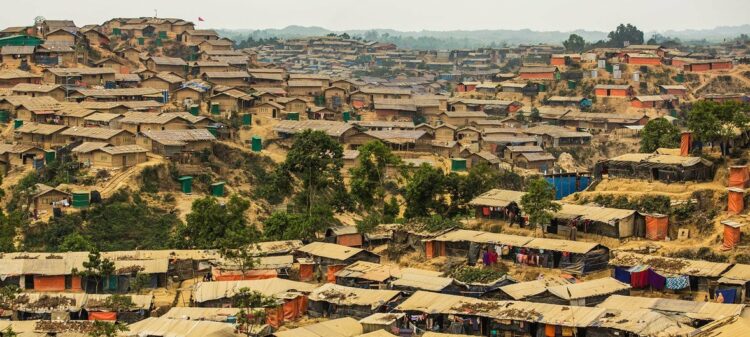

In a crisis, data is not just numbers; it can save lives. It helps people plan ahead, respond faster, and make sure aid reaches those who need it most. But in places like the Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh, where data systems are fragmented or controlled by a few powerful actors, they can make things harder instead of helping.

At a recent conference on Solid, FAIR, and technologies in Linked Web, researchers Nandini Jiva, Poorvi Yerrapureddy, Rohan Pai, and Soujanya Sridharan from the Aapti Institute shared a case study that illustrated this clearly. It focused on the Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, which explored how digital systems shape coordination, access, and power in crisis settings.

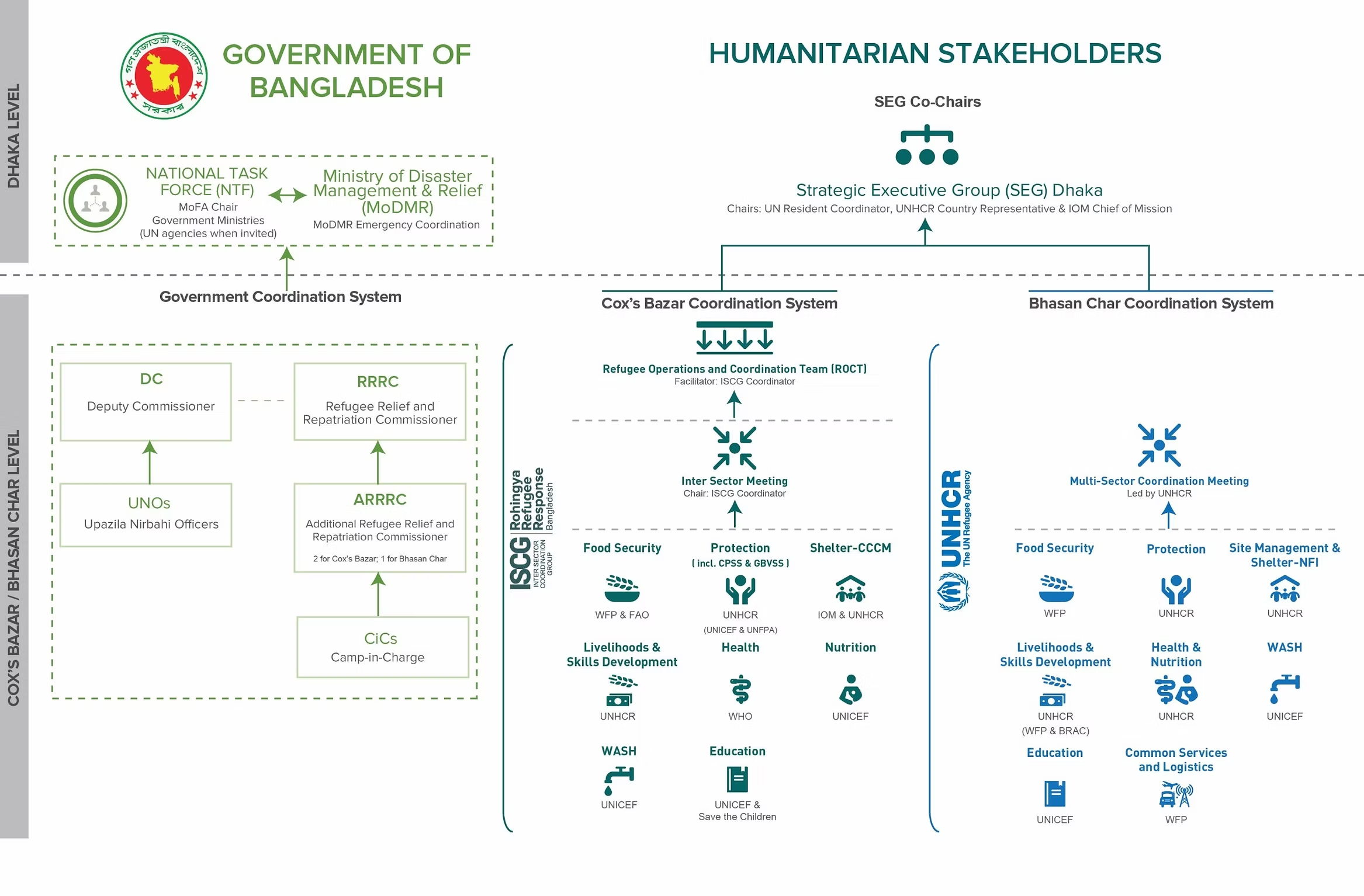

Drawing from field research, the Aapti team described how the camp coordination system was established through a multi-stakeholder coalition, involving the Government of Bangladesh, UN agencies such as the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and various sectors of service delivery, including food security, education, and gender-based violence.

A single digital ID system, with unequal access

In the camps, refugees use a UNHCR Smart Card, a biometric digital ID that gives access to essential services like food and healthcare. Initially, families had multiple cards for different services. Over time, this was streamlined into a consolidated digital ID, interoperating across several humanitarian systems like UNHCR’s PRIMES (Population Registration and Identity Management Ecosystem), WHO’s District Health Information Software (DHIS2), and WFP’s beneficiary information and transfer management platform called SCOPE.

From a technical standpoint, this interoperability sounds like a success. It streamlines access to services and helps organizations coordinate their work. But in practice, the system is very centralized and often excludes key actors. Due to their scale and political capacity, international organizations became the first responders in any crisis. Local NGOs, despite having deeper community knowledge, are being sidelined. They do not have access to the data, even though it is technologically interoperable.

The researchers found that local actors were often excluded from key decision-making and system design. This exclusion is not due to technical limitations, but the political dynamics of the refugee camps are shaped by the government’s desire for control.

When control is concentrated, people lose out

This concentration of control has real consequences. When only a handful of global actors manage the infrastructure, local organizations with valuable knowledge and trust are pushed aside. Refugees themselves have little to no voice in how their data is used or shared. As Aapti researchers put it, “These digital infrastructures don’t just reflect power, they reproduce it.” The promise of “interoperability” starts to fall apart when transparency, inclusion, and accountability are missing.

What would an inclusive rights-based digital infrastructure look like?

The takeaway from Aapti’s case study is clear: making systems technically interoperable is not enough. What is needed is governance that supports inclusion, equity, and trust. Aapti offered several recommendations:

- Homogenize data infrastructure across platforms, such as PRIMES, DHIS2, and SCOPE, to enable smoother and more open data flows.

- Include community actors in data collection and decision-making, especially through models like Accountability to Affected Persons (AAP), which support things like grievance redress and community surveys.

- Use open-source tools certified as Digital Public Goods (DPGs). These are designed with privacy and public interest in mind and could help balance the playing field.

Interoperability needs inclusion

The case of Cox’s Bazar shows that data systems are not neutral. They are shaped by power, and they shape power in return. Building fairer, more resilient humanitarian responses means treating interoperability not just as a technical issue, but as a question of who gets a seat at the table. Or as Aapti’s team puts it: “You can build any sort of tech platform, but if the local actors cannot access them, and if political dynamics prevent shared governance, the promise of digital coordination collapses.”