By Jonathan Power

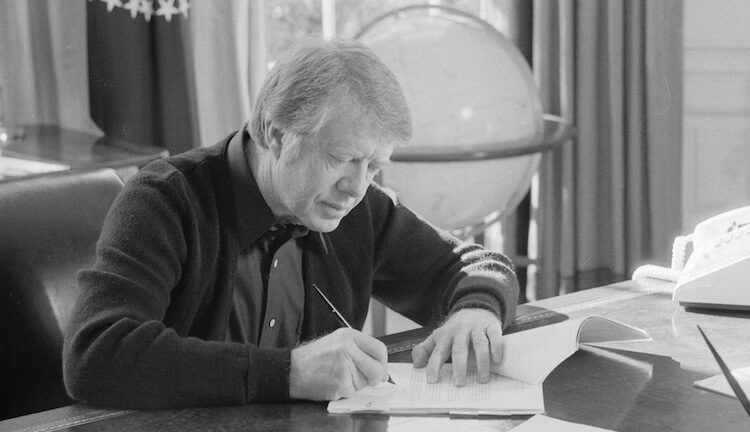

LUND, Sweden | 18 February 2026 (IDN) — Jimmy Carter liked to think of himself as a human rights president. Many of us believed he heralded a new spring.

Spring is coming again now. Snowdrops and crocuses are pushing through the frost; daffodils are preparing to bloom; trees along the Potomac will soon show their first green buds. I remember cycling through Washington in the early months of Carter’s presidency, past the cherry blossoms and dogwoods along the riverbanks, filled with hope.

But one learns, again and again, that it is never spring forever.

Carter was a deeply religious man. Whenever he returned home, he taught Sunday school. He believed that God had created the United States, in part, “to set an example for the rest of the world.” Human rights would be central to that example.

In practice, it proved far less straightforward.

As Hodding Carter, the State Department spokesman at the time, once observed, Carter’s human rights policy was “ambiguous, ambivalent, and ambidextrous.” Patricia Derian, his assistant secretary for human rights, often found herself frustrated by the limited backing she received from senior officials.

Yet Carter’s policy had a real impact, especially in the Western Hemisphere.

After losing his bid for a second term, Carter visited Argentina. He was met by crowds thanking him for helping weaken the brutal military regime that had imprisoned and tortured opposition activists. The Catholic Church there had been largely silent — unlike its counterparts in Chile and Brazil, where religious leaders openly challenged repression. Carter’s intervention in these countries was unprecedented: non-violent, principled, and ultimately effective. Arms sales were halted. Economic pressure mounted. Regimes weakened and eventually fell.

Similar ripples were felt across Latin America and beyond.

In Indonesia, India, Myanmar, East Timor, Zimbabwe, and South Korea, Carter’s stance emboldened labour movements, religious leaders, and liberal reformers. When South Korea’s military regime threatened to execute opposition leader Kim Dae-jung, Carter warned that the United States would withdraw its troops. Kim lived—and later became president.

Carter’s human rights crusade also reshaped global expectations. His ambassador to the United Nations, Andy Young, pushed for sanctions against white-ruled Zimbabwe, hastening the transfer of power to the country’s Black majority. Human rights became a benchmark against which Western foreign policy would thereafter be judged.

Even when Carter faltered, the standard remained.

Power, Principle, and Compromise

Yet as Martin Ennals, then secretary-general of Amnesty International, warned me at the time, it would be impossible for Washington to sustain an untainted commitment. Human rights would inevitably become entangled with other strategic priorities—and diluted.

The most glaring inconsistencies emerged in Asia.

Carter’s obsession with countering Soviet communism skewed his sense of balance. Even in his final speech at the Democratic National Convention, he singled out the USSR as the principal human rights violator, scarcely mentioning abuses elsewhere.

When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979, Carter pivoted decisively toward China. Despite campaign promises that he would not “ass-kiss” Beijing, he ignored the jailing of Democracy Wall activists and looked the other way when the dissident Wei Jingsheng was sentenced to fifteen years in prison.

At the same time, Carter was publicly denouncing Moscow for imprisoning Anatoly (Natan) Sharansky.

The most troubling example of dual thinking — call it hypocrisy — concerned Cambodia.

After the U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam, Cambodia under Pol Pot descended into genocidal horror. An estimated 1.7 million people perished in what became known as the “Killing Fields.” In 1978, Carter declared Cambodia “the worst violator of human rights in the world.”

But little followed.

China, which Carter was courting as a counterweight to Moscow, was Pol Pot’s patron. “I encouraged the Chinese to support Pol Pot,” Carter’s national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski later told me. The old Kissinger formula of “playing the China card” against the Soviet Union prevailed.

As Jonathan Alter later wrote in Foreign Policy, it became worse. The United States supported Pol Pot’s claim to Cambodia’s seat at the United Nations. His regime’s flag flew outside the UN building. Most European nations — Sweden excepted — recognized it alongside Washington.

Many diplomats believed China would not have jeopardized normalization with the U.S. had Carter refused this support. Beijing had too much at stake.

Indeed, when Vietnam ultimately toppled Pol Pot, China did little more than protest.

The Soviet Lens and Strategic Blind Spots

Despite these contradictions, Carter’s supporters argue that his emphasis on human rights weakened the Soviet system from within.

Václav Havel, the Czech dissident playwright who later became president, said Carter inspired him even while he was in prison and undermined the “self-confidence” of the Soviet bloc. Eastern European human rights movements grew bolder.

Anatoly Dobrynin, the Soviet ambassador to Washington, later wrote in his memoirs that Carter’s policies “played a significant role” in loosening Moscow’s grip at home and in Eastern Europe. Once liberalization began, he concluded, it could not be fully controlled.

History suggests that human rights pressure, even when inconsistent, can have cumulative effects.

Yet the lesson is also sobering: strategic priorities often distort moral clarity.

A Tarnished Inheritance

After Donald Trump’s first term, Democrat Joe Biden entered office with rhetoric sharply critical of Moscow. He did not reverse the NATO expansion begun under Bill Clinton — a policy continued by George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and himself. Only George H.W. Bush and Trump resisted pushing NATO further eastward.

The steady enlargement of NATO up to Russia’s borders has been widely viewed in Moscow as a security challenge. That perception, whether one agrees with it or not, has fueled nationalist resentment among Russians who might otherwise have been more receptive to Western overtures.

None of these excuses for Russian human rights abuses. But it illustrates a broader truth: external pressure often hardens domestic attitudes.

Leaving aside the Russian question, Trump’s record on human rights has further tarnished America’s image. From harsh immigration enforcement practices to rhetorical disdain for multilateral norms, the United States no longer projects the moral authority it once claimed.

Do Iranians, for instance — or many others — see America today as John F. Kennedy’s or Ronald Reagan’s “city upon a hill”? It is difficult to argue that they do.

Carter’s legacy, then, is mixed — compromised yet consequential.

His conviction that human rights should be at the center of American foreign policy did not always withstand contact with geopolitical realities. But it altered expectations. It set a benchmark.

Under Trump, that benchmark has faded.

Yet human rights still run through the Democratic Party’s bloodstream. If a Democratic candidate returns to the White House, one might expect renewed emphasis on principle — tempered, perhaps, by lessons from Carter’s contradictions.

Spring does return, eventually.

But it is never permanent. It must be cultivated — and defended. [IDN-InDepthNews]

Copyright: Jonathan Power.