Support is real, but the most challenging political test comes later

By Ramesh Jaura

This article was first published on https://rjaura.substack.com/

BERLIN | 27 December 2025 (IDN) — Europe is taking on debt to fund its defence, building up its military, and asking people to be patient. History shows that the real political challenges often come afterwards.

Germany is Europe’s largest economy, its most populous democracy, and, even 80 years after World War II, still its most cautious military power. This prudence is not by chance. It comes from history, memory, and a political culture focused on restraint.

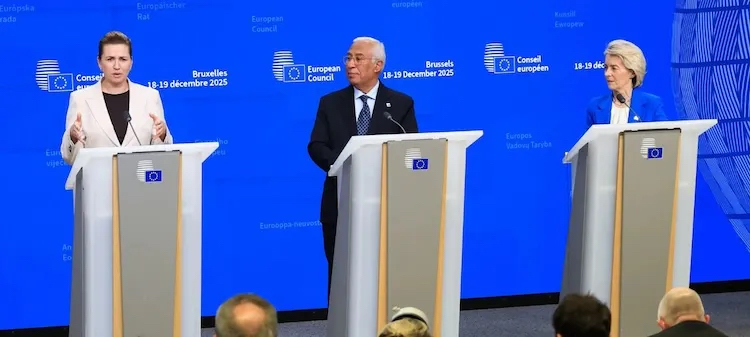

That’s why the European Union’s decision at a summit in Brussels on 18-19 December to help Ukraine meet its financial and defence needs with 90 billion euros through joint borrowing on the capital markets and backed by the EU budget—not by immediately using frozen Russian state assets, as planned earlier —is critical beyond just Kyiv and Brussels. It shows more than support for a country under attack. It signifies a greater shift, a bigger change in how Europe runs itself.

Paying for war and building up the military are no longer seen as short-term emergencies. They are becoming regular parts of European politics.

This change has not gone against public preferences. In much of Europe, including Germany, voters have agreed to higher defence spending because of Russia’s war against Ukraine. But history warns us: what people accept during times of anxiety and immediacy can become a problem later, when the costs show up slowly over many years as more debt, higher taxes, and less money for other needs.

In short, rearmament is more than tanks and missiles. It is also a test of whether people support these changes, and this will play out slowly through elections, budgets, and daily political trust. In Germany, this test will begin in earnest with the state elections in 2026. Across Europe, it will influence politics for years to come.

Why Germany Matters More Than Any Other Country

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine quickly ended that belief.

When Berlin announced a Zeitenwende, or turning point, it signified more than a change in its defence policy. It was breaking a mental barrier. The €100 billion special defence fund, the promise to meet NATO spending goals, and the new focus on military readiness collectively indicated that Germany was prepared to assume responsibilities it had long deferred.

Why is this so important? Because Germany is not just any European country. It is the EU’s economic anchor, its political centre, and more and more, the example other democracies look to for legitimacy. If Germany can balance rearmament with citizen trust in democracy, the rest of Europe might manage it too. If not, the effects will spread.

The EU’s Ukraine Funding More Than a Budget Line

Joint debt has always been a problematic issue in the European Union. It was accepted only during the COVID-19 pandemic as a one-time response to a significant crisis. By now, using this approach to war funding, Europe is quietly changing what it considers ‘exceptional.’

For Germany, this has huge effects. German taxpayers are some of the principal backers of EU borrowing. But the connection between decisions and their results is not direct. People do not vote on EU bonds. They only feel the impact later, through changes in national budgets, financial regulations, and domestic political choices.

This gap is important. Democracies depend on clear information: people accept costs when they know why they are paying and who made the decision. Rearmament and war funding make it more difficult to preserve this obviousness.

Is There Really Public Support for Rearmament?

The answer is yes, but there are important conditions.

Since 2022, support for more defence spending has grown quickly across Europe. In Poland, the Baltic states, and the Nordic countries, this support is strong and rooted in deep sentiments. Being close to Russia, remembering history, and feeling vulnerable make the need for defence feel personal.

Germany is different. There is support, but it is careful rather than excited. Many Germans accept the need for rearmament not because they believe in military strength, but because they worry about what could happen if Germany is weak. Defence is seen as insurance: costly, uncomfortable, but better than disaster.

However, this support has limits. Polls indicate that approval declines when respondents are asked how to finance rearmament. General support for defence does not always mean people are willing to accept higher taxes or long-term financial changes.

This difference is essential. Europeans primarily support security, but they are much less sure about paying for it in ways that affect their daily lives.

Borrowing as Political Strategy

Given this situation, governments have picked the easiest short-term solution: borrowing money.

Germany’s special defence fund is a good example. It enabled quick action without raising taxes immediately or cutting social spending. Similar methods are now used across Europe. Borrowing gives governments more time, sustains political agreement, and delays difficult decisions.

But borrowing also delays facing the truth.

Debt builds up quietly. Interest payments slowly increase. Defence spending stays high. Sooner or later, financial pressure becomes impossible to ignore. Then, governments must make choices they once put off, such as raising taxes, setting priorities, and deciding who should pay.

This is where history becomes instructive.

First, governments borrow extensively at the outset of rearmament. Second, taxes go up later, sometimes many years later, to equalise public finances. Third, those taxes seldom revert to their pre-crisis levels.

On average, government income stays 20 to 30 per cent higher for 15 years after a military buildup starts. Top tax rates often end up much higher than before. These changes are not temporary; they last.

Just as notable is what does not happen. Governments rarely finance rearmament by making permanent cuts to healthcare, education, or welfare. The usual idea of ‘guns versus butter’ is mostly a myth. Populations commonly choose both and pay for both by expanding the state.

The Democratic Ratchet

For democracy, these effects are quiet but vital.

Once taxes increase, they usually do not decrease. When the government grows, it rarely shrinks completely. Experts call this the ratchet effect: crises expand the state, and peace does not fully reverse the change.

People observe this as a slow change. Policies intended to be temporary become permanent. Special measures become normal. Over time, trust fades, not because leaders are behaving badly, but because what people expect and what happens diverge.

Germany’s 2026 state elections will not be only about defence policy. However, they will be the first big test of whether the new security agreement can endure after the initial shock of war.

Several questions will become critical:

· Who pays? If people think the costs of rearmament are not shared fairly, resentment will increase.

· How long? When temporary measures quietly become permanent, trust is weakened.

· Who decides? Voters want to know that decisions about security and sacrifice are made openly and democratically.

None of these issues will cause democracy to collapse. But they do create stress, according to the study.

Rearmament can go hand in hand with the renewal of democracy if leaders are honest about costs, fair about who bears the burden, and open to debate. History shows that problems come not from defence spending itself, but from how its effects are handled.

A European Challenge

Germany is not alone. Across Europe, rearmament intersects with already tense politics, including cost-of-living issues, migration debates, and rising distrust of institutions.

In some countries, security-related arguments have strengthened executive power and reduced parliamentary oversight. In others, they have led to claims that democracy is too slow or too weak to keep people safe.

The real danger is not militarisation itself. It is the slow erosion of democratic discourse, in which security is prioritised over debate, oversight, and agreement.

Rearmament Is a Long-Term Political Contract

At its heart, rearmament is an agreement between governments and citizens. Governments promise protection. Citizens assume responsibilities—financial, political, and moral—that endure far into the future.

History shows that these agreements last only when they are clear and seen as fair. When costs emerge quietly and unevenly, democracies rarely collapse suddenly. Instead, they slowly weaken, the study warns.

Europe is making decisions now that will shape its politics and finances for decades. Germany, more than any other country, will decide whether these choices strengthen or slowly weaken democracy.

Deterrence may be needed. Democratic support is not automatic. It must be renewed, not just in times of fear, but also in the long, quiet years when war feels far away, and the costs come in without much notice.

That is the real test now facing Germany and all of Europe. (IDN-InDepthNews)

Ramesh Jaura is a journalist with 60 years of experience as a freelancer, head of Inter Press Service, and founder-editor of IDN-InDepthNews. His work draws on field reporting and coverage of international conferences and events.

Original link: https://rjaura.substack.com/p/europes-rearmament-a-test-of-democracy

Related links: https://www.eurasiareview.com/26122025-europes-rearmament-a-test-of-democracy-analysis/

https://www.world-view.net/europes-rearmament-a-test-of-democracy/