By Ambassador Dr Palitha Kohona

The writer is Sri Lanka’s Former Ambassador to China, a former Permanent Representative to the UN, a former Foreign Secretary, and a former Head of the UN Treaty Section. The following is extracted from a presentation De Kohona made to the Colombo Port City Rotary Club.

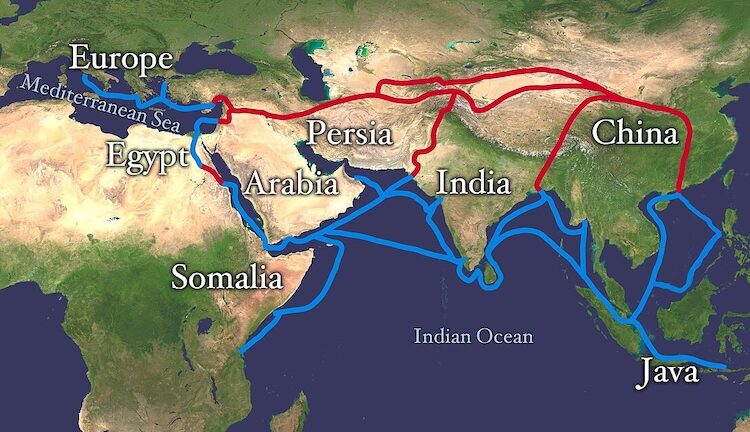

COLOMBO | 1 November 2025 (IDN) — Sitting in the middle of the Indian Ocean at the southern tip of India and the meeting point of two monsoon winds and swirling ocean currents, Sri Lanka (Lanka, Zeilan, Ceylon, Serendib, Senjialoguo, etc., in the past) occupies an enviable strategic geographical position. A blessing that, with careful and judicious management and long term vision, can be leveraged to its advantage, which it has done effectively in the centuries gone by and, mismanaged, a curse that has and will attract the rapacious attentions of global and regional predators seeking to exploit the island’s precious products (in the past, precious gems, cinnamon, pepper, war elephants, ivory, etc.) and its incomparable location, to dominate the Indian Ocean.

Throughout history, Lanka has attracted a multitude of sailors of different friendly and marauding navel powers, tradersseeking Lanka’s own exotic products or seeking to exchange the products from their countries for those from distant lands in the far East or far west, holy men, especially Buddhist monks from the east searching for the sublime Dhamma for which Lanka was reputed, simple adventurers, and empire builders for whom this island was a challenging but worthy prize.

From the East, the Chinese and those from the Malay region arrived in their various vessels throughout the centuries, and from the early days, they used Lanka as a lucrative central link in their trading ventures along the southern Silk Route. They were not empire builders. Archaeology and contemporary writings suggest that hundreds, perhaps thousands, of their ships visited Lanka, which became a significant hub for trade on the Maritime Silk Route. At times, we elegantly parried and greatly benefited from the attention our location brought us, especially in trade. Our impressive ancient cities and massive archaeological sites reflect the wealth that resulted. Sometimes we faltered. Today, with East-West rivalries intensifying, we must learn from history and avoid repeating the mistakes that have caused so much national grief.

Historical, Religious and Trading Relations

A brief look into history is warranted at this point to understand the complexities of the Maritime Silk Road’s impact on Sri Lanka and beyond. Historically, records suggest that a multitude of traders, holy men and casual visitors were attracted to Sri Lanka. Casual visitors were drawn by tales of this splendiferous island from sea farers and its breathtaking attractions, some no doubt exaggerated, Buddhist monks were attracted to Lanka, primarily from distant China and South East Asia, with the island’s reputation for being the repository of the purest form of Buddhism especially after the decline of Buddhism in India and traders from many nations came here to meet others of their kind from across the known world and goods, ideas and culture were exchanged. The country attracted waves of these different groups over the centuries, from far afield as ancient Rome and Greece on one side, Persia and the Indian subcontinent on the other, not to mention rapacious invaders. They all travelled by sea, which was and remains the highway of trade and ideas, in dhows from the West and in large Chinese and east Asian junks from the East.

Tales Reflected in Ancient Maps

Many left written records of their impressions of the island. Others carried their impressions to their homelands. Judging by the maps drawn by cartographers in distant lands, most of whom had not visited the island but had heard of it from travellers, the island enjoyed an exaggerated reputation.

Eratosthenes (276–194 BCE) created a world map, incorporating information from Alexander the Great’s campaigns and those of his successors. Lanka is depicted in it, but its size is grossly exaggerated. Pomponius is unique among ancient geographers in that, after dividing the Earth into five zones, of which only two were habitable, he asserted the existence of antichthones, people inhabiting the southern temperate zone, which was inaccessible to the folk of the northern temperate regions due to the unbearable heat of the intervening torrid belt.

Surviving texts of Ptolemy‘s Geography, first composed around 150 AD, suggest that he continued to use Marinus’s equirectangular projection for its regional maps, while finding it inappropriate for maps of the entire known world. He clearly depicts Lanka as the island of Taprobane. The Tabula Peutingeriana (Peutinger Table) is an itinerarium that shows the road network of the Roman Empire.

It is a 13th-century copy of an original map dating from the 4th Century, covering Europe, parts of Asia (including India), and North Africa, with Lanka clearly reflected in it. The map is named after Konrad Peutinger, a German humanist and antiquarian of the 15th–16th Century. Lanka is not much exaggerated and does not compete with India in size. Around 550 AD, Cosmas Indicopleustes wrote the copiously illustrated Christian Topography, a work partly based on his personal experiences as a merchant on the Red Sea and Indian Ocean in the early 6th Century.

Though his cosmogony is refuted by modern science, he has given a historic description of India and Lanka during the 6th Century, which is invaluable to historians. Cosmas appears to have personally visited the Kingdom of Axum in modern Ethiopia and Eritrea, as well as India and Sri Lanka. Al-Idrisi created the Tabula Rogeriana in 1154 while working for the Christian King of Sicily. Al-Idrisi drew information from interviews he conducted with dozens of travellers, blending them with authoritative texts, such as Ptolemy’s. Lanka appears on his map.

Ibn Battuta, the Moor from Tangiers, who visited the island in the 14th Century, was not wrong by much when he observed that this was the most beautiful island on Earth and was only 40 leagues from paradise.

Lanka’s Links with the Middle Kingdom

Sri Lanka, like other countries in South Asia, had developed important relations, both religious and commercial, with the Middle Kingdom from the early days. The writings of scholars, soldiers, monks, travellers, and traders suggest a strong Chinese interest in Lanka from times immemorial. The earliest records indicate that the interchanges along the Maritime Silk Road began to flourish during the Han Dynasty, from 207 BC, and continued for centuries afterwards. After Zhang Qian, the envoy of Emperor Wu of Han, who was sent to the West (Central Asia) to develop relations with the kingdoms there, returned from his mission, he reported hearing of wealthy kingdoms in the Southwest beyond the seas.

Subsequently, Emperor Wu dispatched vessels from the ports of Xuwen and Hepu to the kingdoms beyond the seas. Records indicate that Lanka was one of the kingdoms visited by those ships. Later, a Roman Envoy dispatched by Emperor Aurelius arrived, using the sea route, in the court of the Chinese Emperor in 166 AD. This visit would suggest that news of the Chinese Empire had reached the court of Rome along the Silk Road as early as the 2nd Century.

The Strong Religious and Political Links with China along the Maritime Silk Road

It was not only trade that boomed along the Silk Road, but also cultural and religious exchanges, bringing lasting changes to countries and societies. Technologies, food habits, agricultural practices, and even diseases, such as the plague, crossed borders along the Silk Road.

It has been proposed that dozens of wrecks of Chinese sailing vessels lie off the coasts of Sri Lanka, suggesting a thriving seaborne trade. Professor Osmund Bopeaarachchi (Emeritus Director of Research at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) has written of these sunken vessels. Many of these wrecks and the perishable items have been eaten by sea worms and rotted away and not much remains. Some stone anchors have been found.

The recently discovered wreck at Godawaya in southern Sri Lanka suggests a bustling trade in copper, glass, iron, and ceramics. If dozens sank in bad weather, hundreds of Chinese vessels, if not thousands, are likely to have called at our ports. It was then the natural point for sailing vessels wafting before the Northeastern Monsoon winds to stop, rest, replenish their supplies, and engage in trade. William Dalrymple suggests that Chinese goods unloaded in Lanka were then transshipped to South India, which was visited by many Roman and Greek vessels.

During the Tang Dynasty, the maritime Silk Road experienced considerable growth, with Guangzhou serving as its hub. The Song and Ming dynasties oversaw a massive expansion of the Maritime Silk Route. Admiral Zheng He led large treasure fleets that definitely visited East Africa, and Gavin Menzies, in his 1421: The Year China Discovered the World, controversially but commercially successfully, suggests may have even reached the Americas.

While foreign ships came to Lanka’s shores by the hundreds, Lankan sailors also appear to have sailed to foreign ports, especially to the East, and left an imprint. A Chinese mandarin, Li Chao, reported that among the many foreign ships that arrived at An-nan and Kuang-chou, “the ships from the Lion Kingdom were the largest with stairways for loading and unloading, which are several tens of feet in height”. A plaque in the Hong Kong Maritime Museum states that the language of Macao, a Chinese port frequented by foreign sailors for centuries, has Sinhala influences.

The regular presence of Chinese in the Indian Ocean for trade is borne out by historical accounts left by many, including the Chinese monk Fa Xian (5th Century), Marco Polo (13th Century), Ibn Battuta (14th Century), ending with the expeditions of Admiral Zheng He, in the early 15th Century.

Those visitors who came, especially from China, not only left detailed observations which have been used to corroborate our own historical records in Sri Lanka, but also bits and pieces of their own cultures, enriching ours. The Chinese traders and Shaolin monks probably introduced Chinese martial arts. A term in Sinhala for the indigenous martial arts is Cheena–Adi. This is too much of a linguistic coincidence. I was treated to a stunning demonstration of Shaolin Gongfu (martial arts) by the monks during a visit to the Shaolin Temple in Dengfeng, Henan Province.

The main attraction for the majority of the Chinese appears to be the shared religion — Buddhism. In addition to the traditional Confucianism and Taoism, which commanded widespread adherence among the Chinese, they had begun to consider Buddhism to be part of their national religious tradition since the introduction of Buddhism to China in the first century AD by two monks from modern-day Afghanistan, Kasyapa Matanga and Dharmaratna, who travelled to China across the vast and inhospitable Takla Makan Desert. The emperor received them warmly and built the White Horse Temple, Baima Shi, which is the first Buddhist temple in China and is a major attraction today.

Since then, emperors, commoners and monks sought closer relations with countries to the West, especially the Indian sub-continent and Sri Lanka, to enrich their spiritual needs. Sri Lanka had a reputation, even then, for safeguarding the pristine doctrine, especially after Buddhism declined in India. Lanka was the first country to commit the Buddhist canon to writing. It happened in Alu Viharaya in 29 BC. Previously, the canon had been preserved as an oral tradition.

Chinese writings of the period suggest considerable knowledge of the island, including its politics and religion, among Chinese scholars.

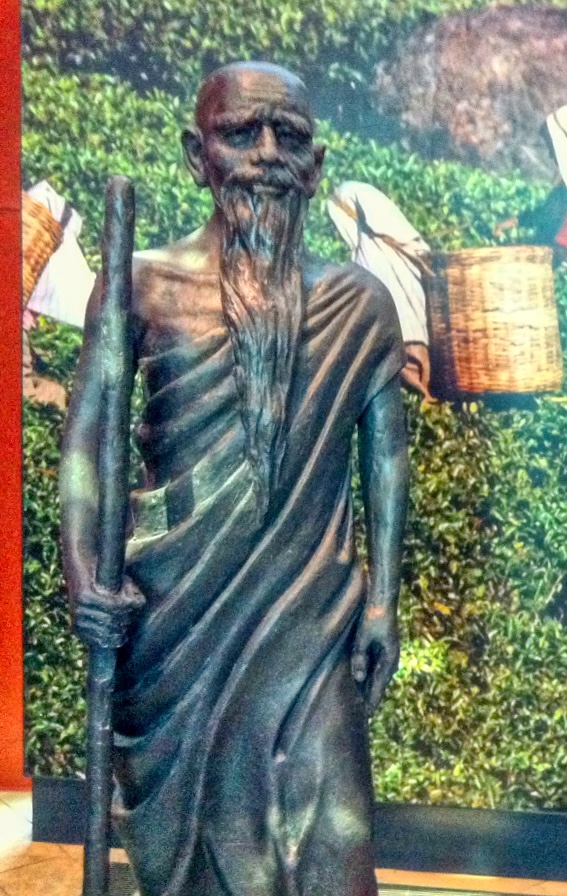

The copious writings of the fifth-century scholar monk Fa Xian, who set off on foot from Chang’an (Xian), followed the Silk Route, crossed the inhospitable Takla Makan desert, and eventually reached India on foot, where he spent 10 years. Then he boarded a ship and arrived in Lanka, where he spent several years at the Abhayagiriya Monastery in the ancient capital of Anuradhapura. His writings tell a tale of bygone prosperity and complex international diplomatic and trading relations. Fa Xian details the splendid pageant in honour of the Tooth Relic of the Buddha, which takes place to this day, but now in our last royal capital, Kandy.

Interestingly, Fa Xian decided to return to China by sea, suggesting that it was an option for anyone wishing to travel to China from Lanka. Two hundred years later, Monk Yijing undertook the journey to South Asia by sea. He considered the sea journey to be safer. Fa Xian carried a load of religious texts from Lanka and reached the port of Qingdao in 413 AD. He returned to Nanjing, which was the capital by then. This also suggests that Lanka, at the time, had a significant literary tradition. The ship was big enough to accommodate 200 passengers. Ships that big were not constructed in the West until almost the 20th Century. A Record of Buddhist Kingdoms (Fo Guo Ji 佛国记), painstakingly written by Fa Xian, serves as a notable independent record of early Buddhism in India and the wider region.

Diplomatic Links

Demonstrating the connections spawned by the maritime route, the Maritime Silk Route, four embassies were sent from Lanka to the Chinese imperial court in the fifth Century. Chinese records indicate that these embassies were sent during the reigns of King Buddhadasa, the prolific builder of public hospitals in the early 4th Century, Upatissa I, and his son and successor, Mahanama (412-434 AD). The Lankan King, probably Mahanama, sent an embassy with a valuable Buddha statue and a replica of the Temple of the Tooth Relic in Anuradhapura to the court of Emperor Xiaowu. The Chinese document “The Biography of Bhikkunis,” written in the sixth Century, details a visit by Sinhala nuns to Nanjing to inaugurate the order of nuns in China. Nuns from Lanka established the Chinese order of nuns, and, ironically, the order of nuns survives in China, while there is no formal order of nuns in Sri Lanka anymore.

Chinese records indicate that in 456 AD, five eminent Sinhala monks visited the Emperor, and one of them was an accomplished sculptor. Undoubtedly, art and architectural exchanges followed interchanges involving the common religion. Two Buddhist texts, Karanamudra Sutta and Vimukthimagga, were translated from Sinhala to Chinese in 489 and 505. In the 8th Century, another monk, Amogha Vajra, a pupil of Vajrabodhi, travelled to Lanka and translated the Karanda Mudra Sutta into Chinese. King Aggabodhi sent him as an envoy to the Emperor’s court in 746.

Gunavarman, from the royal family of Kashmir, and Vajrabodi, who arrived on the island after sojourning in the South Indian Pallava Court. These were again two of the religious personalities who, after being enriched by their experiences in Lanka, went on to China. The fact that they boarded ships from Lankan ports is also illuminating.

While religious connections gave substance to the bilateral relationship, the trading relationship between the two countries also flourished in parallel. The Arab geographer Edrisi details the extent of Lanka’s international trade during the time of Parakramabahu the Great, who also sent a royal princess to the court of the Yuan Emperor. The trade between China and Lanka flourished during this period, and Chinese vessels brought silk, porcelain, aloes, and sandalwood to our ports. Even in recent digs at Polonnaruwa, Lanka’s medieval capital, ceramic pieces and Chinese coins have been discovered. Lankan exports included gems, spices, filigreed gold, pearls, ivory, textiles, and other items, some of which were likely carried in vessels built in the country. Traders from the western lands exchanged their products for the Chinese goods in Sri Lankan ports and the Lankan kings likely reaped a bountiful benefit in taxes and duties.

The great Kublai Khan, having heard tales of the large number of Buddhist relics held in Lanka, dispatched an envoy in 1282 to Lanka, requesting the alms bowl of the Buddha, venerated by the Sinhala people. However, the Lankan King refused this request. The Venetian merchant and explorer Marco Polo served as a foreign emissary for Kublai Khan. As part of his service, he was sent on diplomatic missions throughout Southeast Asia, which included a visit to Lanka. Interestingly, these missions were undertaken by sea. In 1291, Kublai Khan charged Marco Polo and his family with their final duty before returning to Europe: escorting the Mongol princess Kököchin by sea to Persia. Their journey took them from the port of Quanzhou, past Sri Lanka, and on to Persia. His famous book, The Travels of Marco Polo, includes a description of the island, which he called “the finest island of its size in all the world” and a land rich in gems and spices.

By the second quarter of the 6th century, Sri Lanka had clearly emerged as the centre of sea trade between the West and the Far East. Chinese vessels, and ships from other lands of the Far East, came into the ports of Lanka, conveying their cargoes of silk, especially.

Meanwhile, from the West came vessels and the merchandise of the Persians and the Axumites, including wine, glass, and similar goods. In the ports of Lanka, mariners from distant lands, as well as merchants from India and the East, exchanged their goods and purchased the products of Lanka. The Christian Topography of Cosmos Indicopleustes, written around this time, provides a lengthy description of Lanka, which he referred to as the Island of Taprobane.

Because of its central position, Lanka had developed into a great emporium, receiving wares from all the trading markets and in turn distributing them throughout the then-known world. Lanka was indeed a mercantile exchange and a busy port of call for ships from the ports of India, Persia, Ethiopia and from China in the distant Far East. By the middle of the seventh Century, the Arabians had begun to dominate the ocean routes to the West and handled all that trade, but the Chinese continued to retain control of the seaborne traffic to the Far East.

Some of the principal works available in China with references to Lanka, are ‘The Itinerary of Ke Nee’s Travels in the Western Regions” (X century), a “General Account of the Island Foreigners” by Wang Ta-Yuani (Fifteenth Century, “Description of the Western Countries” of the fourteenth Century, “Foreign Geography” and “A History of Foreign Nations”.

Two Chinese works deal with the campaigns of Cheng He, the eunuch sent to Sri Lanka by the Ming Emperor, entitled “Description of the Star Raft” by Fei Hsin, who himself was with the expedition, and “Description of the coasts of the Ocean” by Ma Huan, a Chinese Muslim who was attached to the expeditions as an interpreter. Another critical and similar type of work was compiled by Chau-Ju-Kua, a Chinese inspector of foreign trade, which sheds light on the trade of the Asian regions.

The lion sculptures at Yapauwa are heavily influenced by Chinese art. There is no doubt that Chinese sculptors and architects worked in Lanka. The troves of Chinese coins and porcelain being recovered from various parts of the country suggest a thriving trade.

Admiral Zheng He’s repeated visits and his involvement in the replacement of the Lankan King with Parakramabahu VI, who was later ousted by Parakramabahu VII, in the early 15th Century, are well recorded. Descendants of the Sinhala prince taken to China have been traced in Quanzhou. Mrs Xushi claims to be a 19th-generation descendant of the prince. Parakramabahu VII sent six missions to the Ming court.

Cheng He left a pillar inscription marking his second visit to the port of Galle in 1409. Today, it can be seen at the Galle Museum. Chinese writings do not agree on the purpose of Cheng He’s interventions in Sri Lanka.

Some writings suggest that he sought to ensure the King’s adherence to the correct teachings of the Buddha, while other writings indicate that he sought to take the Tooth Relic to China. Cheng He, on a subsequent visit, made an offering at the shrine of God Upulvan in Dondra. The Portuguese later destroyed this magnificent shrine.

Belt and Road Initiative

Before I conclude, I would like to touch briefly on China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

President Xi Jinping’s One Belt One Road (now known as the Belt and Road Initiative, BRI) initiative, unveiled in 2013, has presented countries in the broader region with both a new challenge and a unique opportunity to accelerate their economic development. An investment bonanza is being made available under the BRI, especially for the countries along the ancient Maritime Silk Road.

Coupled with the investment-driven BRI, China has also begun to subtly emphasise its cultural and religious links in the wider region. A soft power caress of the area! According to Ian Johnson, author of The Souls of China, President Xi Jinping has embraced religious faith as part of his “Chinese Dream” and the “Belt and Road Initiative”. The atheist Chinese Communist Party has now recognised that religion in Chinese history was a powerful tool in domestic governance and international diplomacy. For Xi’s “rejuvenation” of the Chinese nation and national culture after the “century of humiliation”, this mix of faith and politics constitutes a “re-imagining of the political-religious state that once ruled China”.

When Xi Jinping’s father, Xi Zhongxun, was head of the party’s religious work, beginning in 1980, China’s Central Committee issued the famous Document 19, warning party members against banning religious pursuits, as it would isolate the Chinese people. Ever since, China has been restoring places of worship that were damaged during the Cultural Revolution and in previous periods of internal strife and external invasion.

I have visited many historical sites that have been impressively conserved and renovated. These sites attract vast crowds today. This development also creates a comfort level among the countries of the Indian Ocean region, which, while sharing a broadly similar religious tradition with China, also have feared the secular robustness of the Communist Party that rules China.

The BRI intends to make available a stunning $4– $ 8 trillion. While the Marshall Plan achieved considerable success, the BRI funds are expected to achieve substantially more by creating a vast region of shared prosperity that stretches from Africa to East Asia, with a clear beneficiary being a large number of developing countries.

Adding strength to the BRI, the Chinese Yuan has now been recognised as a reserve currency by the IMF and China appears to be increasingly moving towards international payments in Yuan. Talk of de-dollarisation is frequent these days. The Yuan joins the US Dollar, the Euro, the Yen, and the British Pound in the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDR) basket, which determines the currencies that countries can receive as part of IMF loans.

Coupled with the strength of the Chinese economy, Chinese technology has advanced spectacularly. China has 700 million internet users, and web development has become a cottage industry. It has become the biggest e-commerce market in the world. Over half of the world’s most valuable companies are now based in China. China, which initiated the electronic bike exchange, has made rapid progress with electronic payments. Other countries are simply playing catch-up. Baidu is the largest search engine, and China’s Alibaba is bigger than Amazon and eBay combined. DeepSeek is an open-source Chinese search engine and is now rivalling ChatGPT and other Western options. China’s BeiDou navigation system is rivalling or surpassing its Western equivalents. Tempted by the vast Chinese market, Google is hankering to return to China. Much has been written about the massive progress made by China in the transportation industry, with over 43,000 km of high-speed train tracks already in use as of 2023, and its Fuxing Hao trains delivering over 2.3 billion passengers. China is the largest global market for motorcars, with production reaching 23.7 million units in 2017, surpassing that of the US and Japan combined. China has emerged as the world’s largest producer of electric cars, with BYD now dominating global markets. China’s construction industry has also climbed dizzying peaks, with some city skylines looking as if they were plucked out of science fiction movies. China is also making massive investments in biotechnology, surpassing those of the US.

Despite muted reservations and orchestrated criticisms of the BRI, primarily regarding the Chinese debt trap, countries in the region, especially those in Africa, are already reaping substantial benefits from China’s investments. Economists, including those at the World Bank, agree that significant Chinese investments have largely driven the recent rapid upward movement of the economies of several African countries. [IDN-InDepthNews]

Image: Extent of Silk Route/Silk Road. Red is the land route, and the blue is the sea/water route. Source: Wikimedia Commons