sweden sent fighter jets to nearby Iceland. France was waving a stick, promising worse to come. It appeared that some European countries were preparing for the possibility of armed clashes in the event of a United States invasion.

But what, precisely, should be done if President Donald Trump orders his military in, calculating that Europe needs America so much that it will ultimately back down?

Right is on Europe’s side. Military strength is not. And if Europeans and Greenlanders attempt to fight back militarily, Greenland’s small population of just 55,000 could end up dead or seriously injured. The human cost would be catastrophic and irreversible.

Europe, therefore, needs to consider an alternative strategy—one that defends sovereignty and democratic values without turning Greenland into a battlefield.

Perhaps Europe should seriously consider nonviolent resistance as an alternative.

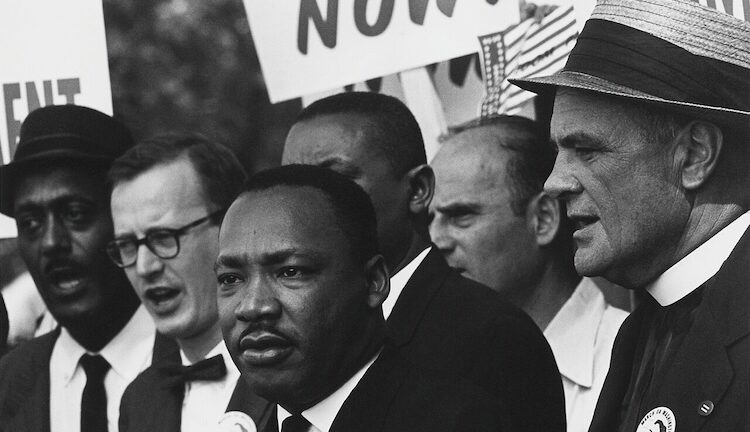

Violence begets violence. As Martin Luther King once said, “The means and the ends must cohere. We will never have peace in the world until men everywhere recognise that ends are not cut off from means… You can’t reach good ends through evil means.”

The empirical case for non-violence is strong. According to Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan, writing in Foreign Affairs, nonviolent resistance campaigns between 1900 and 2006 were twice as likely to succeed as violent ones. They were also more likely to lead to peace and democratic rule—even in highly authoritarian states.

When only about 5 per cent of the U.S. electorate supports Trump’s move against Greenland and Denmark, might not an invasion—especially one met with visible, peaceful resistance—trigger impeachment proceedings in Congress?

History suggests this is not an idle question.

Lessons from history: how regimes fall

Practitioners of non-violence need to have no false modesty. Chenoweth and Stephan’s research shows that even when governments violently repress nonviolent movements, such campaigns still succeed almost half the time. By contrast, only about 20 per cent of violent movements achieve their aims—mainly because they fail to mobilise mass support or elicit elite defections.

Even failed nonviolent movements matter. Countries that experienced failed nonviolent campaigns were still four times more likely to become democracies than those where resistance turned violent from the outset.

Critics rightly point to failures: Tiananmen Square in 1989; the Arab Spring, hijacked by extremists or undermined by poor leadership; Ukraine, where legitimate protest was compromised by the infiltration of extreme right-wing groups, provoking Russian intervention. These criticisms are valid.

But violence, too, has repeatedly failed—whether in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, or eastern Ukraine. The difference is that non-violence, even when it does not succeed, dramatically reduces the number of innocent people killed or wounded.

Civil resistance does not succeed because it softens dictators’ hearts. It succeeds because it attracts broader participation and imposes unsustainable political and economic costs on those in power.

From civil rights to Greenland

The last Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, easily crushed armed opposition in the 1960s and 1970s. But when oil workers, bazaar merchants, and students launched mass nonviolent resistance—strikes, boycotts, and protests—the economy faltered, repression overstretched the state, and even the United States withdrew support. The Shah fled.

The two most critical nonviolent movements of our era tell the same story.

In the United States, Black Americans—beaten and brutalised by racist police—won over public opinion through disciplined non-violence. Congress changed course. Segregation fell. Voting rights followed.

In Poland, 16,000 shipyard workers went on strike in Gdańsk in 1980. That strike was only the visible tip of a decade-long campaign. The trade union Solidarity grew into a mass civil resistance movement of 10 million people. Strikes, underground newspapers, cultural resistance, and the quiet moral authority of Pope John Paul II gradually undermined communist rule. Violence was minimal. By 1989, semi-free elections were held; by 1990, Lech Walesa was president.

Communism in Eastern Europe collapsed not by guns, but by legitimacy draining away.

We need to rethink how to defend liberty in Greenland. Guns will not do the trick.

What is required is the iron fist—but inside a velvet glove. Greenlanders, Danes, and other Europeans should stand in front of any invading forces, link arms, and dare U.S. soldiers—many of whom will harbour private doubts—to shoot unarmed civilians.

They won’t.

That is how democracies defend themselves when brute force threatens to overwhelm the rule of law. [IDN-InDepthNews]

Note for editor:

Jonathan Power was a member of Martin Luther King Jr.’s staff. For 17 years, he was a foreign affairs columnist for the International Herald Tribune (now The New York Times) and is the author of nine books on foreign affairs. Website: jonathanpowerjournalist.com

Copyright: Jonathan Power